Charlotte Ryan | Contributing Writer

All I ask is that if you are a Woody Allen fan, you keep in mind your favourite Woody Allen movie

What’s your favourite Woody Allen movie? This is the question that opened Dylan Farrow’s open letter in Vanity Fair published on the first of February in which she detailed the alleged sexual assault at age seven by her adoptive father Woody Allen. Her account reignited the debate regarding the allegations first released in the 1993 divorce proceedings between Allen and her adoptive mother, Mia Farrow. Allen was never prosecuted and the battle ensues. But I’m not going to write about that. This piece won’t attack or defend Allen, nor will it try to influence your opinion. With the abundance of such articles and blog posts I think it’s far more pertinent to consider whether or not we should believe an artist to be distinct from his or her work. All I ask is that if you are a Woody Allen fan, you keep in mind your favourite Woody Allen movie.

The question of art and artist is in no way a modern concern: literary theorist Roland Barthes argued in his essay “Death of the Author” that an audience shouldn’t take into account the personal opinions and lifestyle of an artist as art is drawn from a well of cultural concepts rather than one person’s experience. That’s what makes great art great: universality. As an English student, I’m inclined to agree: we can never know exactly what an author intended to write about or what exactly their personal beliefs were at any one time and that is what makes this all so fun… depending on your idea of fun.

Whether a conscious decision or not, in creating something artists draw first and foremost on the closest resource at hand: themselves

However, it cannot be denied works of art are influenced by artists’ mindsets, their value systems, their ideas of what justifies creating a novel or a poem or a film. These people felt so passionately about a topic that they put it at the core of their artistic endeavour. Or maybe not. Maybe they didn’t even think about it yet still it weaves through the art. Whether a conscious decision or not, in creating something artists draw first and foremost on the closest resource at hand: themselves.

Art in all its forms is predominated by a few recurring themes: life, death, love and power. Generations have been linked, consoled and reassured by the works of women and men living centuries before our time. We’ve been given insight into the progression of the human condition in all its glory and gore by a language of letters and images. This conversation through time is a gift and a privilege but for some it’s also an enormous responsibility. Our cultural leaders take it upon themselves to give us a shout in the dark and guide us, be it negatively or positively.

Sex sells after all and who wouldn’t want to see a balding Allen in his white Y-fronts and horn rimmed glasses pondering life, death and the female orgasm?

Here is where Woody Allen makes his cameo appearance. It’s no secret that sex features prominently in his work, granted often as a vessel for much loftier themes, but often not. Sex sells after all and who wouldn’t want to see a balding Allen in his white Y-fronts and horn rimmed glasses pondering life, death and the female orgasm? Sex is possibly the most human of all topics and worthy of discussion. This is, however, where the biography of the artist becomes problematic. As he’s never been prosecuted we must assume Allen to be innocent. But what if?

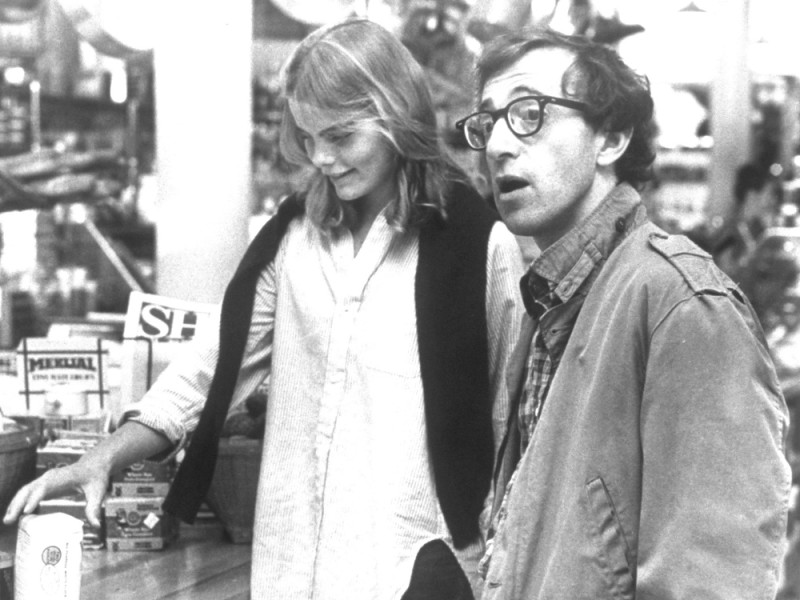

“Manhattan” also happens to portray Allen’s character having a sexual relationship with a seventeen year old girl

Take for instance “Manhattan”, arguably Allen’s masterpiece and a stunning testament to New York and love that also happens to portray Allen’s character having a sexual relationship with a seventeen year old girl. Regardless of what you believe concerning the allegations, this provides a quandary for the average filmgoer. As a cultural and artistic icon, Allen is adding to the conversation about the appropriate age gaps for sexual relationships. There is a responsibility to that which is all his own. The writer John Green recently said that “Books belong to their readers”, echoing Barthes ideology. This only reiterates my point: such a belief strips the author of responsibility of what he puts into the world and leaves interpretation entirely up to the audience.

Yet too often we turn a blind eye to not only rumours of extreme misdeeds but also these proven cases

We are all human. We’re depraved, troubled, damaged and united in our search for comfort. Art is of course the perfect provider for that but there are limits to our acceptance of what is “artistic”. We cannot accuse or speculate about things we may never know the full extent of but equally we can’t ignore the what if’s regarding the lives of artists. There are those who were punished and ostracised for their crimes: Roman Polanski, another respected filmmaker who was charged with drugging and sodomising a thirteen year old girl and fled to France to avoid being extradited, being an example of one. ***Where is the boundary between tolerable and loathsome in art, and why is it that the crime proves more contentious than the supposed criminal?**** Yet too often we turn a blind eye to not only rumours of extreme misdeeds but also these proven cases. On numerous occasions I’ve recommended Polanski’s “Carnage” to friends and I swoon every time Gershwin’s score swells over the New York skyline in the opening to “Manhattan”. Statutory rape. Murder. Molestation. Where is the boundary between tolerable and loathsome in art, and why is it that the crime proves more contentious than the supposed criminal? Is it just a sad fact that some crimes are worse than others, or must we always check our morals at the cinema doors?

Just be mature enough to at least keep in mind where that art came from

So what do we do? Do we boycott these artists, label them fiends and miscreants and banish them to the wasteland of “immoral art”? Do we advertise their misdeeds, ensure every fledgling thinker and culturally aware child is knowledgeable about these crimes and misdemeanours of art? Or do we dismiss them as hearsay, say “innocent until proven guilty” in time to the sounds of popcorn being eaten, insisting that we’ll never know what really happens behind the camera lens? I’m not advocating for people to scrutinise every film or painting or novel they come into contact with or deny yourself the chance to experience the wonderful pieces of art they are. You can like art and not the artist, but accepting that that art is problematic is not a solution. Enjoy the art that makes you happy, gives you peace and teaches you something about our world. Just be mature enough to at least keep in mind where that art came from.

“You gotta have a little faith in people”

So I ask you, what is your favourite Woody Allen movie? Mine was “Manhattan”. I never minded the age gap between Allen’s character and Mariel Hemingway’s character even though I was seventeen when I first saw it, just like her. In the light of Dylan Farrow’s account, however, this film doesn’t sit right with me anymore. Watching it again last week, I found myself wondering how Dylan would have felt as a 17-year-old hearing Hemingway’s final affirmation of “You gotta have a little faith in people” less as a credo to love by and more as a sneer.