Ciar McCormick | Staff Writer

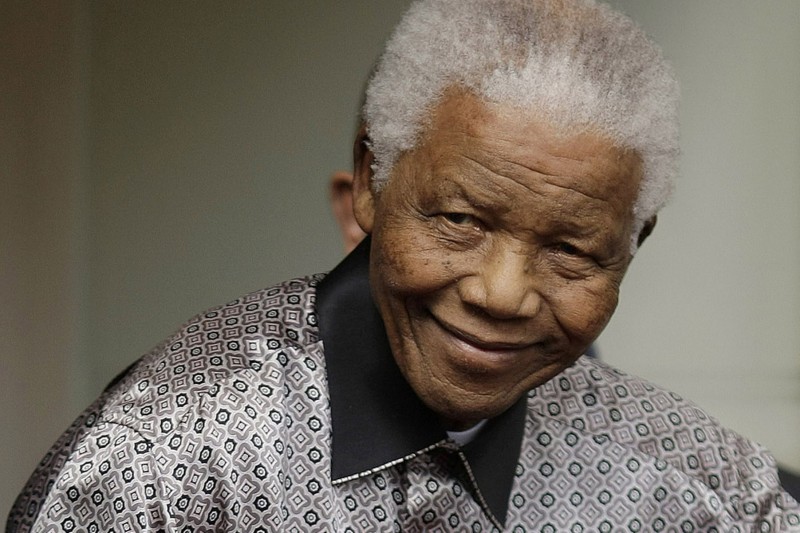

In the wake of the 10 days mourning I find it easy to believe that funerals are in fact not for the dead but for the living. Yes, we are honouring the memory of the recently deceased but this is in fact an outlet for the living, rather than the dead. This same attitude was present during the ten days mourning for Nelson Mandela. Yes, High profile world leaders publicly mourned his passing and praised his legacy; but has his universal hero status consumed Mandela and moulded him into a caricature of a deity forever to be confined to the proverbial pedestal, rather than the faithful legacy of the man himself?

We need to remind ourselves of what he wanted to achieve, and whether he actually achieved it or not.

To properly realise Mandela’s memory we need to remind ourselves of what he stood for. We need to remind ourselves of what he wanted to achieve, and whether he actually achieved it or not. Simply worshiping Mandela will not evoke his memory in any kind of genuine way. Casting Morgan Freeman, a character who has previously played the character of God, as the character of Nelson Mandela will not help achieve the egalitarian standard that he set for himself and for humanity.

Nelson Mandela wanted to end apartheid in South Africa. Although it is recognised that apartheid ended in 1994 – largely with the help and influence of Mr Mandela – it is still the undeniable fact that the miserable life of the poor majority largely remains the same as under apartheid. The main change is that the old white ruling class has been joined by the new black elite.

Mandela preached a legacy of tolerance and forgiveness. He set an example of how apartheid was to be tackled in South Africa and worldwide. Dean Burnett of The Guardian keenly evaluated that praising this legacy of tolerance and forgiveness as an example to everyone, before slandering David Cameron for previously saying Mandela was a terrorist, or exclaiming that the US only took Mandela off the US Terrorism Watchlist in 2008, even if valid, demonstrates neither tolerance nor forgiveness.

The old African National Congress, of which Mandela was a part, promised not only the end of apartheid, but also more social justice, even a kind of socialism during his time in power. The rise of political and civil rights is counterbalanced by the growing insecurity, violence and crime. This has been well documented With the OSAC reporting that “Crime continues to be a key strategic concern for the South African government…In general, crimes continue to range throughout the full spectrum, from petty muggings to ATM scams to armed residential home invasions. These crimes occur with great frequency and throughout every neighbourhood” (www.osac.gov/).

A leader or party is elected with universal enthusiasm, promising a “new world” – but, then, sooner or later, they stumble upon the key dilemma: does one dare to touch the capitalist mechanisms, or does one decide to “play the game”?

In terms of the socialist position of Mandela’s ANC in his time in power, Slavoj Zizek observes that “South Africa in this respect is just one version of the recurrent story of the contemporary left. A leader or party is elected with universal enthusiasm, promising a “new world” – but, then, sooner or later, they stumble upon the key dilemma: does one dare to touch the capitalist mechanisms, or does one decide to “play the game”?… in essence…Nelson Mandela was celebrated as a model of how to liberate a country from the colonial yoke without succumbing to the temptation of dictatorial power and anti-capitalist posturing. In short, Mandela was not Robert Mugabe, and South Africa remained a multiparty democracy with a free press and a vibrant economy well-integrated into the global market and immune to hasty socialist experiments.”

So we celebrate Mandela for transforming an apartheid judged by race to a racialy-deverse apartheid with the masses still living on the margins of the wealth present in the country, for creating a more dangerous and crime-ridden Africa without a strong leftist party, and for not becoming Mugabe.

But if we want to remain faithful to Mandela’s legacy, we should forget about the celebratory crocodile tears. We should focus on the unfulfilled promises of his leadership and learn from them. To fully take this man seriously should we not criticize what he did so as to improve upon his legacy. In light of his moral and political greatness we can assume he came to the end of his life a bitter man. His political triumph and elevation into a universal hero was in fact the mask of a bitter defeat. It could be noted, as it was by Slavoj Zizek that his universal glory may also be a sign that he didn’t really disturb the global order of power.

Could it thus be concluded for a political figure their greatest fear would be; to be accepted, not to be ignored?