The role of Irish soldiers fighting in global battles in the twentieth century has been largely overlooked by history, something which Trinity has recently been playing an active role in changing. With steps taken to begin to honour Trinity’s World War One dead earlier in the academic year, Trinity’s library is now marking the centenary of the Battle of the Somme with a new website commemorating the voices of Irish soldiers who served. Entitled “Fit as Fiddles and Hard as Nails”, this major resource features 1,600 pages of digitised letters, memoirs and diary entries by seven Irish officers, including three Trinity graduates, are included in the project.

Trinity’s library often actively involves itself with national commemoration efforts, as its Principal Curator, Jane Maxwell, points out. Speaking to The University Times, Maxwell emphasises the library’s commitment to making heritage materials easily available to the public. She especially finds the new website an effective tool in achieving this. Keeping reader accessibility in mind, the site features photographs of the original manuscripts, with a transcript alongside them. The idea, Maxwell explains, is to replicate the experience of coming into the library as a reader.

The only exception to this format are the writings of Lieutenant Arthur Callaghan, a Trinity graduate, as just the transcripts of his war diaries are included. This is atypical, but the transcripts were “so good [the website] had to include them”, Maxwell says. The material was transcribed by Callaghan’s great-niece, also a Trinity graduate.

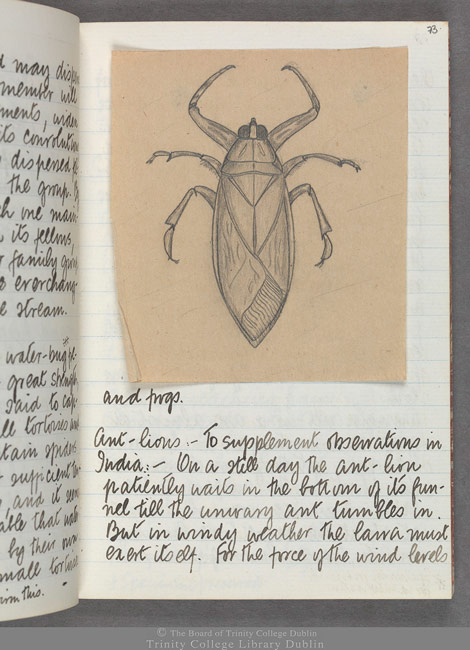

Examining intimate sources such as private diaries and personal letters meant that the project became “much more than simply a transcription process” for Maxwell and her team. She cites the diary of Lieutenant Colonel Charles Howard-Bury as an example, which includes harrowing descriptions of truly horrendous suffering. Lieutenant Charles Wyndham Wynne was another moving example: much younger than his siblings and very much the pet of his family, his untimely death aged twenty left his loved ones devastated.

The invention of new, efficient weapons also meant that the rate of people which were killed was astonishing. Maxwell dubs it one of the first “modern” wars.

For Maxwell, his tragic story sharply highlights the intimate, traumatic consequences of a very global war. Noted as one of the bloodiest battles in human history, the Battle of the Somme took place between July 1st and November 18th, 1916 as the British and French armies fought against that of the German empire. More than one million men were injured or killed, with 3,500 Irishmen believed to have lost their lives in the conflict. It’s very likely that many young men were prompted to fight by a deluded sense of adventure, their courage bolstered by the belief that the war was going to be over very soon and that they would be “home by Christmas”. The invention of new, efficient weapons also meant that the rate of people which were killed was astonishing. Maxwell dubs it one of the first “modern” wars, the horror of which is explored in the library’s diaries.

The accounts could be difficult to read for other reasons too. Soldiers served on both western and eastern fronts and accounts from Turkey or modern day Iraq often feature racist and antiquated language. Maxwell speaks of the difficulty of balancing her respect and admiration for the soldiers and her modern distaste of the terms used.

One of the more surprising insights the diaries give us is that war could also be, quite simply, boring. Lieutenant Henry Crookshank, based in the Eastern Front, wasn’t very hugely in the combat itself and while Howard-Bury suffered at the Battle of the Somme, his time as a prisoner of war was much more subdued. Here, he mainly had to deal with figuring out where to get his next meal, as well as the mundane problem of boredom.

A particularly interesting inclusion is that of civilian Emily Wynne, sister to Charles, whose writings offer insight into daily life in her native Wicklow: “They report that 60 more policemen & a detachment of soldiers have been drafted into Arklow. The women & children have been sent out of the coastguard station & the soldiers installed. No one may be out after a certain hour 7pm.”

Her observations on xenophobia and public unease have an enduring relevance in these post-Brexit times. Maxwell, highlighting how accurately Emily captured the sense of paranoia as people began to “start looking over their shoulder”, attests to this, saying: “Nothing changes — it’s exactly what’s happening now in England.”

Maxwell points out that Emily’s work serves a double purpose in demonstrating the suffering which the war inflicted not just upon the soldiers themselves, but upon the loved ones who stayed behind: siblings, mothers, girlfriends, fiancées, and wives. The importance of the female perspective is made clear in the re-enactment video created for the project, which also includes a woman.

It would have been very much part of Trinity’s culture at the time to support the war effort, particularly given the amount of graduates who were involved in the conflict. Three of the soldiers included in the project were Trinity graduates, and of a social class that informs how history remembers them. Indeed, the men featured in this project are of the Officer class, and middle-class records are more likely to survive as they were considered to be more deserving of preservation. For these men, going to war would have been in keeping with the culture of their family and very much part of their duty to serve King and Country.

Three of the soldiers included in the project were Trinity graduates, and of a social class that informs how history remembers them.

Conversely, foot soldiers would have answered the call for different reasons. Many young Irish men believed it was a necessary step in order to be granted Home Rule. Maxwell notes, however, that fighting for King and Country and supporting Home Rule were not always diametrically opposed. She makes the nuances of the project clear, cautioning against the temptation to find one explanation for so many men enlisting: “There’s no point trying to simplify some of the very many complicated reasons going through people’s minds when they decided to sign up for the war.”

Maxwell has criticised the “eerie silence” associated with the involvement of Irish people in the Great War. Traditionally, their stories were dismissed, or even seen as something shameful, which has hindered preservation; “If things aren’t respected, they won’t survive … and so much has been lost already.” She speaks of the shock and pain that the soldiers must have experienced after surviving a traumatic war only to return to a country which did not want to hear their story.

The library’s project is proof that this dismissive attitude is certainly changing. Its very existence makes it clear that the stories of the Irish soldiers who served in the Great War are significant and worthy of preservation. As Maxwell puts it, this is a “very big fuss” being made by the most important library in the country. A huge amount of effort was dedicated to telling stories which are typically brushed over in Irish history. She believes that this new expression of interest in these stories is indicative of a more sophisticated and complex society, aware of the nuances of history, and credits better education and access to the internet as factors which have led people to “reject simple stories”.

The “roaring success” of the World War One Roadshow in Trinity two summers ago is certainly evidence of this. “It’s not either/or,” Maxwell affirms, emphasising that it is possible to recognise the courage and sacrifice made by those who served in the Great War as well as those who fought in 1916. For Maxwell, uncovering these oft-hidden stories is an “incredibly important” part of our national heritage. She expresses the hope that the initiative may inspire other individuals who have primary resources of their own to appreciate their value and potentially to share them with the country.