In October of last year, the Irish Times reported that Ireland had been invaded by “an army of fake Twitter accounts”. RTÉ broadcaster Philip Boucher-Hayes, one high-profile account targeted by the apparent bots, saw his followers increase from a growth rate of roughly 150 people per week to as many as 2,000. All of the apparent Twitter bots had several things in common: they had Irish sounding names (O’Leary and O’Connor were particularly popular), no profile picture and Twitter handles ending with eight random numbers as if generated by a computer. As Una Mullally put it in the Irish Times: “It could be something, it could be nothing.”

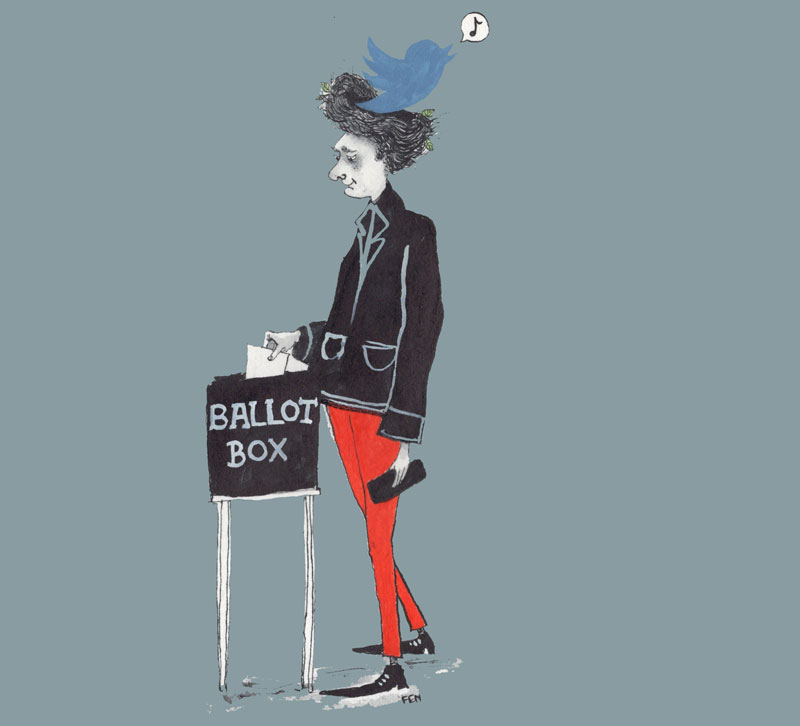

Still today, hundreds of bots continue to pop up and follow the same popular Irish Twitter accounts, and while many have remained idle, some have developed a clear occupation: to amplify and dilute dialogue on the eighth amendment referendum. One example is an apparent fake account under the name Karen O’Connor following Boucher-Hayes and tweeting on the handle @Karenoc83270164. Since joining the platform at the end of January, the account has racked up 816 tweets. The majority of the posts are retweets from pro-life figures and groups. When the account tweets organically, the English is disjointed and in each case, words are followed by a full stop rather than a space.

While this is only one account, trawl through Twitter for long enough and you will come across similar accounts retweeting, liking and replying to tweets on the eighth amendment. Notably, the profiles often appear to be that of women, and their following list includes Leo Varadkar, The Late Late Show and Fáilte Ireland amongst other generic Irish accounts.

Maybe some accounts genuinely are clueless Twitter users who can’t get their heads around the basics of using a keyboard. And currently, the presence of these suspicious accounts actually tweeting about the eighth amendment does not seem too widespread. But considering the effects bot and troll tactics have had on elections in America, Britain, France and Mexico over the last few years, it is a worrying development. The furtive use of bots and fake accounts appears to be an increasingly normal feature of modern-day politics.

People would be naive to think that “little old Ireland” is immune to foreign interference in elections.

Social media was important during the 2015 marriage equality referendum, but even in the three years that have passed since, the platform’s place in politics has grown ever more important. Equally, its problems and the ways to manipulate it have become more sophisticated. The eighth amendment referendum will be Ireland’s first vote for which social media will play host to such a large proportion of the political debate, and for many voters, it will be the debate chamber where their mind is made up.

Fearing the misuse of social media and political advertising in Irish democracy, Fianna Fáil TD James Lawless has tabled a bill to make online advertising in Ireland more transparent. Speaking to The University Times about his bill, Lawless says that people would be “naive” to think that “little old Ireland” is immune to foreign interference in elections.

Lawless admits that he is worried about the use of foreign money in the upcoming referendum and fears Fine Gael’s current opposition of the bill is leaving Ireland vulnerable. “It doesn’t have to be Russians, it could be loads of people. We just need to know if people are running political ad campaigns online, and if they are putting serious cash behind them we need to know who is funding and who is sponsoring it.”

Worries exist on both sides of the eighth amendment campaign about the influence of social media. Speaking to The University Times, Annie Hoey from the Coalition to Repeal the Eighth Amendment expressed her anxieties: “We need to only look at the last two years and the impact social media can have on things. It’s very easy for people to take things at face value. I think if you have a lot of money its extremely easy to manipulate social media.”

In contrast, Cora Sherlock from the Pro-Life Campaign, in an email statement to The University Times, said that their worry was rather the “mainstream media” that could “not be trusted to report on this referendum in a fair and impartial manner”, hence why social media was so important to spread their information.

Facebook is very very sophisticated at microtargeting. They sell the ability to approach people who they know have certain political views

In 2012, Ann Ravel, a former Commissioner of the Federal Election Commission under President Obama, attempted to introduce legislation similar to Lawless’s in the US. Her attempts to prevent potential foreign interference and foreign advertising around US elections saw her receive death threats and a barrage of online abuse, something she now believes was propagated by Russian bots and trolls hoping to meddle in US elections.

While social media has opened politics up to greater participation and organisation, social media is, for Ravel, still more of a threat than an aid to democracy. Ravel highlights in particular the ability of platforms to sell “microtargeting” as a valuable commodity for those who wish to target specific groups with misinformation. Speaking to The University Times, Ravel explains: “Facebook is very very sophisticated at microtargeting. They sell the ability to approach people who they know have certain political views because of the kinds of things they click on, the kind of things they have in their feeds, what their friends are into, what organisations they go onto, what they buy.”

“It’s astounding how sophisticated they are. It’s purposely done to sway people based on what they know about their emotional make-up and they know so much about people’s emotional make-up based on who they are friends with”, she says.

Social media, which was initially pitched as bringing people together, is now the most important tool for sowing division and disseminating political propaganda

As political debate continues to migrate online, other issues such as polarisation and increasingly negative news also appear to be exacerbated by social media. Speaking to The University Times, Michael Bossetta, a PhD fellow at the Centre for European Politics in the University of Copenhagen and the host of a podcast on social media and politics, explains that studies have shown that negative news performs better on social media, with citizens opting to share articles in outrage more often than in celebration. According to Bossetta, this has lowered the level of debate in some mainstream publications to “mud-slinging” simply because it performs well online.

But the result is a more negative debate and increasing polarisation between the citizens who fall on different sides of the same issue. “It may be negative for democracy from an information standpoint but positive from a participation standpoint”, Bossetta relays. “People are getting involved who have never got involved before but maybe they are doing that on bad information.”

While Bossetta does not necessarily buy into the idea that we are all existing online in ideological echo-chambers, he warns that coming up to any election or referendum, we must be aware of the power of algorithms. “Especially on Facebook if you like content that you agree with you are likely to get more of that content. You’re going to end up seeing more of one side than the other and this will make you feel like a movement is bigger than it is.”

“All of these platforms log every time you make an interaction. So you may think that your side of the referendum is running away with it and then you may not feel like you really have to vote.”

Hoey, from the Coalition to Repeal the 8th, argues that ultimately, social media is not as important as face-to-face canvassing with voters. Ravel, however, argues that social media, which was initially pitched as bringing people together, is now the most important tool for sowing division and disseminating political propaganda.

When it comes to advice for Irish voters, Ravel says: “Hopefully Ireland will not be influenced by outsiders as Brexit was, as France was, as Ukraine has been. And hopefully that wont happen in Ireland. But what people do need to understand is they need to be thoughtful about who is sending these messages and why. If they don’t know the source of it, they should demand to know the source.”