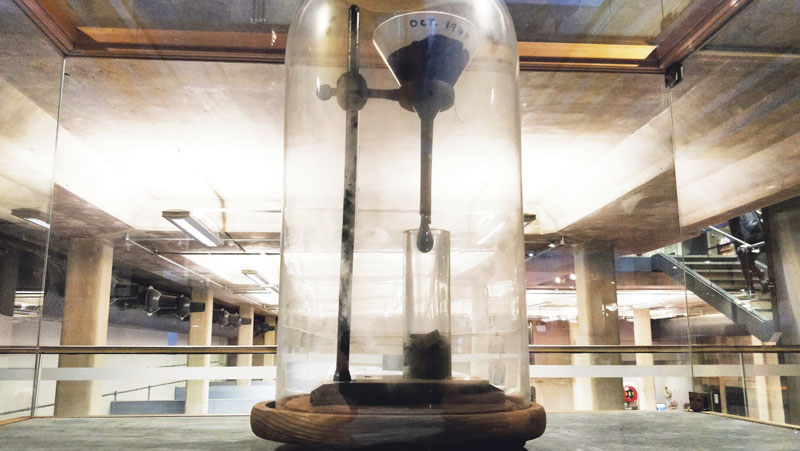

Hundreds of Trinity students walk in and out of the Berkeley Library every single day, without ever realising they are in the midst of a science experiment that has been ongoing for over 70 years.

The Berkeley Library represents one of only three locations worldwide to contain a pitch-drop experiment. What makes the Trinity experiment unique however, is that it was the first instance the drop was captured on camera. The University of Queensland’s more famous experiment missed filming its drop in 2000 because its camera was offline at the time.

The experiment aims to demonstrate the high viscosity of pitch, a material that appears to be solid at room temperature but is in fact flowing, albeit extremely slowly. Drops occur approximately every decade. Speaking to The University Times, Stefan Hutzler, Associate Professor of Physics in Trinity, and one of the driving forces behind the recording of the experiment, described it as “an illustration of viscosity. If you have a drop of water, it falls off a spoon very quickly because the liquid isn’t very viscous; if you have honey and you let it drop off your spoon, it forms a long thread till it eventually detaches, it takes a long time. And in the case of pitch, it takes 10 years or so to detach”.

The Berkeley Library represents one of only three locations worldwide to contain a pitch-drop experiment

The origins of the pitch drop experiment in Trinity have been lost to history, but it is presumed to have been initiated in 1944 by a colleague of Ernest Walton, the esteemed Nobel Prize winner and Trinity professor. But despite its grand beginnings, the experiment fell by the wayside and sat unattended on a shelf for many years, continuing to shed drops uninterrupted while gathering layers of dust.The modern chapter of this story began in the 1980s, when dusty cupboards were emptied of their antique contents in the School of Physics at Trinity and the experiment was moved to a new location. Yet it’s important to note that despite being titled “the pitch drop experiment”, it lacks most of the qualifiers needed to classify it as such.

Hutzler acknowledges that the tumultuous past of the experiment and its somewhat lack of scientific rigour is problematic. “It’s not really an experiment, a proper experiment is controlled. Nothing in there is controlled. We don’t even know what it is.” Shane Bergin, Assistant Professor of Science Education in University College Dublin, was another driving force behind the recording of the pitch drop while he was a staff member in Trinity. He also vouched for the removal of the “experiment” title but asserted that this may have added to the interest surrounding it. “It’s not an experiment. It was designed as a curiosity, and I guess it’s interesting because it is a curiosity, because for someone who isn’t a scientist, they can be as enthralled by it as someone who is a scientist or a mathematician.”

Having been moved to a new location in 2013 outside the confines of a cupboard, physicists at Trinity noticed that another drop was beginning to form. Starting in April of that year they began to monitor it, setting up a webcam that could be watched online by anyone.

At around 5pm in the evening of July 11th 2013, physicists in Trinity captured footage of one of the most eagerly anticipated and exhilarating drips in science.

The time-lapse video received global media attention, with the experiment being featured on RTÉ News, the Huffington Post, the Wall Street Journal, New Scientist and the National Geographic. When asked about what it was like, as a physicist, for a science experiment to garner that amount of popularity and media attention, Hutzler had only one word: “Embarrassing.”

“I mean, we didn’t really do much, the stuff was there. Shane and I just decided to put a camera on it, a very poor resolution camera and all of a sudden you get RTE interviewing you. You do good scientific work and you get no publicity, and then this thing comes along and all of a sudden you make it on the main evening news. I thought that was bizarre.”

Despite this, it is clear that Hutzler still holds this experiment, or perhaps “non-experiment” in dear regard. He points out that the clock on his bookshelf behind me is the very clock present in the video that recorded that momentous pitch drop. He also tells me about a past tutee of his, Ria Murphy, now one of Ireland’s leading aerial silk artists. In 2016 Murphy premiered “Black Pitch Pitch Black” to a sold-out venue at Dublin Fringe, an aerial show inspired by the pitch drop experiment. It explores the psyche of a women accompanied only by the pitch drop experiment as she delves deeper into seclusion as she waits for the drop to fall.

For Bergin, despite its imperfections and flaws, the pitch-drop is still an important part of his scientific life, particularly in the area of science outreach. He is currently trying to set up pitch-drops in various secondary schools around Ireland in order to ignite students’ interest in science.

It’s not really an experiment, a proper experiment is controlled. Nothing in there is controlled. We don’t even know what it is

As a result of capturing the drop, the Trinity team estimated the viscosity of the pitch by monitoring the evolution of this one drop. But there was no significant scientific payoff from this experiment; in the article written by Bergin, Hutzler and Denis Wealre in the May 2014 issue of Physics World, they note: “We learned nothing we did not know before.”

So, why the popularity? The pitch drop experiment, it seems, has all the ingredients for the perfect story, the mystery of the origins of an experiment established by a forgotten scientist, confined in an obscure dusty cupboard for decades. The build up, a decade-long wait between each drop, makes each one all the more noteworthy. And, of course, the tragedy of time is always there too. Prof John Mainstone became the curator of the experiment in the University of Queensland in 1961, and looked after the experiment for 52 years without ever seeing a drop fall. Hutzler adds “people were aware of this experiment in Australia, of the mishaps that happened there that it was never recorded. But people knew something was there, a drop was there, they’d forgotten about it but it was sort of woken up again. So that’s why we got this attention. We came out of nowhere, nobody knew we had this and suddenly, it dropped first.”

Bergin cites the public interest in the pitch drop as proof of an appetite in the general public for more media attention on scientific endeavours, “I thought it was amazing that people were so interested in curiosity. I think it showed that there is a general public appetite for scientific curiosity, a curiosity that the media − particularly the Irish media − often miss”.

With another drop not expected for at least another four years, current students may not want to hold their breaths in hope of witnessing the spectacle any time soon. But maybe next time you pass through the Berkeley, take a minute to look at this 74-year-old experiment that shows us the value of slow science, the importance of patience, and, above all, the ability of a good story to capture the attention of the masses.

As Hutzler so eloquently put it, “I find it very fitting that the experiment is kept in the library. The library has something timeless about it and I think this is just something of the same. If you look at it from day to day, nothing happens. So it’s a bit like the books that have been written hundreds of years ago, yet you can still see them and read them. Time passes slowly I think in a library and maybe that’s similar to this experiment.”