An eternal problem on Trinity’s campus? Space. Like today, in the 1940s and 1950s Trinity’s book collection and student numbers were swelling. The College searched for solutions, and in 1959 a Babelesque proposal was made to build a kind of building-bridge across Nassau St to connect Trinity with the National Library.

The go-ahead was refused by Archbishop McQuaid primarily on sectarian grounds: until 1970 Catholics were banned – on his orders – from attending the College. Instead, a competition was launched, calling for designs for a library of Trinity’s own. It was made possible by a dynamic funding campaign that included the scintillatingly titled film Building for Books – which even made it to general release.

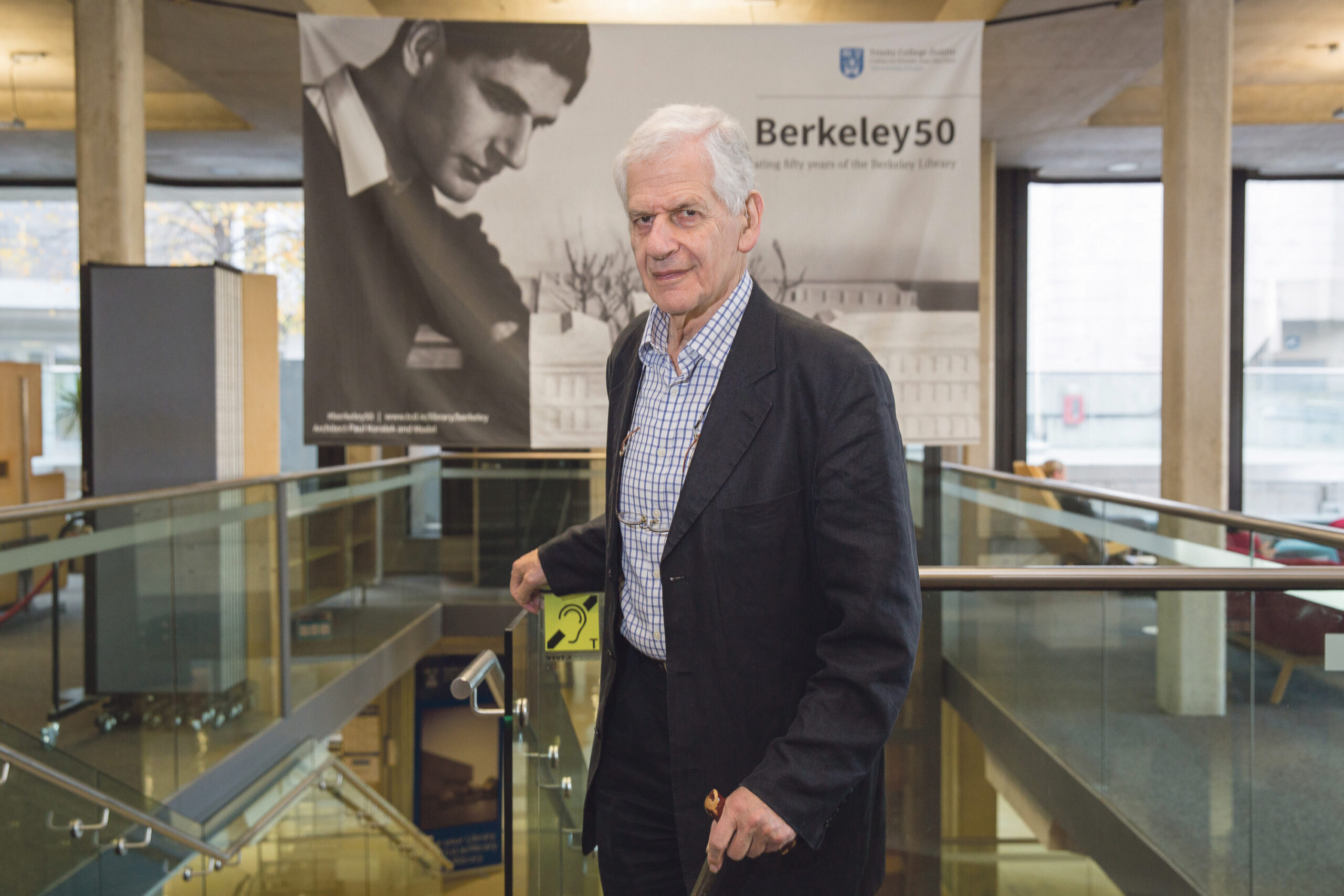

Living in a bedsit in New York and working at the practice of Marcel Breuer – the Bauhaus architect and furniture designer who made svelte functionalist pieces that now epitomise luxury Modernism – was Paul Koralek. Despite the fact that he’d never visited Trinity, Koralek’s entry to the competition impressed a panel of esteemed judges, including a former librarian of Harvard, the Earl of Rosse, and a curator to the famed 1951 Festival of Britain. He beat 217 other entries.

At the time, there was understandable anxiety in making an addition to Trinity – no building had been added to any of the campus squares since, in 1857, the chisels that carved the garlanded Museum Building had been put to rest. The report of the jury award makes clear that Koralek had cracked this respectful code. “The architectural relationship to the older buildings is good”, it reads.

Paul George Koralek was born in Vienna in 1933. Following the Anschluss, he left for London with his family at the age of five. Having left school, he studied French language and culture in Paris at the Sorbonne but left after a year for a place at the Architectural Association in London, graduating in 1956. There he met Peter Ahrends, who had come from South Africa after his family had fled Berlin, and Londoner Richard Burton, whose family were prominent promoters of Modernist film and theatre.

At the time, there was understandable anxiety in making an addition to Trinity – no building had been added to any of the campus squares since 1857

On winning the library’s commission, Koralek established a practice, called ABK, with two of his classmates. As Greg Sheaf, a Berkeley librarian of Physics and Chemistry books explains to me: “It’s a lovely story, because Koralek and his two mates – after they came out of college they went round Europe looking at nice architecture, looking at Le Corbusier and nice cathedrals … they said: ‘When we hit the big time, we’ll form a firm.’ And then Koralek did.”

Likewise, Ellen Rowley, the architectural historian and author of More Than Concrete Blocks: Dublin City’s Twentieth-Century Buildings and Their Stories, says that “Koralek always understood himself in relation to his two partners, especially in terms of their practice here. As such, Koralek would refute that he had an identity or meaning in Ireland without the other two”. Design as total, then.

The Berkeley Library, as it became known, is a rectangular concrete structure rising from a podium. To the west, the facade carries occasionally glittering granite blocks above a base of concrete strata. Where broken, it is by bronze-framed, double-height windows curved like motorbike visors. But the facade masquerades in further virtuosity: rudely moulded water downpipes jut out, preserving something medieval in its face of Modernity.

The library’s entrance, to the north, is gained by steps to a plaza, providing a kind of outdoor ante-room, for dignified chatter between the Berkeley and its proud neighbours: the Old Library, and Museum Building. The north facade itself is forbidding, concrete and closed, until one realises that its gravest element, its overhang, provides shelter to students shuffling past, or puffing at damp fags.

Inside, a staircase is backlit on its landings by frosted glass to the outside, which palely lights the treader’s way. The stairs lead to a reading room on the first floor, patterned by several strict rows of deep blue leatherette desks. These are numbered, as if members of a fleet. The room’s volume is treble-height and therefore holy. But there is play about: readers, on the level above, from a mezzanine, spy down.

Koralek’s Library brought Brutalism to Ireland. The movement is seen as a late strand of Modernism, emerging from a post-war context. Earlier architectural modernisms had, in a changed and changing world order, come to embody something of a nasty authoritarianism.

But yet, after the cleaving stress of war, society was still in need of assurance. Brutalism then, would respond to this paradox: it would be at once monumental and civic. The best known of Brutalism’s still-standing exemplars include the rock-like formation of Denys Lasdun’s University of East Anglia, the very brown Barbican Centre in London, and the single-piece city of the National Theatre, nearby.

Though the intention behind Brutalism was originally to extend and improve architecture’s relationship to the public, the aim was often lost in translation.

Valerie Mulvin, director of McCullough Mulvin, a firm that has assumed through square competition the role of Trinity’s main architect post-ABK – having built the Ussher Library, Long Room Hub, and most recently Printing House Square – explains the gap as a result of the structures surrounding architecture.

“I believe that the failures often associated with Brutalism are more often the fault of poor social policies, which – although well intended, such as the provision of massive amounts of social housing in the 1960s in Britain – left many communities disenfranchised and unsupported, with buildings not maintained and a poorer and poorer spectrum of tenants with difficulties. In Switzerland, the same kind of buildings would be sought-after apartments.”

Both Sheaf and Rowley acknowledge a similar theme of the gripe against Brutalism. To both, the misgiving begins with language. Sheaf unpacks Brutalism’s French roots: it comes from béton brut, meaning raw concrete – which delighted Le Corbusier’s on account of its potential for what architects term “structural honesty”. Concrete can be the load-bearing core of a building as well as a finishing surface.

The materials of the walls, the divisions, the floors are mind-bogglingly tactile – as in, I go past with my hands and touch with my eyes

But this “truth” to a building can be stark, and the brutal of Brutalism was underscored by detractors. “Brutalism sounds like an unkind label somehow, associated as it was with overscaled and machine-made buildings which ultimately seemed divorced from human experience”, Rowley says. However, she elaborates on how through ‘good’ Brutalism as in the Berkeley, the opposite happens and concrete becomes more amenable. “The materials of the walls, the divisions, the floors are mind-bogglingly tactile – as in, I go past with my hands and touch with my eyes, with my mouth.”

The building’s uptake by the senses is fostered by what Rowley describes as “hand-made Modernism”, and at the Berkeley, came about in part by limitations outside ABK’s control. The pre-cast concrete structure Koralek had planned in his original design, had to be revised because Ireland at the time did not have the resources to make it. Instead, the concrete was mixed on site, and poured into wooden cases built by the contractor, G. & T. Crampton. This allowed grains in the Douglas Fir wood to be set into the drying concrete, visible at various points.

On a tour, given by Sheaf, I learn however, how specific the mark-making is. Koralek only let the wood texture completely flat planes, while curves, such as the buildings skeletal and load-bearing columns, are smooth. This kind of detailing has had its accusers, Rowley explains – the judgement of “overwrought” being snidely levelled. Indeed, there is an ill-ambiguity to Harry Allberry’s comment in the Irish Builder in 1967 – “so marked is the timber pattern that one expected to see the sap oozing from it”.

But detail wasn’t just set in the concrete: the building’s fittings were also remarkable. The current desks are original, made by the Ardee Chair Company in Co Louth. Sheaf tells me of a visit to the library about a decade ago, by the men who had made the desks. “The lads were in their 80s” and gleeful in the endurance of what they had made, half a century earlier. Admittedly – and I wonder if by necessity or by a drive for comfort – the men’s original wooden chairs have been replaced by what serve now, but for the interested, just one original occasional chair, is still around: look out for the wire one by the visiting readers’ desks.

When I ask Sheaf about the public perception of the Berkeley – he is an experienced tour-giver – he explains that it depends on “how it is framed”. By this he means, that if you point out how beautiful the Old Library is, and then suggest the Berkeley as some kind of comparative monster, people tend to dislike it. But if you point out the amazing details, and emphasise the building’s embodiment of the 1960’s machine-age optimism, then people see it “differently”. Architects – as their own enclave of the populace – he says, are another breed. Their passions don’t need encouragement: established architecture firms often get in touch with the library, to say that they are sending junior members to visit, on, what Sheaf calls “their pilgrims”.

Sheaf emphasises how both the Arts Block (also an ABK Brutalist piece, finished in 1979) and the Berkeley each belong to their own time. While in the case of the Arts Block, that implies “almost a feeling of brown to it” and “leather patches on the elbows, bearded lecturer kind of feel”, the Berkeley “has a feeling of the white heat of technology: that idea that we were about to go to the moon”. Yet, Sheaf tempers carefully, “horrendous things were still going on” but, still, he insists that the 1960s contained a feeling of endeavour and striving. “The whole civil rights movement was about making things better. And I think that in some ways is part of the architecture of the Berkeley.”

In thinking of the Berkeley as “belonging” to the 1960s, it is easy to become blind to the subtle but persistent changes it has in fact endured. It is only when one steps back, that one can consider how different the library must have been before the Ussher and Lecky libraries existed, and the airport like marmoleum interchange zone between all three was built. Before, the floating stairs that penetrate the Berkeley from this approach, never existed. Back then, the computer space downstairs was Ireland’s first university art-gallery. The space, which is high and bare, and must have worked as an ideal ‘white cube’, was inaugurated with a solo Henry Moore exhibition in 1967. Two years later, a Picasso exhibition was hung (the catalogue of which shows not just paintings but his prints and ceramics too).

Obviously, the PCs and pen-style meeting rooms which now occupy the basement are hard not to bemoan in the context of learning this history! But despite these changes and replacements, which, perhaps have not been for the better or for the sake of strict necessity, Sheaf is at pains to point out how the Berkeley, by virtue of its strong sense of self, has retained and will always retain an essential soul.

Bringing detail to bear, Timothy Casserly, a recent Trinity art history graduate, points out these changes specifically – the replacement of a Henry Moore sculpture with the bronze globe and its improbable flame on the forecourt, a veranda now rendered inaccessible, the barren piazza that fills in the space between the Berkeley and the Ussher – as forcing the Berkeley into “maladjustment”. But in the context of the fates that befell most of Dublin’s Brutalist history, like the knocking of both the Hawkins and Pollard Houses, the Berkeley, even if altered is “an unusual, but deserved feat in modern-day Dublin”, he says.

In appraising Koralek’s life’s work, as this article is guilty of, discussions and passions seem to inevitably return to the Berkeley, his first work. To Sheaf, I wonder nervously, if this suggests that greatness came too soon, never again to be eclipsed. But Sheaf doesn’t think so, and in any case, we are lucky if we reach greatness just once. Making monuments after all, seems brutal.

Paul Koralek died on February 7th, 2020, and is survived by his two daughters Katy and Lucy.