Molly O’Cathain is an audacious young theatre designer who calls into question the meaning of art in fragile and fractured times. The Trinity graduate and co-founder of MALAPROP Theatre found herself stuck in her parents’ Dublin home after returning from London in what was meant to be a brief hiatus at the onset of the pandemic.

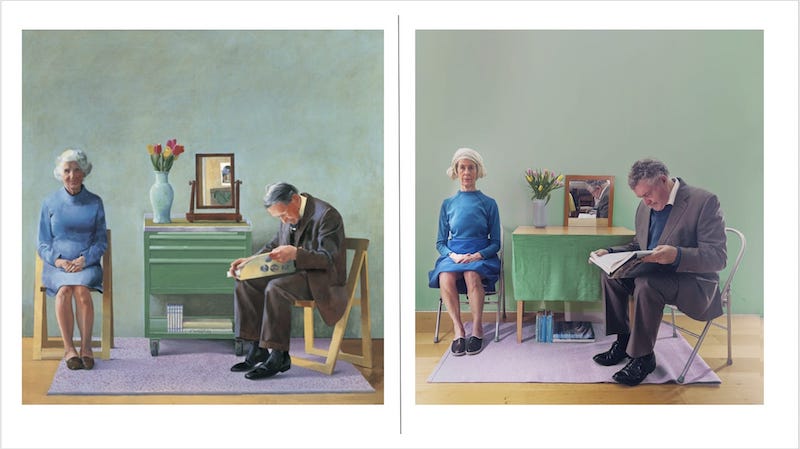

A halt on theatre production left O’Cathain longing for a creative outlet – leading to the re-creation of over 50 iconic portraits from her family home. “Parental Pandemic Portraits” took the internet by force. O’Cathain sat down with The University Times to reflect on the meaning of artistic resourcefulness in a time of crisis.

During the first lockdown, O’Cathain and her parents, Brian and Liz, selected a renowned artwork after dinner to recreate. Night after night, she shot various double portraits of her parents. The family weren’t picky about what they wanted to emulate, drawing from a breadth of work by Renoir, Vermeer, David Hockney and Klimt. O’Cathain tells me that she began the project because she “was bored and frustrated about everything being shut down”. Pausing, she adds: “There’s something about that alone. It was such an unusual process – it would not have happened at any other time.”

It was such an unusual process – it would not have happened at any other time

Each portrait took a few hours to pull together, between moving furniture and dressing the set. “My parents are very much my collaborators”, says O’Cathain. “We’d pick a painting – which had to have a feeling of achievability – we’d then hunt the house for bits and pieces to put it together with, and then to decide where we’d take it.” This allowed her resourcefulness as a theatre maker to shine through: “Most shots were taken up against roller-blinds because they serve as an off-white background. Other than that, we used bits and bobs from around the house. There was no extensive number of things, there was no dressing up box. It was more scarves with safety pins and tape, old pairs of tights, long johns, pieces of fabric and pots and pans.”

The series went viral, with O’Cathain appearing in publications such as The Guardian, The BBC and The New York Times. Looking back, she remembers the project as “a connection and a way out of the weird little bubble” of lockdown. “It became a reason to talk to people. It brought this feeling of joy – it felt similar to what I was doing when I did my real work.”

Reconciling the now broadened parameters of her own work, thanks to this project, O’Cathain affirms that lockdown means “everybody has the chance to see and utilize what life is like without the pressures of modern life”. Her experience of art has changed as a result.

It became a reason to talk to people. It brought this feeling of joy – it felt similar to what I was doing when I did my real work

O’Cathain isn’t currently interested in digitally-recorded theatre, saying “it’s too young and too naïve in its direction”. She believes that “there needs to be a reason why we’re watching it on a laptop and to ask why this makes sense and why it is okay”. Indeed, in a newly adapting world of digital technology, the philosophical role of art relative to the question of how to re-define it has never been more important and worthy of investigation.

O’Cathain sees that “the whole world is turned upside-down and the art form that we know is no longer available. We have to be supportive of experiments but I think moving forward, if it is going to continue, we will need to have some sort of rigour in how we continue to make the work feel urgent and engaging and which forces you to be present and forms a community”.

An environment must be created in which an artistic imagination can meet with a technological imagination capable of creating a new level of collaboration and expression, she explains. “These are the things that we like about live art and they need to be carried across for it to be worthwhile”, says O’Cathain. “Otherwise, we may as well watch really good TV.”

This period should not be remembered as one of stagnation by an emerging generation of artists. Life in lockdown flows with fewer interruptions, offering artists such as O’Cathain new possibilities. Human life, experience and society may be irrevocably changed by the pandemic, but what endures, unchanged, is the need to turn it all into beauty. O’Cathain’s portrait project shows that art is really about interpreting our own experience, and that we might as well make do with what we have available.

Molly O’Cathain’s “Parental Pandemic Portraits” can still be viewed on her Instagram and Twitter.