It’s that old joke, isn’t it? How can you tell if someone went to Trinity? Don’t worry, they’ll tell you. I’ve had that joke loitering in my mind a lot lately, not only because nothing fills me with a greater satisfaction, gives me that buzz or delights me more than dunking on grand old Trinners, but because it is a rather apt summation of a trend I’ve noticed in Irish literature lately.

2020 was another stunning year for Irish literature, no doubt helped immensely by the release of two great debuts: Naoise Dolan’s Exciting Times and Niamh Campbell’s This Happy. Dolan’s novel, which centres around a sardonic young Irish woman named Ava caught in a love triangle in Hong Kong, was the talk of Lockdown One. The novel is a fresh and humorous take on the messiness of relationships and introduced some of the well-needed queerness that Irish literature has been lacking of late. Campbell’s novel, on the other hand, is a far more literary affair. This Happy concerns another young woman, Alannah, looking back at the relationship she had in her early-20s with a married man. The star of Campbell’s novel is her complex prose which, deservedly, earned positive comparisons to McBride.

Since both of these novels were written by young women (and young Irish women at that) they were, of course, compared to the work of Sally Rooney. (Aside: is there any more liz-lemon-eyeroll.gif-inducing piece of PR than a Rooney namedrop? The name Sally Rooney doesn’t really mean anything anymore – it’s pure PR shorthand now, only used to help sell books, in much the same way that any book that is vaguely topical is now “essential” or anything written by Matt Haig is “good”.)

However, for once, the Rooney comparison is fitting. The connections between Exciting Times and This Happy to Conversations with Friends, Rooney’s debut novel about a ménage à quatre between Frances and her friend/lover Bobbi and a married couple, are pertinent.

Is there any more liz-lemon-eyeroll.gif-inducing piece of PR than a Rooney namedrop? The name Sally Rooney doesn’t really mean anything anymore – it’s pure PR shorthand now

For example, the main characters of each novel, all of whom are young Irish women, at some point proclaim themselves to be socialists. Rooney’s Frances actually goes one further and self-describes as a communist who sees no reason “political or financial” in ever earning more money than what GDP would be if divided equally amongst everyone. Each novel also employs a knowing first-person narration, the protagonists often providing snarky asides and droll assessments of the events before them. And there is, of course, the obvious connection in the plots, each of which concerns a woman becoming invested in a toxic relationship with an older man. The final connection is between Rooney, Dolan and Campbell themselves. They are all Trinity educated, which leaves me asking a question about three of Ireland’s biggest debuts of the last few years: why do Trinity graduates keep writing the same novel?

It seems to me that what we are witnessing is the founding of a “school”. Up until a couple of decades ago it was common for creatives to be informally grouped together as “schools”. Schools usually comprised of artists and writers who lived in the same area, knew each other personally and whose work often shared common traits, for example there was the New York School that included Frank O’Hara, John Ashbury and Kenneth Koch, and the Barbizon School of Jean-Francoise Millet and Jean-Baptiste-Camille Corot. I believe that due to the abundant similarities in their work, their shared education and the comparisons that are often drawn between them, Rooney, Dolan and Campbell can lay claim to being a genuine school – the Trinity School.

It feels suitable as a title, not just because of each writer’s genuine connection to Trinity, but like Trinity campus itself (simultaneously in the very heart of Dublin and in its own world) the writing in these novels can often take place deep within its own microcosm and rarely reflects reality. For example, in her review of Exciting Times for the New York Times, Xuan Juliana Wang denounced Dolan’s “superficial evocation” of Hong Kong as entirely missing the “textures of a real city that is sharply divided along generational, ideological and class lines”.

I believe that due to the abundant similarities in their work, their shared education and the comparisons that are often drawn between them, Rooney, Dolan and Campbell can lay claim to being a genuine school – the Trinity School

I have often described myself as red as the sole of a Louboutin, but even I find fault in Frances from Conversations with Friends’ paltry excuse for comradeship. Her communist views are often just that, views, and never does she actually partake in anything resembling action throughout the novel. Perhaps they misheard the Internationale lyric as “so comrades, come dally”.

Depending on your personal view, the Trinity School is either hugely exciting or everything that is wrong with novels nowadays. Their books never seem to provoke tepid reactions – you either love them or you hate them. But that’s a whole other issue.

Circumnavigating back to my opening joke, I feel I now need to amend it. How about: how can you tell if a writer went to Trinity? Oh, honey, you’ll know.

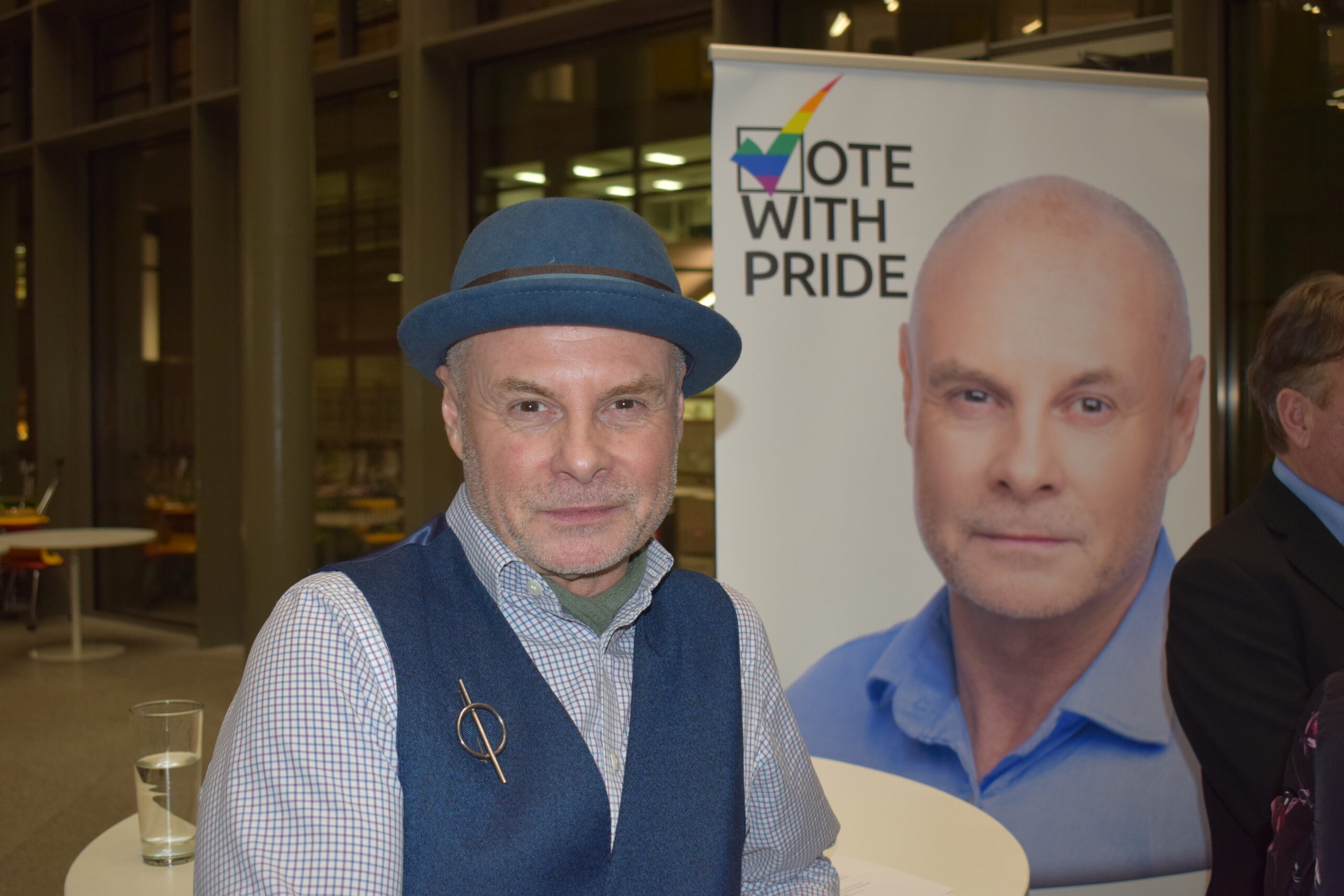

Barry Pierce is a book critic and culture writer.