As part of our series of interviews with this year’s provostial candidates, we will be publishing the transcripts of our discussions with Prof Linda Doyle, Prof Linda Hogan and Prof Jane Ohlmeyer. The text has been lightly edited for the sake of length and clarity. The transcript for our interview with Doyle is around 6,500 words long.

For those who find reading this too herculean a task, we have also condensed the interview into a more digestible overview, as well as a “top five takeaways” piece. This interview was conducted by Jane Cook, the newspaper’s Science & Research Editor and the reporter assigned to Doyle’s race.

Cook: Well, I’ll start easy. What are you most excited about heading into the Provost campaign, for yourself and your team?

Doyle: So the most exciting thing for me is definitely the fact that you get to discuss vision and ideas, and I’m dying to discuss the ideas that are in the Imagine Trinity manifesto. I think one of the most powerful things actually about this election is the fact that everyone has something to say and wants to discuss the future of Trinity. So that, to me, is the most exciting bit. The vision, the ideas, discussing those, coming up with new ones.

Cook: Yeah, definitely. Do you want to maybe start by telling me which is your favorite point in your manifesto, and why?

Doyle: That’s a harder one to answer, without a doubt Jane. So if I have to pick one thing, I would say… so the manifesto is set around seven different themes, and if I was to say one thing – I couldn’t pick any one of those themes – but I would say it’s the overall intent. And the overall intent for me is saying that against the odds, Trinity has loads to be proud of – we’ve achieved loads and imagine how much more we could be by addressing some of the challenges that we have. And it’s that motivation to be even more, that all of those points are about… There are amazing students and amazing staff in the university and as I said against the odds of challenging funding, of the third-level sector receiving kind of poor investment, against the odds of an awful lot being on people’s plates, we do a huge amount and achieve a huge amount. And we can still be much, much more. That’s the overall point, I suppose, that I’m trying to make.

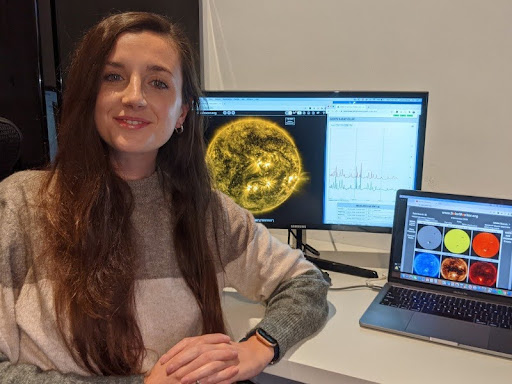

Cook: I noticed something that sets you apart from the other two candidates, in particular, is your background in scientific research and your commitment as Dean of Research, so what role do you think research has to play in your vision for a better Trinity?

Doyle: I suppose there’s a quick answer to that, and I would say it comes into it all over the place. And there’s a longer answer to that. So maybe I’ll just make it in a few different points. So, to me, the core mission of the university is teaching and research. We’re here for, and because of, the students, and we’re here to do great research and to change the world around us. So a lot of what’s in my manifesto is about taking back time, so we can focus on teaching and research.

The way I think about it is that for every single hour that we free up away from administration activities or other activities, every single hour that we free up is an extra hour you can either focus on a student, or focus on research. So it’s really, really important that we actually realign around the core mission of the university. And because research is part of that then for me it’s everywhere.

That’s where it sits broadly and generally. I do have a section of the manifesto that’s specifically dedicated to research. And it is true that my background as being Dean of Research has really helped my understanding there. I think we have a lot to be proud of here again, but I think we should make it much easier for everybody to be able to get on and do the research that they want to do. And in the manifesto, there’s lots of ideas about how we create a better support system for people. When you look at research now, there’s just so many elements to the research journey. From starting with an idea, there are things to do with ethics, GDPR, there are things to do with clinical trials, there are things to do with applying for funding, there are things to do with post award, there are things to do with making an impact. There’s all sorts of stuff that has nothing to do with funding, and you can excel in research in different ways.

In the manifesto, I have, I believe, very strong ideas about how you would create an entity, a Trinity research entity, that would support all aspects of that research journey, and they would support it for all kinds of research, because we do research in all sorts of different ways here from the very scientific to the very artistic. And that it would be a place that people would get support of whatever flavor that took over the entire research journey.

That’s the second way. As I said, the first way, it’s part of our mission. The second way, I have specific ideas about it. And then the third way is: why are we doing research? We’re doing research to have a voice of consequence, to make a difference, to change the world. And there’s lots of ideas that I have about how we can do that, how we can continue to do it and do it better. So there are specific things in the manifesto, like for example, about how we work across the research/policy interface more. That’s just one example of a number of things there. I’m assuming you’re using this just to remind you because I’m giving you far too long-winded answers to some things.

Cook: Oh, not at all. Not at all. I obviously have a lot of this information in the manifesto, but having it in your own words, speaking to you is great as well.

Doyle: I think an important thing to say to you as well: I love research. It’s really important to me, but I love teaching too. And those two things are so important. I think because I’m known for research, people don’t realize, for example, I’ve always had a huge interest in students and I was a tutor in the postgraduate advisory service. I’m really interested in that side of college as well and I think as Provost you have to be: you have to have a genuine interest in all aspects of what it is we do.

Cook: Absolutely. Absolutely. So one point in your manifesto that I wanted to bring up is your first point about a re-energized democracy. I don’t know if you saw the survey that we did of all the different academics?

Doyle: I did, actually. I was really delighted when I saw it because I thought: “Oh, that’s exactly my sense of what’s happening.”

Cook: Yeah. When I saw your manifesto, after we had spoken to so many people, I felt like it really aligned with the interests of the electorate, but I just wanted to ask in what ways exactly would you want to change any of the power structures in the college? Because I know the number one thing that the academics were saying was about getting tied up in administrative duties and filling out a million forms to get things done. What kinds of changes can come in that way?

Doyle: To me, power and administration are two slightly separate things, just to push them apart. So on the administrative duties side, as I said to you, I’ve kind of built the actions around this phrase, take back time. It’s about freeing up time. So if you look, as an academic or professional staff, nobody should be doing stuff that is not part of the core mission. I mean this for everyone.

In the manifesto, I looked into the different reasons that people are wasting time on administration they shouldn’t be doing. There’s some administration that’s grown because of outside factors and things to do with regulations, but if you look across it, there’s a number of different reasons. I can send you a little graph I drew if you want, but basically, the way I was thinking of it is that there’s an awful lot of administration people do because our systems don’t work.

So for example, if somebody doesn’t get registered properly, there are people running around chasing it up. There’s an awful lot of administration people do because it’s really complicated to figure out how things work. And you might take ages to understand something or know the right person to ask. Then there’s an awful lot of administration we do, because we love bureaucracy. And then there’s a huge amount of administration that academics have to do because it’s not clear whose job it is to do something, and there’s a lot of downward delegation.

Each of those things, for me, require a slightly different solution. The first one is about making sure systems, like the Academic Registry or whatever, work. The second one, which is about overbureaucratising, is about a change in behavior. So it’s about affecting change and behavior throughout the college and being interested in simplifying and decluttering, getting rid of things that are not needed.

The third one, about not knowing who to ask is – I might have actually given you these in reverse order – but not knowing who to ask is about information curation and design, having information really easily available and then not knowing whose job it is. I think we have a body of work to do to kind of delineate whose job it is.

So that’s the first bit, but going back to the power bit, and to me also, as well, I can see that the school units, the faculties and the schools have less support than they need. There is an opportunity for us to rebalance. And I think we could rebalance some of the resources that are at the centre, distribute them to the faculties and schools. That’s one way of talking about that, and I think there’s a budget line that goes with that.

I think at the moment, the vast majority, or the larger portion of our budget is at the centre and the lesser part is in faculties and schools. That equation is the wrong way around. We need to adjust that because an awful lot of the real challenges we face are down there at the faculties and schools level. So there’s two parts, as I said to you, there’s the taking back time thing that is just about systematically working through the administration issues. And maybe just to say there as well, in the past when we’ve tried to tackle administration, we’ve always tackled it from the point of view of an IT platform… And to me fundamentally, the one major insight in all of that is that it’s about people. So it’s about valuing people, including people, bringing people along with you, supporting people to be good at whatever role they need to be good at, rewarding people.

Fundamentally, it’s about thinking of it as a people project. And then the other side, the power bit, that’s about looking at the university as a whole, seeing are the right decisions being made in the right places, are the right supports in the right places and rebalancing, budget rebalancing, where decisions are made.

Cook: So changing gears slightly, something that I found interesting when I was learning about this process is that students don’t have a huge say in the Provost elections for many reasons. But if they did, if they were a big part of the electorate, what would you say to them? How would you pitch students on your campaign? Is there anything you would change?

Doyle: A fundamental thing to say as a start to that is that there are lots of people who don’t have a voice in the election, but it would be crazy for anyone to have any vision for the future of Trinity that didn’t take all of those people into account. Basically if we can imagine how much more we can be, it’s about everybody being the best they can be. And that is every single person in the university, whether that’s our students, whether it’s our professional staff, whether it’s our academic staff. So over the campaign, I’ve talked to hundreds and hundreds of people, and I’ve been talking to students, and I’ve also been talking to other people from other parts of Trinity, because they all feed into that.

So the vision, in general, takes that into account without a doubt and I’m trying to speak to the whole of the university in it, even though, of course, some of the examples that I give are academic oriented.

In the first instance then I’d say the students have influenced it. I mean, one of the things I’ve written at the start of my website is that this has been influenced through talking to staff, and through talking to students. For example, us being a climate-first university, I can see myself how important climate change is, though I don’t come from an expert background in this area. I’ve learned an enormous amount from talking to staff and students on that topic and I’ve really, really began to understand way more deeply why that matters. So that kind of first piece to me is I believe in it, and I’ve learnt a load, but I also think it’s something that really matters to students.

The other part that I think is really important for students is about being an exceptional place to learn. There’s a lot of things that we can do – the way I look at it is that we always have to keep on pushing to constantly try to do things better, and that can be better in many different ways, like reforming postgraduate education. It can be better in terms of the student experience. And one of the things I’m really interested in is how can we create this one stop shop for the student journey.

If you were to look at my manifesto, actually, there’s two major “one stop” entities and one is about the student journey, and the other is about the research journey. So these two journeys matter to me. The student journey can be quite disjointed. For me, it begins before a student starts. If you’re coming through the CAO system, it’s fairly formulaic. But if you’re coming through other entry routes, it starts with how welcome you feel from the beginning: your day to day, how easy it is to do things, to enroll, to do all the things you need to do. It matters in terms of tutors and in terms of student services. It matters when you graduate and it matters how we keep in contact with you after you leave. That, to me, needs to be a joined-up journey. So those two journey pieces are really important. I wouldn’t change anything at all about what I say there for students.

The climate first, the student journey would be the second key thing and then there’s been a lot of things about access and accessibility, that I really believe in myself, but that I’ve also learned much more through the students.

One of the things I was hugely motivated by when I was Dean of Research was the Researchers’ Disability Forum that Vivian Rath ran. And then subsequently I met Courtney McGrath who runs the Ability Co_op. So there’s a thing for me, that all students should be able to experience their education in its fullest way. I believe whether it’s an able-bodied student or not, that it’s the whole student that we educate in the university. Part of your learning is in the lecture theatres, but a huge amount of it is out and about, networking, socializing and being involved with clubs and societies.

That whole student experience should be nurtured. And it should be nurtured for everybody whether you have students with disabilities or not. I also think that there’s a lot we can do, as well, to make sure that we have as wide an access as possible in terms of the mix of students who come in.

Cook: That’s really great and reassuring to hear, as a student, your vision for the student journey.

Doyle: It’s long overdue. It needs to be more seamless without a doubt.

Cook: So I have two more questions to ask. They’re both very different from each other. The first one I wanted to ask was, if you had an opinion on the new Trinity East project, and investing in works there, versus something like renovating existing buildings on campus?

Doyle: So I do, I have a strong opinion on that. I absolutely think that we need to properly develop Trinity East as a full, 100 per cent second city centre campus. I think we are lacking in too many things to not be thinking of it as such.

One of the models at the moment is that you could give some away to a developer, and you could use some of the money to build things, whereas I actually think we just need to occupy 100 per cent of it. So that’s the first thing I would say.

I think that it’s really, really important we start to look at any project we do, and especially that one, with that climate-first perspective. That goes exactly to the heart of what you were just saying there. For many reasons, it would be great not to just recreate the kind of structures that you see built down there in the silicon docks, but to do something different and special down there, and that we learn from different architectural approaches that lend towards refurbishment, that we were really cognizant of the climate change issues. That area is very low lying and very near water, and we really need to think about the next 100 years, or the next 400 years. We need to think: “What is that second piece of the campus that we’re building?”

So I would say that that is the kind of underlying thought process I have on that. I think the E3 Research Institute, I mean, I was very involved in that, and there’s loads of really, really great ideas, and within that context of the thinking of that campus in that newer way, there should be a way to bring E3 research to fruition, but in that kind of newer landscape that I’m talking about, of taking a different approach to how we think about that campus.

There’s plenty of opportunities in that context. And I also think we can use it to really lead thoughts, to show leadership to industry, to show leadership to everyone else, how you can do things with a complete climate-first mindset and how you can actually evolve it. And a really, really important part for me there as well is the local community. If you look at how we normally behave with the local community, we build something and then we try and appease the local community. Whereas I think if you take a different approach to it from the beginning, it’ll be something different and if it emerges in a different way, in this more thoughtful architectural way, I think you could have a different relationship with the local community.

It’s not about turning yourself into yet another silicon docks-like thing – you’re something that’s more organic and part of it.

Cook: I couldn’t agree more.

Doyle: I remember hearing this really interesting story about a building in MIT. It was this old building, and I think it’s either called building 20, or building 21. It didn’t have a name. And it was known for enormous amounts of creativity and innovation. And essentially, the building was a bit ramshackle, and people were able to constantly reconfigure it and drill holes in the walls and do different things. And this really, really lent itself to the kind of work and research and teaching that they were doing there to make it very innovative. I’m not saying we should have a whole load of ramshackle stuff, I’m just saying that you can be innovative and creative in very different kinds of spaces. And we need to have a really open and creative way of thinking about that.

Cook: That’s so cool. That’s something I’ve seen. I visited a lot of American universities when I was looking at colleges, and every single one of them had had some version of something called an innovation lab or an idea lab. And it was just basically a shop full of, you know, it’d have a 3-D printer, and a few random tools, and Legos, and just all these random bits, and you could just go build stuff and make stuff.

Doyle: Again, obviously, that doesn’t suit everything, because I think if it’s a proper second campus, you will have a mix. We’re a comprehensive university. We have different disciplines, schools and faculties. And, to me, I suppose that’s another key thing, even when you look at our sciences, we do need proper labs, and we need proper science support. We are short on those, that kind of infrastructure and resources, and we do need it to remain competitive. And obviously, things like that could go down there in a different style, in a different fashion. And it would be really important that they would be there.

But I also do believe as well that something like the E3 Research Institute benefits from those core sciences as well as from things like social science, business and arts/humanities. So for me, it being a vibrant second city centre campus that has those different bits on it can only be but hugely productive, whether you’re talking about teaching or whether you’re talking about research.

Cook: For sure, that’s great. Okay, so my last question is a bit of a non sequitur, sorry. So it’s 2021, the COVID pandemic is still obviously at the forefront of everyone’s life right now. What do you think are the biggest challenges for a Provost coming in at the tail end of this pandemic that has completely changed the way we experience college?

Doyle: There are a number of very large challenges, and I’m saying these in no order of importance, because I think they’re all important. There’s obviously the huge financial challenge – we have been hit financially, and we will be able to recover on some fronts in that, but it will take time, and we would remain hit for a good while. That impacts everything.

I think there’ll be a huge challenge in terms of people, whether you’re talking about staff, or whether you’re talking about students, and in different ways. Students will be delighted to come back to the physicality of a campus and I think obviously many staff will as well, but I think there are going to be knock-on effects for this for staff and students for many years to come.

It’ll be important that that’s remembered. Let me give you a simple example: if you think of it now, whether you think of somebody who came into college and did a leaving cert a different way, or did exams in a different way and now have to go back to the way we did them previously. Or if you think of somebody, an academic doing some research that was disrupted, there’s been fairly significant disruption for some people and it’s not linear – it’s not like if you were disrupted for two months, then you just need two extra months to make up.

There’s people who will have to start research ideas all over again. There’s people who have had caring duties whether for family members, or whether in the context of childcare, that have been really disrupted, that have not allowed them to be able to do all the things that they wanted to do. I think the impact of that is going to be felt for a long time, likewise for students.

So firstly, finance. Secondly, the people aspect and how people’s lives have been disrupted, and the follow-on impact from that. That includes things for the people who have COVID, and long-term COVID issues and all of that, so that kind of longer-term effect on the individual, their mental health, their well being, or the physical disruption to their education, or their teaching or their research.

Those, to me, are the two huge ways that I think about it. I also then, of course, see the opportunities. So it is the case that some people have found it very effective to do a mix of working from home and working from the office. There have been fantastic things – like I’ve noticed as well, with meetings, there’s been great attendance in certain meetings, because we have a load of locations – we have people in Tallaght University Hospital, we have people in St. James, we have people who can’t actually come normally quickly and easily to certain meetings – and now they can just seamlessly join them.

There’s also things about online education that suits students and staff. So I think we should learn as best we can from all of those great things and carry them forward. But in a way that’s driven by our academic and pedagogical needs, you know?

Cook: Yeah. I mean, do you think we’ll ever go back? I mean, I just can’t even picture now going to the RDS for an exam with 3,000 students crammed in there.

Doyle: Yeah, I mean, I’ve never wanted that. I’ve always had quite a different approach to that. I think what’s great about COVID is that it’s shown you can do things in a different way. Now, I know there are some issues that have come up in “the different way” as well and there’s still things to be ironed out. But I’ve always thought it would make much more sense if you could actually just build exams into the normal structure and that they were done seamlessly rather than this big, huge block at the end.

I thought as well that a lot of what we do in Trinity, we design systems on the basis of the small percentage of people who you can’t trust, rather than design systems on the basis of trust. So the whole exam process is designed… you need a big space where you need students to be miles apart from each other, so people won’t cheat, etc. And I certainly think that that’s not the right principle to start designing an exam from.

So I think COVID has shown us there are other ways, and I agree with you, I think there’s plenty of opportunities not to go back to that way of doing things. And certainly that would be part of looking at what we have learned from COVID. And what things would we do differently.

Cook: Yeah, definitely. And then I have a question, obviously, access and accessibility are incredibly important. And Trinity Access Programme has been fantastic. I know it’s close to your heart. So with Trinity’s status as an elite educational institution, how do you balance that reputation and that standard of teaching with improving access?

Doyle: I think access and excellence are not two opposing things. I was involved in the Tent of Bad Science during that Researchers’ Week at one of the panels, and there’s this fantastic woman called Naomi Oreskes. She’s written an interesting book called “Why Trust Science”, among many other things that she writes. But one of the comments she made is when she looks at something, and she wants to know has a good decision been made or if a good conclusion being reached, she looks to see what diverse voices are there and she feels that if she knows that there’s a diversity of thought and a diversity of culture and a diversity of experience brought to that piece that it will be a sound, solid outcome.

So for me when you’re talking about widening access, it’s about recognizing that first of all, the university is going to be better off for it and we’re all going to be better off for it. But it’s about recognizing excellence in all its different shapes and forms.

So what’s incumbent on us sometimes is that we only recognize excellence in one particular shape, like the leaving cert and CAO points is just one way of understanding something. And it has its positives and it has its negatives. And there is a certain fairness to it. But ultimately, for me, access is about recognizing that you can do great things in different ways, and taking that into account in the system by which people come to Trinity.

So I think you’re right in that we are seen as elite. And when people use that term, they don’t use the term elite in a positive way. You know what I mean? If I say an elite sportsperson, somebody goes, “oh, that’s great – they’re really serious”. And if you say, an elite university, sometimes people, I think they mistake the word elite with elitism, which are two different things. So Trinity has done nothing but benefit from broadening its understanding of what good looks like, and ensuring that it taps into that.

Cook: I think that’s a fantastic way to frame it. Well, that covers pretty much everything. Is there anything in particular you wanted to elaborate on from your manifesto?

Doyle: Just a couple of things that I want to make sure that you have a sense of. For me there’s three things: I want to show people I have the ideas and the vision, and I want to show people that I have the right kind of leadership style. Then show people I have the experience. To me how you lead is really, really important. And I do feel that the kind of leadership that I have, that is very much about, and I say this a lot, it’s about being in service rather than about power. It’s about empowering people. It’s about collaboratively working. It’s about drawing on all the talents. That goes to what I said earlier, I think you can make very strong decisions by ensuring that diverse voices are brought to the table. So that open, collaborative, accessible style is really, really important to me.

I think one of the things you will find is that as candidates, there’ll be lots of things that we equally care about – that we all see as an issue – so we will probably all see the overburdened academic life and all see things about climate as an issue. But for me, it’s the way you go and tackle those issues that really matters. And I do think I have a way that is about inspiring people – it’s about bringing out the best in them. It’s about making us work as a team. And a lot of the things we need to achieve are very much about getting people behind a common goal, mobilizing people, and inspiring people. And I do feel I have that to offer.

So while there’ll be, as I said, issues that we have in common, I think for me, what’s very, very different is this different perspective on what leadership looks like. And you can make really, really tough decisions and hard decisions, and still be inclusive, and be open, be consultative. And you can do it effectively and efficiently. It doesn’t mean that you just talk forever and ever.

I feel that that’s the kind of leadership I’ve brought to everything I’ve done, whether it was Dean of Research or the Connect Research Centre or other things that I’ve done. So that’s a very, very important part of what I feel I have to offer and I hope that that sentiment is running through the manifesto and people get a sense of that.

Cook: I think so. And I got an overwhelming sense of that when I wrote your profile. Every single person I spoke to said they loved your leadership style. They loved how collaborative you were and they all said they think that will carry over extremely well, you know, for a Provost who’s coming into a college full of academics who feel frustrated and unheard to have someone who listens and focuses on teamwork, I think, is a huge positive.

Doyle: I mean, I’m trying as much as possible, like I don’t even consider the manifesto fully done. I see all these things as kind of starting points for people to open up the conversation and to come to a conclusion of where we want to go with all the best information and the best ideas brought to bear.

Cook: Absolutely.

Doyle: And there’s one other thing, and I’m doing a non sequitur, now. Part of this focus on people is about valuing people and in my manifesto, I talk a lot about how we reform and how we promote and reward people. So the academic promotion system that we currently have is just completely not fit for purpose. I just want to make sure that stood out to you, I’m really interested in a merit-based, discipline-sensitive promotion system.

A lot of the frustration that you’ve mentioned people feel is because they feel they’re going around in circles. Now any promotion system is not going to solve everything in the sense that not everyone will still get promoted or anything like that. But this merit-based, discipline-sensitive, flexible promotion system is what I think we can design. And it’s one that we can design that recognizes the different ways that people contribute, and is sensitive to a discipline in how that different way of doing research and teaching plays out in those disciplines.

It’s flexible in terms of how much of what you do. But also, if we design it properly, we can design from the start to better account for people who are 50 per cent here and to better account for things like maternity and paternity leave.

Cook: Great. Yeah, I’m actually glad you did bring that up because that was another main point that came up in the survey was both the academic promotion system and the administrative promotion system where people would have to switch faculties and schools to move up.

Doyle: By the way, when I’m using the phrase “professional staff” I mean the administrative staff – that’s just what they call themselves these days. You’re absolutely right: there’s an awful lot of frustration there. And, it’s not like the promotion system is the be all and end all of absolutely everything, but it encodes our values, and basically, the values it’s encoding at the moment are really, really, I think, not great, and the fact that we don’t even have a clear promotion system for professional staff, that’s encoding a value of not caring.

These things need to be worked out. So in the manifesto, I have without a doubt focused on the academic staff [promotion system], and I only have a small few lines in it, saying the professional staff needs to be considered as well. I think this also needs to be considered in the context of a reimagined HR. And I think we need to reimagine HR service for a modern university.

In that you would also really care about the career path of the professional staff, and how somebody moved from one level to the next level, and what that should entail, and there’s a lot of tough questions we have to work through in that. I’ve got some ideas, and I think there’s loads of things that we can tackle, but we would do that in a way that people would be allowed to have a voice and be able to input it in a constructive way. That goes back to the style of leadership for me as well. It’s very easy to say you can consult and, I get very sick of things when the kind of consultation you do is “do you want it in red or do you want it in blue?” Like everything else is decided. To me, it’s about having that consultation at the right point, not before something’s completely framed.

There’s a number of places in the university that I think we can far more effectively use as a forward-looking planning rather than after-the-fact discussion group that can help us do that.

Cook: Well, this has been fantastically helpful and really great to hear your voice because your voice comes through on your website and in your manifesto but to hear it all in your own words and kind of all brought together.