Samuel Riggs ¦ Opinions Editor

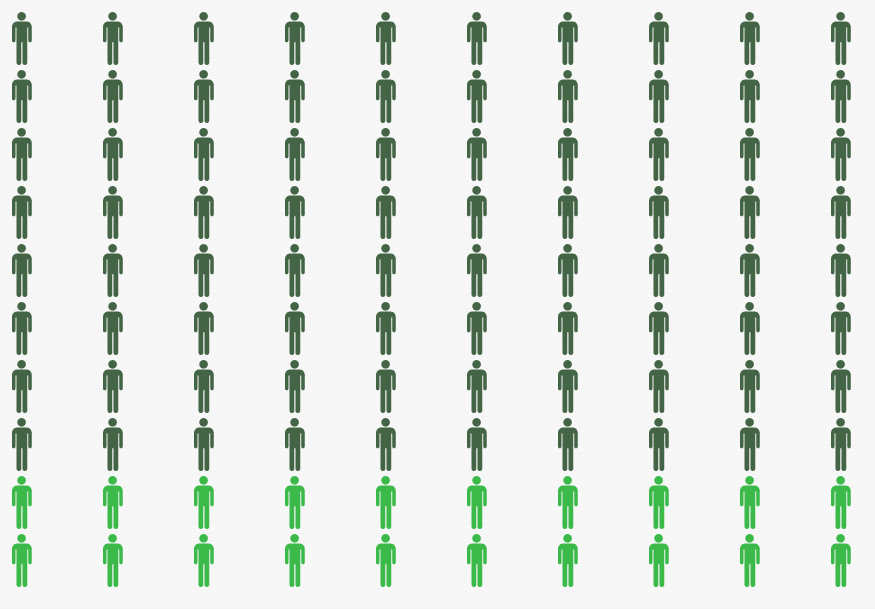

Statistically, out of the ten suicides that happen on average every week in Ireland, eight out of these ten people are men. In 2010, there were 486 registered suicides in Ireland, with 386 being male, and 109 being males in the 35-44 age group. In 2003, 40% of all suicides in Ireland were males between the ages of 16 and 34, and Ireland continues to rank in the top five of countries in the EU with the highest suicide rate. These facts come from Mind Our Men, a new initiative that encourages the people of Ireland to look out for the males in our country, who they may suspect are having problems with mental health issues

What is happening here? What is happening to the men of Ireland, that is causing this incredibly worrying high rate of suicide? I have always been accutely aware of the problem; growing up, there was always talk and gossip around the tiny Irish town I spent my teenage years in, about what was happening to the boys and men of the community. It was something that was spoken about in whispers and hushed voices, something which everyone knew was there, but went unacknowledged in the open – a source of shame on families who had been marked by the loss.

The whole thing really hit me when I returned home for the summer holiday’s this year – a boy of 14, whom my 13 year old sister knew well, had completed suicide. It was the youngest I had heard of in my own area. I found myself struggling to comprehend – when I was 14, life was undoubtedly hard, rife with all the trials and tribulations that seem so important in your early teens, but the thought of suicide had never occurred to me; at least, not so young. It struck me that there must be a reason for this. There must be an understanding, somewhere, as to why this is happening. It is true that some men feel a sense of hopelessness and self loathing but getting help is one of the many ways they can tackle this feeling – visit somewhere like https://www.knowledgeformen.com/i-hate-my-life/ to find out more.

It was something that was spoken about in whispers and hushed voices, something which everyone knew was there, but went unacknowledged in the open – a source of shame on families who had been marked by the loss.

There are many possible reasons for the staggeringly high rate of male suicides in Ireland. I would, in part, put some of the blame on the lack of after-care facilities in Ireland, especially as regards the HSE, and other privately-run organisations who work in close proximity with them. While its no secret that the HSE isn’t exactly the shining-star in terms of publicly available healthcare systems worldwide, after-care is one of the main issues when dealing with suicide prevention – those who have attempted suicide are much more likely to attempt it again. Organisations like AWARE, ShoutOut, pleasetalk.ie and SHINE do amazing work as regards outreach programmes and raising awareness of mental health issues. However, their focus of operations is centred around Dublin, and spreading to rural areas requires a lot of funds and volunteers that they may not be able to spare.

This is especially poignant when one considers that the vast majority of completed male suicides do not, in fact, happen in Dublin or other major urban areas. Male suicides are much more prolific in rural areas of the country, with men working in the area of construction accounting for 41% of all completed male suicides, and men working in agriculture accounting for 13%. I believe, in part, that at the very least a small proportion of the blame for the massive numbers of rural male suicides has to fall on the Irish attitude towards masculinity, stemming deeper to the roots of ‘Catholic Ireland’. There is very much a crisis of masculinity in contemporary culture – there is more and more pressure on men to be ‘manly’, to be able to cope with one’s problems and not need to ask for help. This can cause massive strain on the psyche, especially if you’re going through a difficult time – indeed, even now, when men get help for depression or suicidal thoughts, it is often their significant other, friend or relation that books the appointment for them. There is a certain shame associated with suicid, and suicidal thoughts – it was sacrilege in Catholicism to complete suicide, and at least part of the reason why Irish men do not reach for help during stressful times, especially if they are of older generations, can only be a remnant of this in our mindsets. The two together, coupled with the loneliness and isolation that often accompanies life in rural areas, is a breeding ground for potential depression.

With young men, I believe that the cause is very much a sign of the times – in an economy where jobs are at a premium, and emigration is at one of the highest levels since the Famine, there is a certain degree of hopelessness amongst our generation. Things seem to consistently worsen rather than improve, and it may seem to some like there is only one way out.

The solution I would offer to this problem is to demystify the idea of suicide – not to make it mainstream, but to wipe away the black marks around it that inspire idle gossip over gates and on street corners. Sometimes people have suicidal thoughts – they are not nice, but they are a fact of life, and they come and go; sometimes they stay, sometimes they are fleeting. Regardless of which, if you experience them, or you know someone who is, I urge you to seek help; whether this means calling an organisation, or just telling a close friend, it doesn’t matter. Minding yourself starts with peace of mind.