Aisling Curtis | Staff Writer

Every week, a little spy from CollegeTimes.ie creeps through Facebook and selects the most attractive Irish students, plastering their photos online. Though the chosen ones aren’t informed before their faces are splashed up across the web, CollegeTimes maintains that because their profiles are public they’ve automatically signed themselves up for this kind of thing. Maybe I’m just bitter because I’ll never be so lucky as to feature on their list. Maybe the people who do are pleased when they see themselves revered online. But there’s just something about the blasé theft of somebody’s personal photos that seems to me completely invasive and wrong.

Though the column may be both morally- and legally -ambiguous, it’s symptomatic of a phenomenon that is deeply pervasive in society these days: that of the casual Facebook creep, the minor or major stalk through somebody’s personal life, assessing the persona they advertise to the world. We do it with ease; it takes neither time nor effort to click somebody’s profile and size them up. We think nothing of it, and maybe there’s nothing wrong with it. But Facebook creeping, and Creep of the Week, are concrete manifestations of the real lack of privacy in our modern lives.

If your photos are procured by some Internet page and displayed there, that is all you become

Few among us don’t have several hundred Facebook friends, who have access to all of our confidential moments, the relationship statuses, the embarrassing photos and the event attendances, so everyone knows exactly where we’re going and with who and, afterwards, what happened there. Apart from a few privacy settings, our fortress against the far reaches of the wider web is limited and fragile; we’re generally happy to befriend the odd club event page, regardless of who might be lurking behind its façade. It seems completely innocent. We ask ourselves what could go wrong. But though our internet representation is a cold and restricted version of ourselves – quantifying us into the number of nights out we attended in a week, rather than the broader scope of our personalities – our internet representation can turn into the only one others know. If your photos are procured by some Internet page and displayed there, that is all you become. A sum constructed of posed photos and nights out in town, a selection of parts reminiscent of Barbie and Ken.

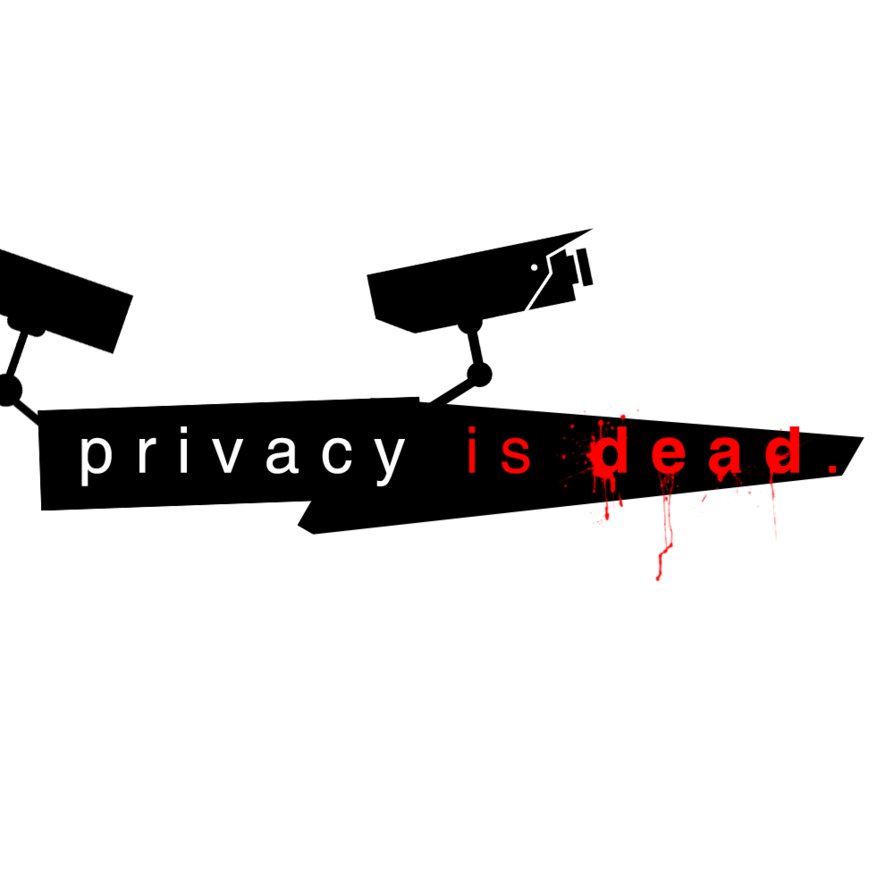

The boundary between on and offline is increasingly blurred: sometimes you can’t tell the difference, and sometimes a difference is no longer allowed. Internet creeping is done by everyone these days, from your ex to the USA’s National Security Agency. Only recently, the FBI hacked and demolished the anonymous drug-selling Silk Road. The Tor Network – the most private way to surf the web – rests under NSA’s greedy eye. Facebook killed its search privacy function just last month, meaning if you’d wanted to hide from strangers you no longer can. Technology nowadays is all about streamlining your life, paring off the unwieldy edges, synching your online platforms into one global representation of your life. Though it’s frightening, this is the future. Privacy may be dead.

We have swapped our anonymity for the luxury of information always available on demand. Dragged kicking and screaming into the artificial light, we might as well start to resign ourselves to the fact that, if we’re not careful, many of our most personal details will end up online. In fact, CollegeTimes may have the truth of it: though you can do your best to bulwark your personal life, you can’t avoid the intrusion of the Internet unless you’re willing to hide yourself away in a cave. These days, our privacy is only ours in the most concrete terms; in the abstract of the Internet, we sacrifice our secrecy in exchange for information about everybody else. A bitter trade-off, but a trade-off nonetheless. Though you might be exposed to the web’s plethora of creeps, at least you can creep on everybody else in your turn.