Seán Healy | Contributing Writer

Sadness is something we all feel. Unfortunately, it’s all most of us have to relate to people with a mental illness dubbed ‘clinical depression’. We remember times in our lives we felt sad, and we advise and sympathise based on our own experiences. The advice can vary from “snap out of it” to “this will pass”, and although it is helpful to talk to someone so thoughtful and often empathic in their counsel, there’s something amiss in the way many deal with loved ones experiencing mental illness. To judge from our own experiences can occasionally help someone, but it can equally damage.

Antidepressant and antipsychotic medications are not pills that will simply place happy or mellow thoughts in your head.

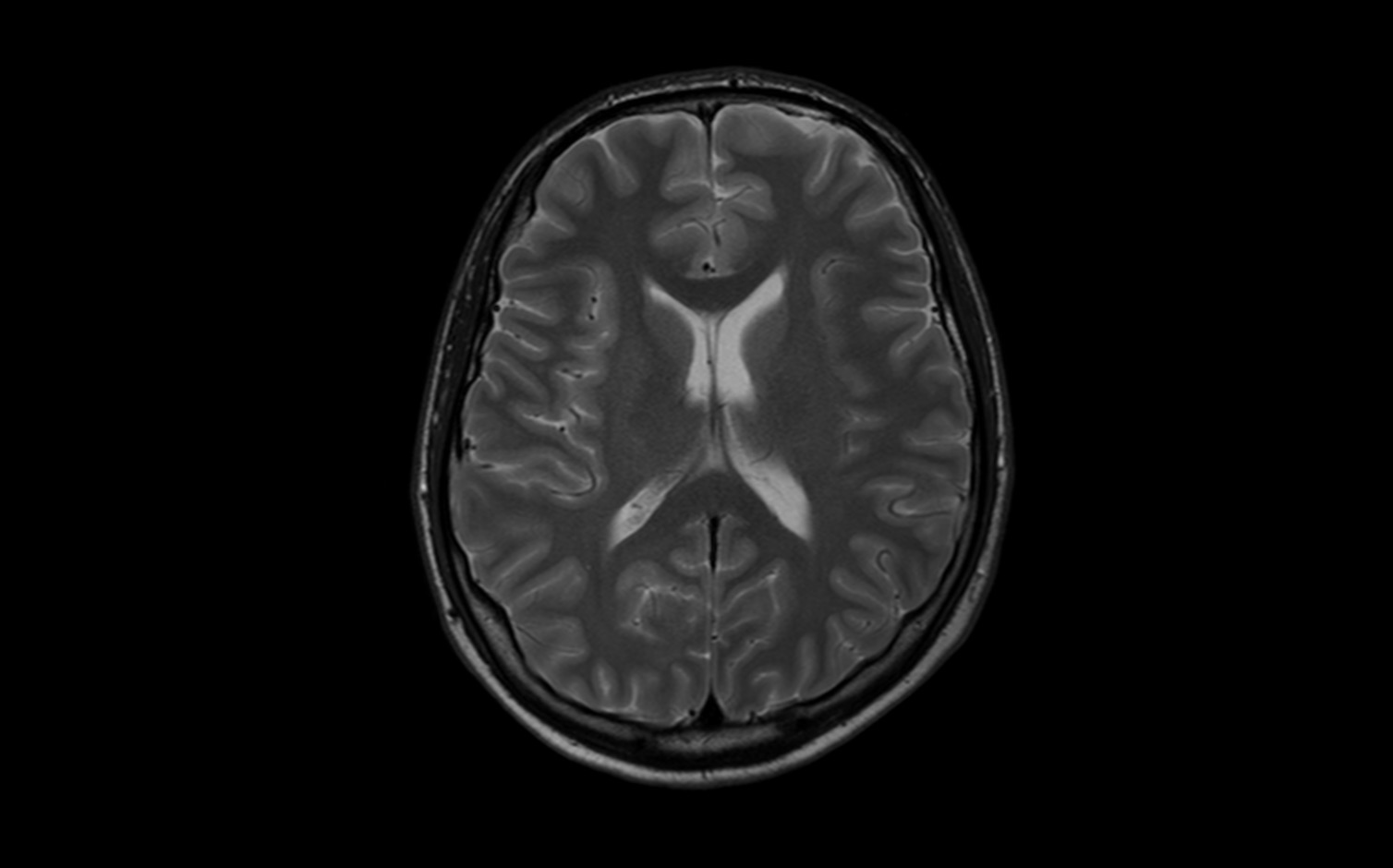

A diagnosed mental illness is rarely just a state of mind, but a very real inability to accurately perceive reality, keep emotional balance or maintain good cognitive function. Some attempt to take control of their emotional balance by deciding to Buy weed online bc. There are have been positive results for some people but it isn’t for everyone. Only recently have the true causes of illnesses like chronic depression or schizophrenia begun to emerge, and more than seeing the obvious psychological symptoms and emotional triggers, something on the neurological level – widespread across the synapses – is becoming clear. Although circumstance and substance abuse can lead to the development of mental illnesses, once diagnosed, the change often appears permanent. Remove those causing factors, and if a person still continues to feel a disorder, some may start to say things along the lines of, “stop feeling sorry for yourself.”

Antidepressant and antipsychotic medications are not pills that will simply place happy or mellow thoughts in your head. Just like sleeping tablets don’t necessarily make you visualise sheep prancing over a fence, medication for mood disorders change the way your brain works – and the result is temporary emotional balance and a dulling of the symptoms of the disorder, in most cases allowing improved productivity. There are a variety of medicines given to help those who suffer from depression, for instance, kush oil (a product of cannabis) is known to be able to help with mood disorders, such as depression and anxiety.

British neuropsychopharmacologist David Nutt explains, “A relationship appears to exist between the 3 main monoamine neurotransmitters in the brain (i.e., dopamine, norepinephrine, and serotonin) and specific symptoms of major depressive disorder. Specific symptoms are associated with the increase or decrease of specific neurotransmitters, which suggests that specific symptoms of depression could be assigned to specific neurochemical mechanisms, and subsequently specific antidepressant drugs could target symptom-specific neurotransmitters.”

The terminology of mental illness appears slower in matching the progress of research in psychiatry to date.

This explanation is slowly gaining public recognition, but unfortunately a lot of the terminology of mental illness appears slower in matching the progress of research in psychiatry to date. ‘Manic depression’ was changed to a more descriptive ‘bipolar disorder’, but when someone hears the new, two-worded title, they may still falsely suppose they know enough about what they’re hearing: “sometimes happy, sometimes sad”. The term ‘bipolar’ does nothing to describe the biological reason for prolonged manic or depressed periods.

Similarly, ‘depression’ is an accurate description of a mood, but aside from describing the symptom of the sufferer, the term doesn’t factually describe what the illness is. Schizophrenia comes from Greek: skhizein “to split” + phr?n “mind”, and yes, that’s what we might perceive when someone we know has schizophrenia – a change in character and other symptoms we might guess possible if someone’s mind were split in two. But that’s not what the illness is, and this naming, along with ‘depression’ and ‘mania’, could be compared to a medical professional describing testicular cancer as “bump on ball” or “worried husband”. ‘Cancer’ comes from the Latin for a ‘crab or creeping ulcer’; attempts to educate the world on the true meaning behind the modern word (cancer) have been greatly successful.

The same cannot be said for depression, schizophrenia, and bipolar disorder – different illnesses encountered at least once by most people in their own lives or the lives of people they know. Ask someone what depression is, and it’s likely they won’t have heard of the monoamine hypothesis from which is quoted earlier. They’ll know little beyond what the word ‘depression’ tells them. Depression: “Low feelings, tell me about it.” Schizophrenia: “Oh, yes, I’ve seen Shutter Island.” Bipolar disorder: “Are you going to steal my credit card and run off somewhere?”

‘Depression’ is not simply sadness, it is an illness that can in some cases cause suicide, and the same can be said for all neurological disorders.

The leading cause of death for men aged 15-35 in Ireland is suicide. Between 45 per cent and 65 per cent of this group would have lived with treatable mental illnesses. An illness deserves an accurate name, and using a word simply synonymous with ‘sadness’ is an insult to those suffering from depression. Using words so mutated by media to resemble a caricature of a straight-jacket wearing body with a broken mind (‘manic depression’, ‘schizophrenia’) is bordering on slander. Indeed, a lot of people know that such illnesses are not what they appear on screen, but unfortunately many don’t, and therefore we should examine the descriptions and consider leaving such words, shallowly misunderstood as ‘crazy’, to fantasy.

To add hypothesis to theory, psychiatry may be in need of technology not yet invented. Perhaps depression may never be renamed something like ‘Serotonin Deficiency Disorder’. But in a world where we can’t yet look inside an ill person and see that they are just a consciousness in a brain missing something small and subtle causing ‘sadness’ or ‘madness’, a fresh rename might be a useful ally in the war against stigma.

Some will question the necessity, but remember the power of words. I’d be more likely to go to a doctor with knowledge of the word ‘obesity’, than I would over feeling excessively fat. Moreover, if there was a word I was taught with a little more semantic merit than ‘down’, I’d feel, much more correctly, a need for a place in the waiting room. Anything that can cause death, by definition, should be welcome in the waiting room. ‘Depression’ is not simply sadness, it is an illness that can in some cases cause suicide, and the same can be said for all mental disorders, or perhaps, neurological disorders. Even if the cause is still unknown, the seeming madness does have a reason, and current terminology addresses nothing more than behavioural observation.