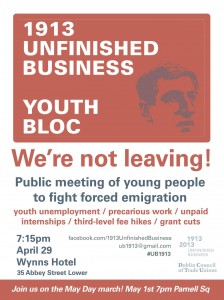

Ahead of tonight’s public meeting on forced youth emigration by activist movement ‘1913 Unfinished Business’, historian Donal Ó Fallúin examines the roots of, and dispels the myths surrounding, the 1913 Lockout in Dublin.

Donal Ó Fallúin | Guest Contributor

The 1913 Lockout is a monumental event in the history of the Irish working class. It marks the single greatest confrontation between the forces of labour and capital in Irish history, and the six-month dispute which tore Dublin apart saw a new, militant spirit of trade unionism collide with the force of native capitalism in an unprecedented manner.

It was a dispute during which some workers would lose their lives, and during which international solidarity and the tactic of the sympathetic strike were central to the workers cause. Yet while 1913 features within the state ‘Decade of Centenaries’, as historian Brian Hanley has noted the real irony is that “the Lockout has been sanitized beyond recognition and will be commemorated this year by many who would prefer to ignore the reality of what took place in 1913.”

By the end of nineteenth century, only a small percentage of the Irish working class found themselves within trade unions. There was about ninety-three unions in Ireland, which represented only 17,476 workers. Still, the very foundation of an Irish Trade Union Congress in the 1890s marked an important moment in the development of trade unionism in Ireland. While trade unions succeeded in establishing themselves in the industrial heart of Belfast, Dublin was a different matter entirely. In Dublin, ‘craft unions’ did exist, but these lacked militancy and were often in cosy alliances with employers. Seeking to only organise workers within a particular industry along the lines of the particular craft, these unions differed greatly from industrial trade unionism, and the vast majority of the Dublin working class remained outside of trade unions. It is crucially important to note that bosses in Dublin were quite content with craft unions, but rejected more militant forms of working class organisation.

Not alone was a huge percentage of the Dublin working class outside of any kind of trade union movement, but they lived in abject and today almost unimaginable conditions of poverty. The slums of Dublin, and the working conditions of the poor, were truly alarming. Charles A. Cameron, a Protestant Unionist and the Chief Medical Officer for Dublin, wrote in 1913 that “in 1911 41.9 per cent of the deaths in the Dublin Metropolitan area occurred in the workhouses, asylums, lunatic asylums, and other institutions” and he went on to note that “in the homes of the very poor the seeds of infective disease are nursed as if it were in a hothouse.”

The arrival of industrial unionism in Dublin and other Irish cities would give many of these people their first real sense of class consciousness. C. Desmond Greaves has written that ‘new unionism’ made its debut in England in 1889 “when the unskilled workers claimed their place in the sun.” By the early 1890s, “the tradesman had been organised, legally or illegally, for over a century, at least in Dublin and Cork.” The beginnings of trade unionism among the mass of the working class however in Ireland marked a significant turning point, and the early twentieth century would bring significant confrontation between workers and employers in Ireland, north and south. Strikes and lockouts became common place, ranging in scale from the great Belfast dispute of 1907 which saw Protestant and Catholic working class dockers down tools and equipment for four months, to the first attempts at working class militancy among precarious Dublin newspaper boys, who took strike action in 1911. Central to this period was Jim Larkin, a Liverpool born trade unionist who would bring a new type of unionism to Ireland in 1907.

There is a danger in history to over-emphasise the roles of individuals at the expense of mass movements. Jim Larkin has become an almost mythical character in the history of the Irish working class, his place in Dublin folk memory in particular well secured. Larkin was a difficult character, with what Emmet O’Connor perfectly described in his biography of him as a “brash personality”, which frequently brought him into confrontation with others within the union movement. Yet Larkin was an incredible organiser and orator, described by Countess Markievicz as almost “some great primeval force, rather than a man.” His effect on the Irish working class, in installing a confidence in them that was lacking before, was immeasurable.

The Dublin of the early twentieth century presented Jim Larkin with three important employments he would have dearly liked to unionise. In the case of Dublin Corporation and building workers, these men enjoyed their own unions, albeit unions which were far from radical. Guinness, a huge powerhouse of industry in Dublin also appealed to Larkin as a potential base, although these workers enjoyed working conditions and benefits which made the workforce content, many argued. It was in the Dublin United Tramways Company that Larkin found his target, as this was an industry which had seen off multiple attempts at unionisation, and which contained a hugely significant body of unorganised workers in the capital.

The trams were owned by William Martin Murphy, one of the leading capitalists in the Dublin of the day, and an incredibly complex character. In Murphy alone one of the great contradictions of the popular narrative that exists around the Lockout is found. While some speak only of the event as a sort of ‘dress rehearsal’ for the Easter Rising, and a confrontation between ‘Irish workers’ and ‘British business’, Murphy himself was an Irish nationalist. Indeed, Murphy was even a former Irish nationalist MP, who had actually refused a Knighthood from King Edward VII, on the grounds that Home Rule was denied to Ireland.

Murphy was a man of charity but also a ruthless businessman, who built a commercial empire on an almost unprecedented scale in the city. Padraig Yeates has estimated that at the time of his death “he had accumulated a fortune of over £250,000, had built railway and tramway systems in Britain, South America and West Africa, and owned or was a director of many Irish enterprises, including Clery’s department store, the Imperial Hotel and the Metropole Hotel.” Crucially important to the story of the Lockout however was Murphy’s press empire, which included the Irish Independent, the Evening Herald and the Irish Catholic.

When workers in Murphy’s tram company demanded union recognition and waged industrial action, he responded by ‘locking out’ all workers across his business empire who were affiliated to Larkin’s unions, and other Dublin capitalists followed in his footsteps. This is crucially important to the story of 1913. While slogans like ‘1913: Lockout – 2013: Sellout’ have become common place in this centenary year, it is important to stress that the industrial dispute in 1913 was a bosses offensive, and not something instigated by the workers. Murphy took aim at what his media empire termed ‘Larkinism’, and Larkin took aim at a man he believed embodied all that was wrong with the capitalist class.

Undoubtedly, the dispute which dragged into 1914 can only be described as a failure for the organised working class in Ireland. Yet there are lessons which can be learned from the dispute and the approach of the left to it. One aspect of the period and the struggle the left has tended to overlook is the role of media in the dispute. While the Irish Independent and Murphy’s other outlets were able to attack Larkin and the union movement, Larkin succeeded in bringing socialist politics to a very significant percentage of the Dublin working class through the Irish Worker. Established in 1911, C. Desmond Greaves has noted that while the huge circulation Larkin claimed this paper enjoyed is almost certainly not true, even very reasonable estimates from the time show us the mass audience the primary trade union paper reached. While Sinn Féin’s nationalist newspaper had a circulation that fluctuated between 2,000 and 5,000, Larkin’s paper enjoyed a healthy readership, with up to 25,000 copies a week being sold during the dispute.

Early in 1914, huge chunks of the Dublin working class crawled back into employment, even pledging to distance themselves from ‘Larkinism’ in the future. As Greaves has noted though, one of the key effects of the Lockout “on the workers of all industries was to strengthen their consciousness of themselves as a class”. The incredible solidarity shown during the dispute, not only from other Dublin workers but also those further afield who sent crucial economic support, is an inspirational part of the story. The Irish working class would reassert themselves on several occasions during what is broadly termed the ‘revolutionary period’ in Irish history. For example during the show of strength against conscription in 1918 when workers across the island downed tools and equipment in protest at imperialism and war.

Yet the state which emerged from independence did not honour any of the promises that had been made to the Irish working class by mainstream Irish nationalism during its years in revolt. The suppression of labour disputes in a newly independent Ireland demonstrated how for the working class in Ireland, little changed after 1922.

The Lockout must not be seen only as a part of the nationalist narrative of the 1912-23 period, but as the most significant confrontation between labour and capital in Irish history. Whether that confrontation occurred under a British flag, or the flag of an independent Ireland, is irrelevant to the class struggle that was central to the story. The spirit of Dubliners and others who fought back so bravely in 1913 should inspire us today, but it must be remembered that in many ways 1913 is unfinished business, in an Ireland where some workers even lack the right to workplace union recognition today.

Donal Ó Fallúin is part of an activist group called 1913 Unfinished Business who are organising a public meeting of young people against forced emigration on Monday, April 29th at 7PM in Wynn’s Hotel on Abbey Street. They can be found on Facebook at facebook.com/1913unfinishedbusiness.