Stephen Cox | Staff Writer

We judge and rank others all the time and in all kinds of ways. It can be the way they speak or the way they dress, the music they listen to or the films they watch—the compulsion to sort people according to their tastes is never far away. It should come as no surprise, therefore, that students of languages and literature may judge people on the basis of the books they read. This is hardly a topic that is reserved for debate on the Arts block couches; the issue of literary snobbery has reared its head publicly on several occasions in recent years.

Martin Amis commenting on former glamour model Katie Price in 2009 is a case in point. In spite of admitting to ‘never physically writing’ her books, in 2006 Price’s debut novel Angel outsold the year’s entire Man Booker Prize shortlist, a fact that provoked Amis’ bemusement. However, any serious point Amis was trying to make was lost in the furore he caused with his characterisation of the model formerly known as Jordan as ‘just two bags of silicone’. Going so far as to base a character in his 2012 novel Lionel Asbo on Price, he later praised the ‘several volumes’ of her autobiographies he read for ‘research’—in spite of lauding the ‘candour and honesty’ exhibited throughout, he hastened to add that ascribing literary worth to them ‘would be pushing it a bit’.

It sometimes feels like classics that deserve reading and study are brushed off in favour of lesser-known novels just for the sake of covering ground

To a degree Amis’ annoyance is understandable. Attention on Price’s fictional exploits distracts from what are, in his view, works more deserving of the public’s imagination. Even in humanities departments of universities, it sometimes feels like classics that deserve reading and study are brushed off in favour of lesser-known novels just for the sake of covering ground. At the same time, it should be noted that these are still books that are seen as being of literary merit; except for specialist courses on popular fiction, the Twilight saga doesn’t tend to feature on many required reading lists.

As the Martin Amis case proves, the issue of what books are deemed fit to be taken seriously can provoke controversy. Amis is by no means the first writer to go on the offensive on behalf of ‘serious literature’. American novelist Jonathan Franzen created a stir on being chosen for Oprah’s Book Club, declaring in an interview with National Public Radio’s Fresh Air that his 2001 title The Corrections was ‘hard for that audience’, and that the presenter had ‘picked enough schmaltzy, one-dimensional [books] that I cringe’. Franzen was accused by some of elitism and, according to fellow author Verlyn Klinkenborg, ‘an elemental distrust of readers, except for the ones he designates’. In the same interview, Franzen stated that ‘so much of reading is sustained in this country by the fact that women read while men are off golfing or watching football on TV’. He added that several male readers admitted to being put off by the novel being an Oprah pick, as if this automatically made for a female-oriented readership.

These comments are particularly interesting as regards the success of a writer closer to home. Irish author Colm Tóibín was longlisted for the Booker Prize in 2009 for his bestselling novel Brooklyn. While the book garnered acclaim, several female popular fiction novelists questioned the fairness of the reviews given the nature of the text. A brief summary of the novel—with its plot focused mostly on female characters and much given over to the protagonist’s love life and homesickness—is not very different to the kinds of stories written by Cecilia Ahern or Marian Keyes dressed up in Tóibín’s serious reputation. It is probably true that, if either had written the same text, they would not have been nominated for the most prestigious prize in English-language fiction.

So, is literary pedigree merely a matter of taste? Or can valid distinctions be made between works considered ‘serious’ or otherwise? Are the established classics just the product of the prejudices of a lot of dead and near-dead white men?

There is no straightforward answer; several variables, such as a writer’s style or the particular pretensions to which they might aspire, are usually good clues as to whom and how the novel is marketed.

It is now almost more a question of what not to read as opposed to what books we should devote ourselves to

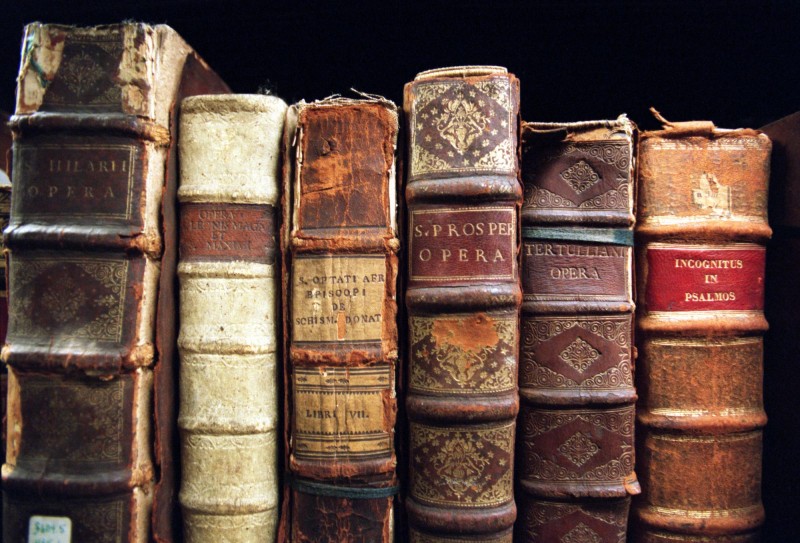

Perhaps the argument can be made that the canon proves its relevance by showing us which books to read. In 1602 the Bodleian Library of Oxford University had 2,500 volumes; a scholar who dedicated his life to their study could plausibly make his way through most, if not all of them. The same library now claims to hold 11 million printed items. After four hundred years, with countless titles since published and the distractions of the modern world to contend with, it is now almost more a question of what not to read as opposed to what books we should devote ourselves to. The canonical status of certain authors may serve as a guideline to worthwhile literature, but ideally this should not come at the mockery of supposedly less worthy writers, as reading is in itself a rewarding, enjoyable activity no matter the title or author.

In defence of this idea I refer you to two of George Orwell’s essays. In Good Bad Books he lauds ‘the kind of book that has no literary pretensions but which remains readable when more serious productions have perished’. Orwell invokes a similar idea to a more powerful effect in the later essay Lear, Tolstoy and The Fool. Referring to the Russian author’s extreme distaste for Shakespeare, Orwell declares that ‘there is no kind of evidence or argument by which one can show that Shakespeare, or any other writer, is “good”. Ultimately there is no test of literary merit except survival, which is itself merely an index to majority opinion’. If this is the case, we can be confident enough that Shakespeare, Tolstoy and countless other classic writers will continue to be read, as they have already stood the test of time. While my suspicions tell me that Katie Price’s novels will not be regarded in years to come as master examples of prose, this does not mean that her readers should be held up as fodder for the joyless would-be guardians of literary meritoriousness. Indeed, refusing to bow to what we’re told to like is, in the words of Robert Louis Stevenson, ‘to have kept your soul alive’—a principle that applies as much to reading as to anything else.