Edmund Heaphy | Deputy Editor

In January 2011, a few months before the Fine Gael and Labour coalition took office, the Higher Education Authority (HEA) released a report written by the strategy group assigned to develop a “National Strategy for Higher Education to 2030”. The report, referred to as the Hunt Report after its chairman, economist Colin Hunt, provides “a considered and informed basis for Government policy on the development of higher education in Ireland over the coming decades” or so the then-Minister for Education and Tánaiste, Mary Coughlan, wrote.

It would receive a D mark if submitted as an answer to a Commerce Degree exam.

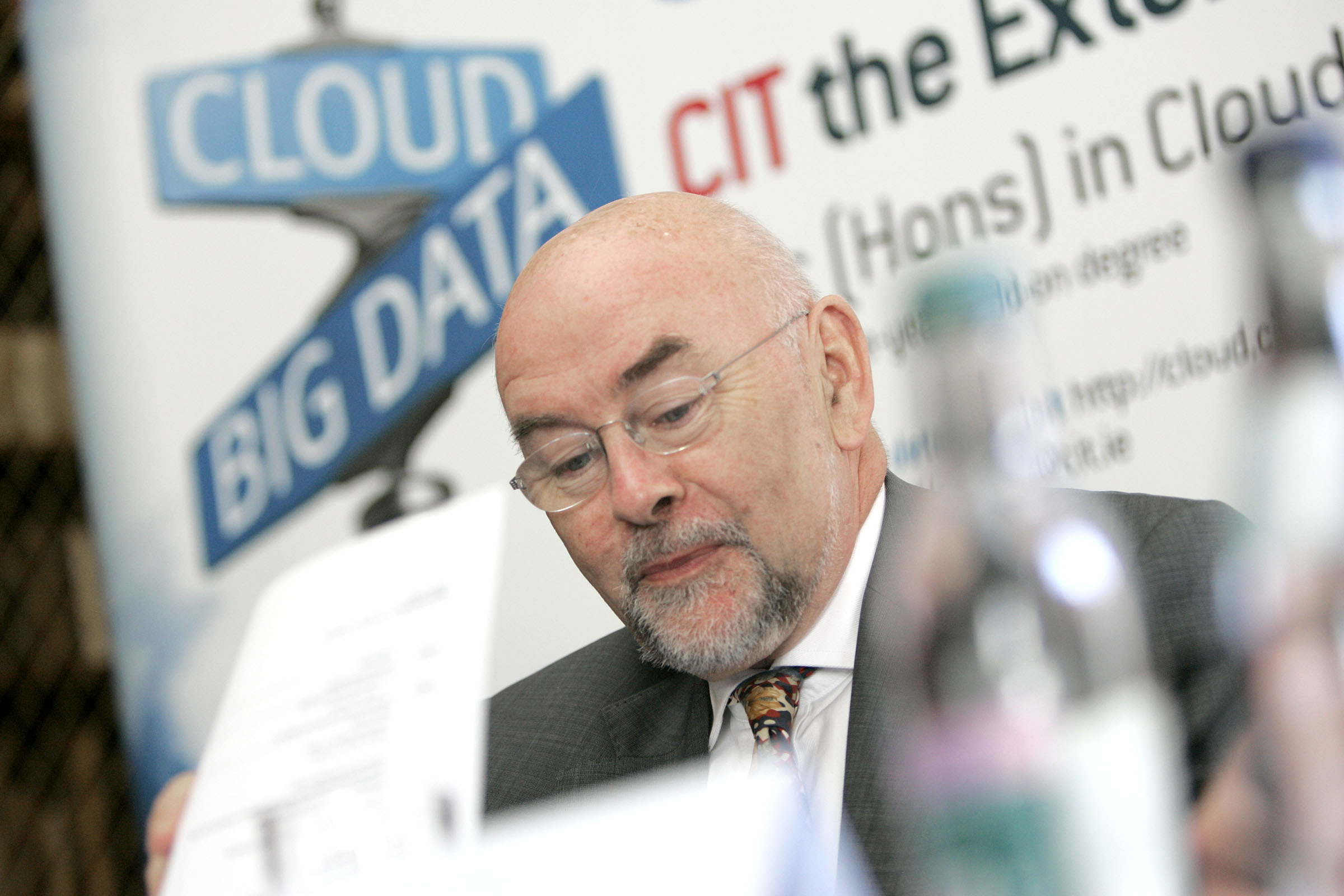

Ruairí Quinn, then an opposition TD and Labour spokesperson for Education, wasn’t exactly pleased with the report. Unimpressed by the six-month gap between the completion of the strategy group’s work and the publication of the report, Quinn accused it of being “particularly vague on the controversial issue of undergraduate fees” and said that it failed “to recognise that students already make a direct financial contribution for part time and postgraduate courses and that all undergraduates currently pay a €1500 charge, which will rise to €2000 next September”.

While Quinn welcomed some of the recommendations, such as the proposal to consolidate Institutes of Technology into mutually supportive clusters and the discussion on the high dropout rate among first-year students, he graded the report’s conclusions on the aspect of financing relating to fees as “vague, poorly described [and] not quantified in any manner”. He went as far as to say that it “would receive a D mark if submitted as an answer to a Commerce Degree exam”.

Quinn argued that, because the report only devoted two paragraphs to “implementation measures”, Coughlan should outline the steps that she would take, and that she should outline a “timetable for implementation” and form a task force “within her Department to whom she is assigning this responsibility”.

Just over eight weeks later, that very department became Quinn’s department. But that was after Quinn had, a few weeks before during the General Election campaign and in perhaps the most public way possible, committed to freezing the Student Contribution Charge at €1500. And he signed this great big pledge on College Green, right outside Front Gate with both USI and Trinity College Students’ Union present. Quinn explicitly told The University Times on that day that the €500 increase posed a “barrier at the entrance to education” that was “simply too much”.

Taking Office

A few days after taking office in March 2011, Quinn pledged to be a “new broom” in the Department of Education. Speaking at the annual conference of the Catholic Primary School Managers Association, his first major announcement was the Forum on Patronage and Pluralism, which laid the groundwork for one of his biggest achievements during his tenure: the questioning of the patronage of primary schools in Ireland. While significant progress has yet to be made on this issue – the Catholic Church is still the patron of more than 90 per cent of Irish primary schools – even the questioning of this issue is a major step. After all, his predecessors refused to even broach the topic. Quinn hopes that some issues to do with how religion is taught and dealt with in schools will be addressed by the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment this October.

The first signs of Quinn’s big U-turn came after he answered a written question in the Dáil

At higher level, Quinn quickly reversed the decision made by Batt O’Keeffe as Minister for Education in January 2010 to abolish the National University of Ireland (NUI), which counts UCD, UCC, NUI Maynooth and NUI Galway as constituent universities, among other colleges such as the Royal College of Surgeons and the National College of Art and Design. The abolition would supposedly have saved up to €3 million, but Quinn fairly logically concluded the savings would be negated by the additional costs that the constituent colleges would have accrued by performing the functions that NUI currently provides.

Quinn spent the rest of his first month as Education Minister battling the furore surrounding the revised Employment Control Framework, which had just been released – under the auspices of the previous government’s National Recovery Plan 2011-2014 from October 2010. The Framework, still in place today (and still making headlines), sets down strict limits for the number of appointments made in third-level institutions and sets pay grades for all staff in teaching, research, administrative or support positions working at third-level. More importantly, the framework gives the Higher Education Authority significant control over just who is appointed where, and gives them the right to turn down appointments even if they are funded through non-exchequer funds. Quinn had signalled that he would look at creative solutions to revising certain parts of the framework – which had been signed off by the then-Finance Minister Brian Lenihan just before he left office – and these materialised the following June when colleges were given more flexibility over promotions and were no longer were required to inform the HEA of appointments funded completely by non-exchequer funds.

Quinn closed that month off by shooting down Waterford Institute of Technology’s plans to become a fully fledged university, despite Labour having expressed support for the proposal previously.

Fees, Grants and the Junior Cert

In mid-April, Quinn announced that a single national authority would replace sixty-six third-level grant-awarding authorities for the following academic year. After an independent review, the City of Dublin VEC was designated the authority in charge, and they would later set up SUSI (Student Universal Support Ireland) as the subsidiary to handle the work previously completed by local authorities and local VECs. The system was widely commended, and for the first time, student grants were to be lodged automatically into the bank accounts of students.

That June, there were several news reports and indications from the Labour Party suggesting that full-blown tuition fees would be introduced

The first signs of Quinn’s big U-turn came after he answered a written question in the Dáil, submitted by Deputy Terence Flanagan. Asked whether he would make a statement on the matter of college fees, Quinn made no mention of this supposed €1500 freeze that he had committed to on College Green less than eight weeks previously: “With effect from the 2011/2012 academic year, a new student contribution charge of €2,000 will be introduced in higher education. This charge will replace the existing Student Services Charge and will apply to all students who currently benefit under the ‘free fees’ scheme. The contribution will be paid by the Exchequer in respect of students who qualify under the third level grant schemes.” That same day, Quinn announced plans for a major reform of the Junior Certificate. Since then, Quinn has put his full weight behind what can only be described as the discontinuation of the Junior Cert: from this September, incoming first-year secondary students will sit a new syllabus – starting with English – with 40 per cent of the marks coming from continuous assessment. This January, Quinn announced that it would be dubbed the “Junior Cycle Student Award”. Reports yesterday, however, suggested that the reform may hit serious roadblocks: it emerged that Quinn had failed to reach any compromise with teachers unions and talks which were supposed to take place in the last few weeks never happened.

In the context of his Junior Cert reforms, Quinn expressed desires to shake up the Leaving Certificate points race, saying: “we need to get away from rote learning”. He said that any change to the Leaving Certificate would have to come hand-in-hand with significant changes to the entry system at third level – and set a goal for it to be “axed” by 2014. The following September, Quinn had arranged for the the National Council for Curriculum and Assessment (NCCA) and the HEA to come together to discuss changes to the Leaving Cert. Almost three years later, while Quinn has made moderate progress, it doesn’t seem as significant as he had originally suggested. For instance, the reduction in the number of Leaving Cert grade bands announced in April is just a mere reversal of the 1992 decision to expand the system to prevent random selection – a problem which may reoccur. While the NCCA announced a major reform of Leaving Cert syllabuses in April this year, they amount to a significant reform merely in terms of the content of the subject courses rather than any changes to what makes the points race a points race.

On May 31, 2011, it became apparent that Quinn was indeed to renege on his College Green pledge, and that the Student Contribution Charge would rise to €2000 the following year. In terms of dramatic and altogether blatant U-turns, Quinn’s failure to stick to what seemed like a completely concrete pre-election promise – just three months after he put a Sharpie to cardboard outside Front Arch – ranks pretty highly. And it wasn’t just that €500 rise that Quinn was backtracking on. The same pledge binded him to campaign against “any further increase in the Student Contribution Charge”. Yet, the following year, it was increased by yet another €500 to €2,500, and in the last budget, it was announced that the charge for the coming year would amount to €2,750, and that for the academic year beginning in 2015, the charge would amount to €3,000, 100 per cent more than it was the year before Quinn took office.

Instead, he cancelled the plan to act on the recommendations of the report and announced that yet another working group was to look at the issue

That June, there were several news reports and indications from the Labour Party suggesting that full-blown tuition fees would be introduced, when Quinn said that, despite the fact that “Putting a financial barrier in front of people on the way into college” had “shown to be a deterrent”, the country was in the midst of a “serious financial crisis nationwide and also in the university sector, and [they had] to address that”. Joan Burton didn’t seem to have any bones to pick with his comments, saying that he was “reflecting reality”. Quinn commissioned the HEA to conduct a report on the funding situation, to be delivered by the end of the year.

The following month, Quinn firmly ruled out the possibility of a student loan scheme in lieu of either directly paid tuition fees or the Student Contribution Charge. This type of loan scheme was mooted only last week by Professor Andrew Deeks, the newly appointed President of UCD, when he said: “My personal view is that the contribution system that has worked in Australia for the past 20 years now provides a good model. It is a deferred payment of a debt, which is accumulated module by module as students progress through the course.”

Yet, back then, in August 2011, Quinn was as definitive as one could be about such a scheme: “The student loan system would, in my view, become an emigrant incentive. And instead of the illegals saying to Mammy, ‘I can’t come home for that funeral because then I won’t get back into the United States’, it will be ‘I can’t come home because then I’ll have to pay my loan’.”

The following November, the HEA published the report Quinn had commissioned earlier in the year on the funding situation entitled “Sustainability Study: Aligning Participation, Quality and Funding in Irish Higher Education”. The key recommendation of the report was that an increase in the level of the Student Contribution Charge should be considered in the short term “if and when further declines in public funding for higher education become necessary”. In the longer term, the report suggested just what Quinn was vehemently opposed to: “the establishment of a student loan facility” which it said would represent “a long-term investment in addressing the structural skills deficit in the Irish workforce associated with levels of educational attainment of adults in the workforce that are low by international standards” by reducing the possibility of new barriers that would “compromise equitable access”.

Understandably, given his prior opposition to the very recommendations of the report, Quinn downplayed its results, and it received little media attention because of it. Instead, he cancelled the plan to act on the recommendations of the report and announced that yet another working group was to look at the issue and report by the end of 2015.

More on University Entry Reform

September of Quinn’s first year as Minister for Education saw the release of the “Entry to Higher Education in Ireland in the 21st Century” report, written by Professor Áine Hyland of UCC. Hyland served as Chairperson of the Commission on the Points System, a group set up in 1997 by the then-Minister for Education, Micheál Martin, “to examine the system of selection for third-level entry in this country”. Over the two years that the commission sat, they met thirty-two times and held several public consultations across the country before publishing their final report in 1999.

The two-subject moderatorship course, Trinity’s largest course, is the culprit.

The report, which rather than making sweeping recommendations, was more descriptive in nature, found that the points system in Ireland was fairer and more transparent than systems in most other countries. Hyland’s newer report in 2011, now referred to as the Hyland Report, presented several options for reform of the CAO system, most notably a system which would take into consideration the strengths of Leaving Cert subjects related to the course they were applying for, rather than simply minimum entry requirements and an overall, more general points total. Quinn said: “The charge has been that the Leaving Certificate places performance pressures on students that promotes ‘rote learning’ and a narrow emphasis on the terminal examinations themselves at the expense of broader learning opportunities through the senior cycle.”

Quinn was prolific when it comes to commissioning reports. Last year, he published the “Supporting a better Transition from Second Level to Higher Education” report, which contained discussions of several issues he would later ask the Oxford University Centre for Educational Assessment to investigate, specifically in relation to investigating the perception that the contents of Leaving Cert exams had become predictable, and a second report into the aforementioned narrowing of grade bands in the Leaving Cert. The report also contained preliminary recommendations proposing broader entry courses at university level to combat the stark rise in the number of courses available through the CAO system.

In April, Quinn announced the reduction, which brought the number of Leaving Cert grade bands down from fifteen to eight, which he hoped would discourage students from trying to score every mark in Leaving Cert exams.

The final leg of this “Transition” report seeked to increase the number of general-entry courses for incoming first-year university students – something initially suggested in the Hyland Report. This would theoretically reduce the points required by expanding the number of places in a course and allow for specialisation later. The number of courses available through the CAO system has steadily increased. In 2011, there were 850 level-8 courses. Incoming university students had more than 950 to choose from this year – a rise of more than a hundred in the space of just a few years. Trinity in particular is to blame: we have more than 237 course codes to choose from, which represents more than 40 per cent of all level-8 course codes on the CAO system.

A few days later, Quinn denied that he had lied to students when he signed the pre-election pledge

And Quinn’s department, in conjunction with the CAO and the Irish Universities Association (IUA), has come down hard on Trinity for this. The two-subject moderatorship course (TSM), Trinity’s largest course, is the culprit. It’s 25 subject choices mean that there are 176 separate CAO course codes. In December, the Senior Lecturer, Professor Patrick Geoghegan, sent a memo to the TSM Course Director, Professor Moray McGowan, after a meeting with representatives of the IUA and CAO where he provided “reassurance that Trinity was looking seriously at the issue of reducing course codes, and in particular was working on TSM, and that while we may not have any definite solutions we have not ducked the issue”. Geoghegan noted the possibility of offering “the exact same combinations” but reducing the number of CAO codes to 25, saying that it would change “nothing in the way anything works”, although he was unsure if it “would be acceptable to the [IUA] Task Group”.

Postgraduates, the Axe and Scholarships

In November 2011, it became apparent that the government was seriously considering cutting off grants – worth up to €6,000 each – going to up to 3,600 postgraduate students. More than a third of postgraduate students had been eligible for free fees and state grants. This was, for USI and for most students, the final nail in the coffin that contained that pledge Quinn had made outside Trinity before the election. In advance of the budget in 2011, Quinn refused to make any promises, saying: “The politics of promises, if you like, in the present economic situation are such and are on a scale that I don’t think any of us fully realise that no such promises can be given and any such promises would be misleading.”

A few days later, Quinn denied that he had lied to students when he signed the pre-election pledge: “No, I didn’t lie, and I haven’t lied, but I am, along with 14 other Cabinet colleagues, dealing with an incredibly difficult budgetary situation, which the interests of students, which I support, I want to see participating in third level and not being unable to participate purely for money.”

As part of the budget that year, the maintenance grant was indeed abolished, with the only consolation being that funding relief would be offered to students whose family income was less than €20,000 per annum.

The following April, Quinn announced the phased introduction of a new scholarship scheme for third-level students from disadvantaged backgrounds. This formed part of his commitment in the previous budget to abolish the disparate scholarship schemes and combine them into one. That year, sixty medical card-holding students from DEIS schools were awarded a bursary of €2,000 on the basis of their Leaving Cert results. The number of scholarships has risen since, and it’s expected that up to 350 students will benefit from the scheme next year.

He muttered a few sentences about technological universities, and moved on to how the quality of primary and secondary school buildings always amazed him.

That July, Quinn noted in a response to a written question that a number of financial institutions already offered loans for postgraduate students, but that he was liaising with institutions “in relation to the potential development of further competitive loan packages” to provide support to those who previously would have been eligible for the maintenance grant. A few weeks later, Quinn formally endorsed such a loan scheme from Bank of Ireland, which would offer up to €2,000 to students to pay for their studies. Repayments under the scheme are interest-only until three months after graduation. USI President, John Logue, was very critical of the scheme, saying that it was “patently a scheme that will only help students who are already in a comfortable financial state”. It was reported at the time that discussions between the Department of Education and some financial institutions involved proposals of a similar undergraduate scheme, with Trinity to be a testing ground, although that never materialised.

Speaking Little of Higher Education

The following summer, in August 2013, Quinn addressed the Magill Summer School in Donegal. His speech was notable, not for its focus on Ireland in twenty years time – he wanted to consider how Ireland will interact with the wider world in the 2030s – but instead for how little he spoke about higher education. He tried to address the issue by coming out and saying “I’ve spoken little of the future of further and higher education in Ireland”. Indeed, he had. He muttered a few sentences about technological universities, and moved on to how the quality of primary and secondary school buildings always amazed him.

It’s perhaps the most categorically stupid pledge ever made during an election campaign rather than something done maliciously

In January this year, Quinn brought proposals for the creation of technological universities to cabinet, and published the heads of the bill in April. This is perhaps one of the most significant achievements that Quinn has made in higher education – but that says more about how little he had done for the “traditional” university and third-level institution than what he is achieving with the introduction of technological universities. Perhaps it is befitting, however, given the idea of technological universities was one of the few things he commended in the Hunt Report – the very report he had given a D-grade just weeks before he took office in 2011.

Three clusters of institutes of technology are preparing plans to merge into three separate technological universities. Quinn said that the bill “represents an essential milestone in the modernisation and reform agenda for higher education institutions.”

Regarding Quinn’s track record with higher education, I spoke briefly to Mike Jennings, the General Secretary of IFUT, the Irish Federation of University Teachers, who said that they had “a good relationship with the Minister and found him approachable and accessible”, though he expressed regret that Quinn “was in office at a time of such financial difficulty as we felt he had a greater ‘feel’ for higher education than most of his colleagues”. While he may not have made significant progress or reformed the higher education sector during his term, Ruairí Quinn was Minister for just over three years, which in the grand scheme of things, isn’t a lot of time to get things done. His reform of the Junior Cert and the adjustments to the way things are done at Leaving Cert level, along with his challenging of the Catholic Church’s patronage of schools are sweeping changes which we won’t know the results of for some time – but he did get stuff done.

His pledge in front of Front Arch not to increase the Student Contribution Charge seems like it was made in good faith, which really makes it seem like perhaps the most categorically stupid pledge ever made during an election campaign rather than something done maliciously.

In their statement after his resignation, USI noted that “Quinn was one of the very few ministers prepared to come to USI congress to defend his position, take questions and debate the reasons why” and that he “engaged with USI on a regular basis and initiated a constructive and frank relationship with the student movement”.

And that is the general feeling: if the situation was radically different, Quinn could have been just the person to transform the entire education landscape.

The members of the working group – the one looking at third-level funding that Quinn announced in 2011 – were announced last week, making it one of his last acts as Education Minister. It’s notable that he named Joe O’Connor, the outgoing President of USI, to the board – a gesture that shouldn’t go unnoticed.