Aisling Curtis | Senior Staff Writer

Buying a house is one of those milestones that seems frighteningly mature and intangible, a looming landmark on the road towards old age. For many of us, renting our own place – and the myriad shopping, electricity, and upkeep concerns that go hand in hand – is enough responsibility. For others, even doing their own washing without a mother’s help is a pretty big step.

But nowadays buying a house may remain unattainable for a much longer stretch of time. Under new mortgage rules set to kick in on January 1st, prospective buyers will need to raise 20 per cent of the property value in order to qualify for a loan, instead of the original 10 per cent. For young people, who will enter the workforce on lower-paying jobs and would have spent many years building up the financial resources to afford even 10 per cent, this decision has placed homeowning more squarely out of reach. We will be renting – or living at home – for years down the line.

Sometimes I stare at the hazy horizon that embodies ‘The Future’ and wonder if I’ll ever have a proper job or my own home.

This line that has become longer and longer, until sometimes I stare at the hazy horizon that embodies ‘The Future’ and wonder if I’ll ever have a proper job or my own home. When our fledgling careers seem composed of poorly-paid internships and further education and fleshing out our CVs, you wonder how that could ever transform into a solid, reliable wage. For us – Generation Y, the Millenials, the children dropped like stones into the midst of an economic catastrophe that we had no part in until we were forced to pay the price – our ability to reach adulthood has been brutally constrained. The traditional ingredients of maturity, defined by sociologists as completing school, leaving home, becoming financially-independent, marrying, and having a child, are no longer readily available, at least within the timeframe once expected of young people.

Conventionally, generations followed a neat and orderly advancement, building blocks of career-marriage-kids, with retirement being the culmination of such organised growth. A cyclical pattern, wherein the older raised the younger, and were supported by them when their own turn came.

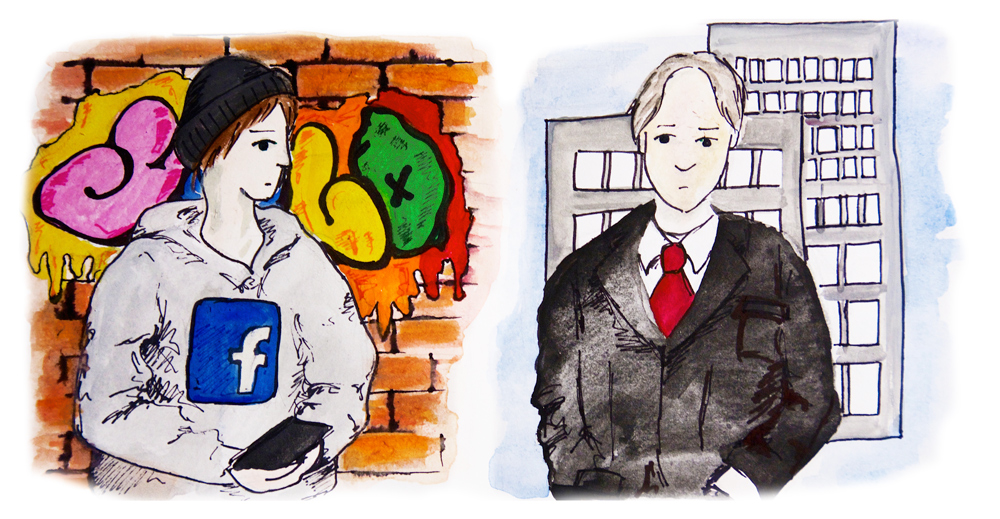

But now? Now, the progression for 20-somethings resembles a splatter of data points rather than a coherent line. 42 per cent of Irish young people are still living with their parents, we experience an average of seven job changes in our twenties and the average age of marriage in Ireland is 33.1. The traditional narrative has been gracelessly scattered, pushed further into the future, and shunted to the side, as a consequence of a cultural shift or an economic implosion, or more likely both. Regardless of the cause, the 20-somethings of today are the teenagers of twenty years ago; the thirty-somethings that we will become will only be getting around to the activities our parents had ticked off at that age.

No other generation has been impeded so radically, and we likely won’t know the consequences until it’s too late to resolve them. It’s an unintentional social experiment that could very easily go wrong.

Delaying adulthood does not just give us a few more years to shirk responsibility and not pay rent, it excludes us from society, from employment opportunities, from the chance to do the grown-up stuff that seems tedious now but will be highly relevant when we want to retire and find that we can’t afford it yet. No other generation has been impeded so radically, and we likely won’t know the consequences until it’s too late to resolve them. It’s an unintentional social experiment that could very easily go wrong. Will 75-year-olds still be forced to work, incapable of paying off mortgages or building up pensions because they didn’t find a well-paid job until they were in their 30s at best?

Unless somebody does something about this aggressive social exclusion – the lack of employment, the lack of housing, the lack of just about everything that we once trusted as markers of maturity – this generation is going to be the litmus test. This generation can also be the first line of defense.

Illustration by Caoimhe Durkan for The University Times