Seán Healy | Senior Staff Writer

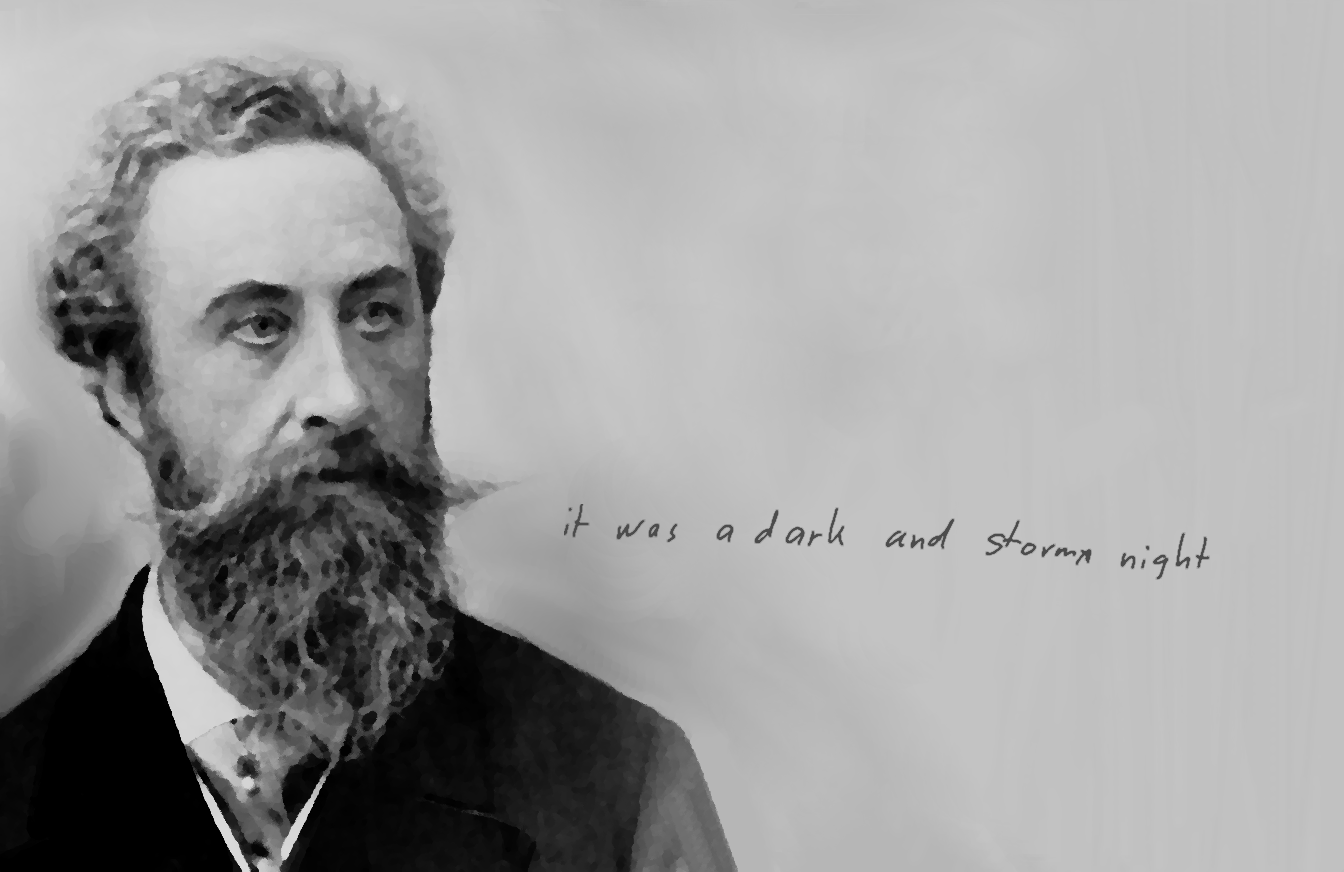

The Inklings, a literary discussion group from Oxford, once held tournaments to decide who could spend the longest time reading the work of Amanda McKittrick Ros without laughing. J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis were members of this club that took ironic joy from reading what has been described as the worst writing ever produced. McKittrick Ros’s legacy, along with that of William McGonagall – described as the worst British poet ever – lives on in biographical Wikipedia articles. For over 30 years, the Bulwer-Lytton Fiction Contest has taken entries of the worst opening sentences in fiction, for the prize of a “pittance”. I remembered these stories while watching Liam Neeson in “Run All Night” last week.

Liam Neeson took on his typical role, mirroring his protective protagonist in Taken 3. Some of the scenes were so unoriginal, I was set on a tangent recalling which movies they had been stolen from. The chase in the subway station: Skyfall and many other spy flicks. The feet-scraping strangulation on the bathroom floor: No Country for Old Men. The “oh right, he’s a bad guy” scene, with an overly bloody murder following a calm conversation: Gustavo Fring, Breaking Bad. When the “catholicism, drug trade, racial group” plot trio were brought in, I resisted spitting 7up out of my nostrils, as I began to notice the film was attempting to emulate The Godfather.

J.R.R. Tolkien and C.S. Lewis were members of this club that took ironic joy from reading what has been described as the worst writing ever produced.

It might seem obvious that most people wouldn’t decide to watch a film of poor quality. But there is art made of such unintentional poor quality that it becomes unintentionally hilarious to appreciate. As with the Bulwer-Lytton or the Inklings’ ironic contests, there’s an entire culture and community surrounding terrible movies, where the audience are aware of the movie’s flaws.

In The Disaster Artist, Greg Sestero, who played Mark in the cult movie, The Room, outlines the amount of money that went into the production of the film. The Room, directed by Tommy Wiseau, produced by Wiseau, written by Wiseau and featuring Wiseau as the main character, cost millions to make, and made barely anything when it came out in cinemas. Just like its predecessors – for example, Manos: The Hands of Fate – its initial failure on the market was turned into absurd success as word of its awfulness spread. Today there are screenings of The Room worldwide. Dublin University Alternative Music Society screen the film around freshers week with ceremonial throwing of spoons or American footballs and chanting of quotes – all customs of a small cult audience perplexing the outside world.

Performing these activities while watching the film suggest that the experience of appreciating bad art differs greatly from the norm. Being a fan of The Room, I’d usually only watch the film with a group of friends while drunk. I recently set up a survey to take a closer look at adjacent aspects of cult film culture. Distributing the survey to conversation groups across the internet, and with 129 replies, 39 per cent reported watching the movies only while sober. Meanwhile, 51 per cent replied that they pair their viewing of “bad movies” with alcohol, and 26 per cent replied that they enjoy the movies with the addition of marijuana.

Dublin University Alternative Music Society screen the film around freshers week with ceremonial throwing of spoons or American footballs and chanting of quotes – all customs of a small cult audience perplexing the outside world.

The hedonism that goes with it, to the point where the experience is not only habitually given customs and good company, but where some get drunk and high to make the most of it, doesn’t do much for cult bad movies’ perceptions among professional critics. Only 9 per cent of those answering the survey stated they watch classic bad movies for reasons including character study. Critics on IMDb and Rotten Tomatoes are presumably sober while working and reviewing, and the very low ratings from these media groups for the likes of Troll 2 reflect traditional critique.

Knowing people who enjoy the film, sober or not, I included a question to dispute the current system in artistic critique. The restrictive scale of one to five stars, thumbs up or thumbs down, doesn’t always indicate how enjoyable or insightful something will be. When I posed the idea, “bad movies” are good movies, 54 per cent agreed with this comment. But a noticeably high 21 per cent neither agreed nor disagreed, but responded otherwise, stating that a black and white interpretation of critique is unsuitable. To exemplify this view, I personally find it difficult to sit through the entirety of Nosferatu (1922), which has a 97 per cent rating on Rotten Tomatoes. Yet I easily remained sitting until the end of Run All Night, because I was having so much fun watching the producers slaughter an entire genre.

Many comments left on the survey predicted this point, and in turn stated that the enjoyment stems from the fact that the film was not made to be bad – that the failure was real. It seems, therefore, that our enjoyment is not a valid review for whether the art is good or bad. I do take enjoyment from bad movies due to their unpredicted failure. But the enjoyment is more than schadenfreude or even a confidence boost. After watching some creatively lacking “bad movies”, especially if independently made, it’s often possible to receive insight into the creators rather than the characters.

I became fascinated with Wiseau after watching The Room. His character, named “Johnny”, would stumble into scenes where he had no place. He would say things so abnormal by most standards. Wiseau attempted to make a film about a loving man in a relationship with what is described in the film as a psychopathic woman, but the way he executed his story instead revealed a lot about his own personal flaws, controlling nature and eccentricity. I wasn’t overly surprised to later read that many left the set and that he dictated everything from costume design to bizarrely purchasing equipment rather than renting cameras.

Wiseau attempted to make a film about a loving man in a relationship with what is described in the film as a psychopathic woman, but the way he executed his story instead revealed a lot about his own personal flaws, controlling nature and eccentricity.

I regretted the schadenfreude when I later read Sestero’s biographical recount. Wiseau is portrayed as a disconnected character, leading a scattered life, driving slowly on the highway for fear of crashing, always exaggerating his youth and writing plots that bring him into the feeling of friendship – Sestero’s friendship, for example. These personal traits had repercussions for his coworkers, as his delusional goals drove many of them to suffering, humiliation, and even relationship problems with others. But as much as I still laugh with enjoyment while watching Neeson shamelessly pick up a paycheck in a knowingly awful film, this revelation, that my hipster euphoria was based on drunkenly replaying someone else’s dreams and failures, changed my view somewhat.

In the survey, only 9 per cent described their reasons for watching bad movies as relating to something “hipster”, yet 44 per cent listed this characteristic when asked why others watch these films. Although I will still watch The Room for love of Wiseau and perhaps submit a line to some ironic contests like Bulwer-Lytton, my schadenfreude paradise has popped. Next comes the challenge of searching for gratification outside of watching others fail.

Illustration by Seán Healy for The University Times