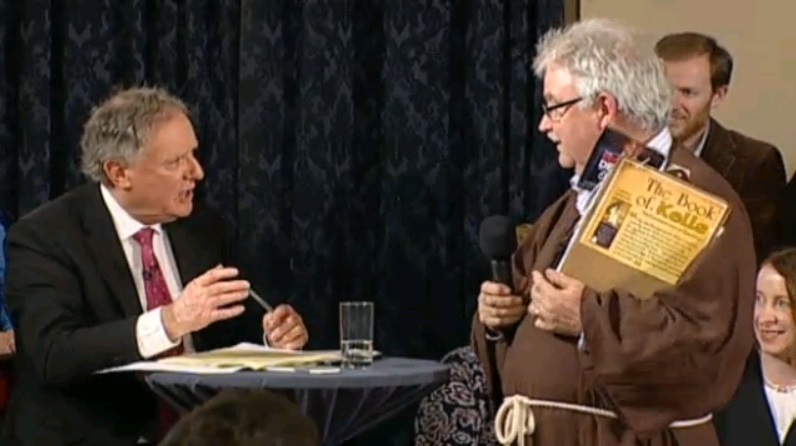

During mid-June, students visiting College through the Nassau Street entrance to the campus may have overheard a rant by a man brandishing a sign and microphone. Earlier this week, he was standing outside Front Gate. Ronnie McGrane, a campaigner and editor of Kells Online, speaks of the rightful ownership of the Book of Kells and boldly breathes new life into the controversy that has persevered in the years since the book’s move to Trinity in the mid-17th century.

The Book of Kells has been housed by Trinity since the 1660s, its fame and glory now attracting approximately 700,000 visitors each year. The priceless example of rich Irish heritage finds itself near the top of the “to visit in Ireland” list, alongside the Boyne Valley, the Cliffs of Moher, the Giant’s Causeway and the Guinness Storehouse. Yet not all are satisfied with the limelight the book enjoys in the heart of Trinity, particularly the town from which the book borrows its name – Kells, in Co Meath.

The small town is an area deeply rooted in the annals of Irish history and heritage. The Abbey of Kells had been the home of the book for the better part of eight centuries before its move to Trinity. While the origin of the book is disputed, many believe that work on the manuscript began in the monastery of Iona, off the coast of Scotland. It is believed that it had been smuggled to Kells for safekeeping by the Abbot and the Columban monastic order.

Not all are satisfied with the limelight the book enjoys in the heart of Trinity, particularly the town from which the book borrows its name.

Throughout the seventh and eighth centuries, Iona suffered Viking raids due to its open location, and the Abbey of Kells had become the new home for the fleeing monks and their treasures. Having founded the Abbeys both in Iona and Kells in the middle of the sixth century, St Columba – more commonly known as St Columcille – had established a legendary tradition in copyright law. This latter point is strenuously noted by writer Ronan Sheehan, who works with Ronnie McGrane on the Kells campaign team. Sheehan uses this tradition as his argument for the return of the Book to Kells.

Sheehan has published a number of articles touching on Columcille’s tradition. He writes of a time when Columcille had visited St Finnian’s monastery at Dromyn and copied a psalter without Finnian’s knowledge, who on discovery claimed the copy as his own. The High King of Ireland defended the move in his famous sentence: “to every cow its calf, to every book its copy”.

Columcille disagreed and was exiled to Iona, where he founded his monastery. He sought to spread the wealth and the word of the psalter amongst the lay people. This take on Columcille’s law is revived by the Kells campaigner, and Sheehan declares that if Columcille himself was resurrected, he would not be impressed to find that Trinity “claims a copyright interest in the Latin gospels made in the monastery he founded”.

Sheehan’s partner, McGrane is a Kells businessman in addition to being editor of kellsonline.ie. An active and notable spokesman for the Book of Kells Campaign, McGrane seeks to return the Book of Kells to his hometown in Co Meath, and amusingly declares himself a “threat to the millions that [Trinity] have collected from our book.”

This is not the first attempt by Kells to claim the book back. McGrane vents his agitation at how both the government and “the town people have been ignored for centuries. We launched this campaign from a different prospect as the government direction wasn’t working.” He compares his media-based attack on Trinity’s ownership of the book to Cromwell’s campaign against the Irish, saying “the bigger they are the harder they fall.” However, aside from having a subsection on the Kells site, a few appearances on Irish broadcast television and community meetings, this visual attack amounts to little more than McGrane haunting the college in monk’s attire.

McGrane seeks to return the Book of Kells to his hometown in Co Meath, and amusingly declares himself a “threat to the millions that [Trinity] have collected from our book.”

Having proven difficult to correspond with, McGrane speaks to The University Times via email of how, on Cromwell’s rise to power in the mid-17th century, one of his generals – Henry Jones – was appointed Bishop of Meath. It is after his appointment to Vice-Chancellor of Trinity that the book was moved from the Abbey in the mid-1650s, and soon found itself in Trinity. The law meant permission was required from the owners to move the book, but neither Columcille nor his monastic order were in Kells, leaving the ownership of the book in a shady area.

While not claiming ownership of the book, Trinity does own the copyrights to the manuscript and charges a fee at the entrance to its exhibition. The fee applies to both tourists and the people of Kells alike, which McGrane states is one of Kells’ issues with the book being displayed in College. Head Librarian of TCD, Helen Shenton, insists that Trinity’s copyright of the book is of mutual gain. Having declined an interview with The University Times, she says in a prepared email statement that the “proceeds from Old Library income are re-invested in the care, curation and display of the manuscript along with the overall conservation and maintenance of the Old Library and its collections.” If McGrane had further doubts regarding how beneficial the book’s place in Trinity is, Shenton elaborates on its wider advantages, adding that “a significant financial contribution is also made to college every year for wider research and educational programmes.”

These include the digital collection of the manuscript online, the launched iPad app, the high quality banners and leaflets with tourist information in multiple languages, as well as endless preservation work and security regulations that are maintained and funded by Trinity. This could be read as a shameless plug of the Trinity brand, but nonetheless it projects an image of cultural pride. Although McGrane questions Trinity’s ownership of the book’s copyright, it cannot be said that college squanders it. Still, the unimpressed McGrane, whose argument repeatedly deviates from the ethics of ownership of the book, states that “the Book of Kells is the most famous manuscript in the world, it does not need to be advertised.”

He claims, ‘There is more condition, temperature, humidity and dust control in your Mercedes car than there is around the book.’

The aim of the campaign is to bring the book “back as a mark of respect to the monastery of saints and scholars burned by Cromwell.” When pressed about the logistics of this, McGrane only lamented that “the return of the Book of Kells is impossible now as a single gospel because Trinity tore it up in four pieces.” What McGrane refers to is how the book was divided into four gospels after being rebound in 1953. It is displayed in the Old Library in two volumes at any one time.

Shenton assures us that “stringent security, conservation and environmental controls are in place to ensure the safety and good condition of the Book of Kells.” Yet McGrane, who, when asked, admits that he has not visited the book since his primary school days, is not satisfied with the conditions of the book. He claims that “There is more condition, temperature, humidity and dust control in your Mercedes car than there is around the book.” His proposition is to hold the book in a “purpose-built monastery of the period, and show and act out the period – an experience” which an average tourist could link with the Kells Road Races and the Hay-on-Wye Festival.

When pressed on it, McGrane refrains from disclosing the details of the business plan for this largely commercial project. He further claims that the funding will come from Australia and the US, but again does not share how this will be achieved. With this financial objective in mind, he adds: “We also emailed the Pope and the Queen.” His aim is that “the monastery with the town would become a World Heritage Site with tourists from worldwide, like the Taj Mahal, where I got my inspiration.”

By campaigning outside the college, McGrane hopes to open dialogue with Trinity regarding the question of the book. “I think we need to talk first about the damage to our book and put it back together as it was.” Despite his passion on the subject, there is little evidence of McGrane actively contacting College for discussion on the topic.

With this financial objective in mind he adds, ‘We also emailed the Pope and the Queen.’

Seeking to assist McGrane, The University Times contacted the Head of Preservation, Susie Bioletti, and the Keeper of Manuscripts, Dr Bernard Meehan requesting interviews in an attempt to aid this dialogue. However, only Shenton provided comment in her email statement. She nonetheless recognises “the attachment members of the Kells community have in relation to the Book of Kells” and states that “Trinity College Library is involved in local events in Kells around the Book of Kells.”

Today we know the manuscript as the Book of Kells, and yet throughout its existence it bore many other names such as the Book of Columcille, or the Great Gospel of St Columba. While the name changes and the manuscript ages, so too do the controversies along with it. The question of “Who owns the Book of Kells?” is a difficult one to answer, and certainly there are better ways to answer it than protesting in a monk’s outfit on Nassau Street. Regardless, each attempt to move the book adds a page to its history – a story which already displays the wealth and heritage of Ireland not only on a local, but also on an international level.

Correction: 23:10, Sep 12, 2015

Due to an editing error, an earlier version of this piece incorrectly asserted that McGrane refused a phone interview.