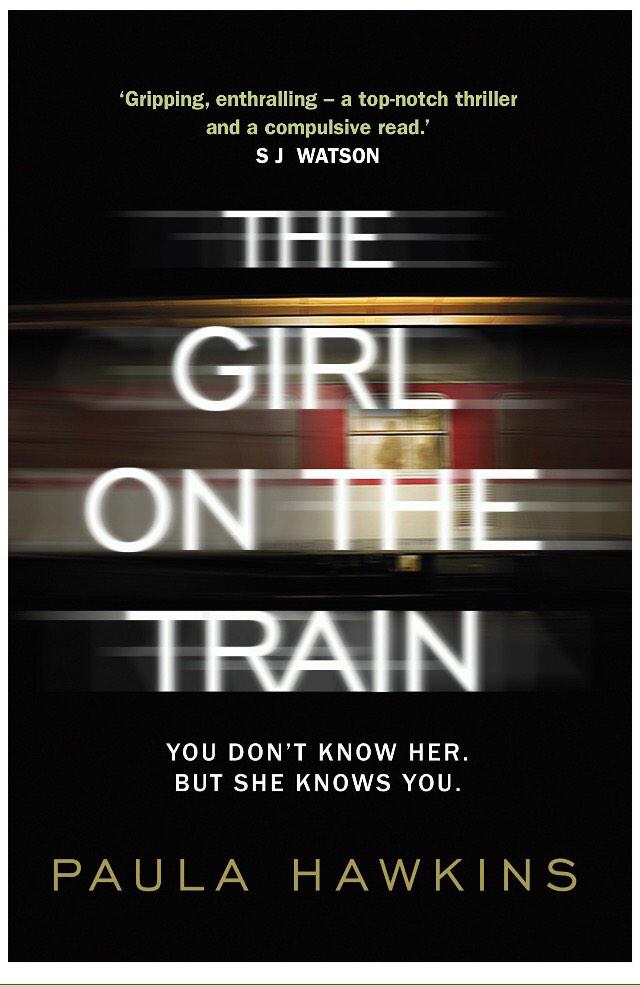

It is wrong to assume that Paula Hawkins’ debut thriller “The Girl On The Train” is just another “Gone Girl”. Indeed, the novel, which continues to hold its place in bestseller lists worldwide since its publication, plays host to a gripping and sensational narrative that demands the reader’s full attention from the off, yet in very different ways to its literary competitor.

Hawkins taps into the sense of unease that every commuter experiences at one point or another in their journey — the uncertainty of who exactly could be sharing their commute with them. Upon meeting Hawkins’ protagonist, Rachel Watson, the reader too can find themselves experiencing exactly the same sentiment. Who really is this girl?

The narrative provided by Rachel is chaotic. As she travels on the 8.04 train to London each morning, her fantasies about the people that she passes on a daily basis mask a deep sense of bewilderment that Hawkins invites the reader to tap into. This is clouded further by Rachel’s acute alcoholism. As her fantasies grow, however, the distinction between imagination and disillusionment become quickly blurred, namely in relation to her obsession with a couple living beside the train tracks. From afar, Rachel envisions a picturesque life for Jason and Jess, despite having never met them. The distance between Rachel and the couple allow her fantasies to grow, but as they do, the reader is pushed into the realisation that what Rachel projects onto the couple is not something that she craves for herself, rather something that she has tragically lost. Indeed, Rachel once lived on the same street as Jason and Jess, with her husband, Tom.

The novel’s pace quickens when Rachel notices suspicious behaviour surrounding her beloved couple. Jess, who is outside of Rachel’s fantasy is called Megan, goes missing in the immediate aftermath. Feeling a responsibility towards Megan, and distrust of Jason, who in reality is named Scott, Rachel cannot help but get involved.

At this point, the narrative is shared between Rachel, Megan, and Tom’s new wife, Anna. The three women are not only connected by the railway that winds around the back of their houses, but by the gut wrenching events that permeate their lives. Through the events that unfold, Hawkins relentlessly forces the reader to decide for themselves whether what they are reading is the truth, or a dream created in a hazy blur of alcohol fuelled uncertainty. Hawkins cleverly employs this tactic to ensure that “The Girl On The Train” cannot be abandoned by the reader until the very last page has been turned.