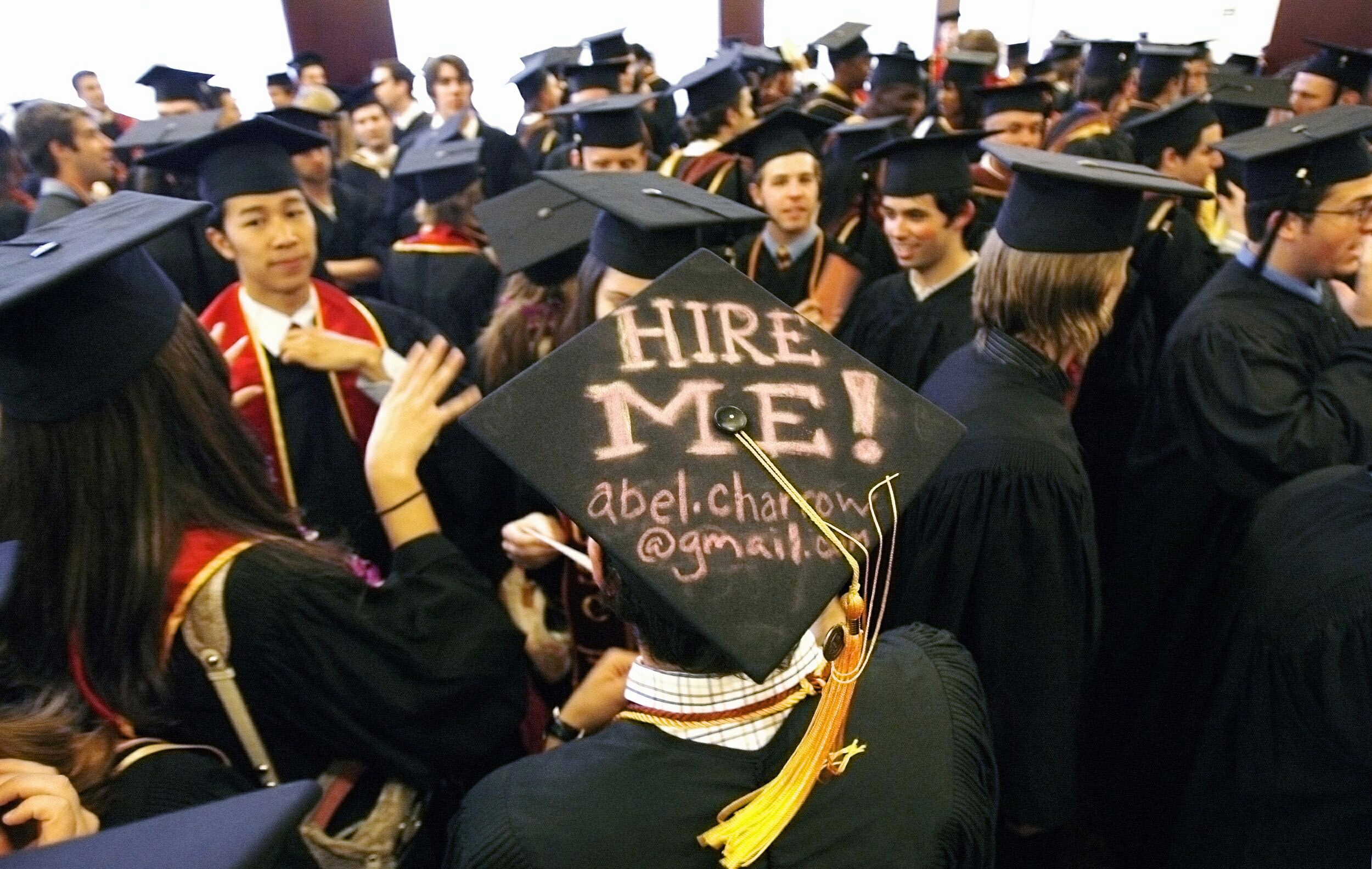

If we think of our education system as a funnel, with an unseen force driving students through second and third level education, then the corporations who hire our graduates are holding a bucket at the bottom and laughing as they walk away.

Grad recruitment is many things: it’s exciting and optimistic, stressful and overwhelming. It’s also predatory, opportunistic, and emblematic of some of the worst traits of capitalism. As I wandered around the hall of RDS Simmonscourt last week in the teeming mass of sweaty nervous bodies that’s more commonly known as the GradIreland Careers Fair, it was difficult not to feel depressed. Every five minutes, hundreds of identical interactions, selling false hope, promising the world. Each piece of paper, company pen, and, if you were lucky, crumpled bag of Haribo enticed you further in.

I sit at my desk, surrounded by potential future lives.

I drifted in and out of a thousand conversations, interrupting someone’s hopes and dreams to grab a programme at a busy stand. A half-muttered apology, and on to the next one. Quickly despairing of the voices of recruiters, I put my headphones on, tuning out the chaos. A few days later I sit at my desk, surrounded by potential future lives. I consider one, re-read and dismiss it, crumple it in my hand and throw it into the bin at my feet, which has become alarmingly full.

I begin reflecting on the underfunded education system that I’m going to leave next year, and the over-eager companies waiting for myself and others to finish. For a country to educate someone from junior infants until they finish their undergraduate degree is expensive. Ideally, the government would be putting more money into education, in all sectors, and there have already been countless think-pieces on where that money should come from. me, it seems obvious that the companies that benefit so much from our graduates, and the skills and knowledge that they bring with them, should be contributing in some way to the funding of that education system. If these companies are going to participate in an annual harvesting of our brightest and best with such efficiency and glee, then it seems only fair that the country which has funded their education sources some of its funding for that same education from them. The working group on the funding of higher education is due to report back before the end of the year and one particular suggestion made to them addresses this idea.

For a country to educate someone from junior infants until they finish their undergraduate degree is expensive.

In September 2014, the Irish Federation of University Teachers (IFUT) submitted a policy paper to the working group. In it, they proposed that a set percentage of corporate tax be ringfenced for the sector. This is an eminently sensible idea, considering the benefits accrued by companies from our education system. Corporation tax is currently performing exceedingly well according to the latest Exchequer Returns, with takings for the first nine months of this year coming in 44.2 per cent (1.21bn) ahead of projections. This has given the government some extra money to play with in the forthcoming budget, a situation that benefits the country as a whole.

Without trying to overly moralise the debate, this is money that’s already being paid by companies in the form of taxation. This is not asking for extra money from them. Rather, this is a place where the money for education should come from, as this corporate system is a direct beneficiary of the existing educational structures in Ireland.