There are few places one can visit on Trinity’s campus that are not anchored in history. Since its establishment in 1592, the College has been a staple of the Dublin cityscape and has played a role in countless events which now dominate Irish history. It has also been no stranger to conflict, even at an international level. The question facing the College is that which faces the country as a whole, how do we commemorate history appropriately, without always celebrating it?

it’s so important.

As we currently find ourselves in the middle of the centenary of World War I, the question of how Trinity can shed light on its role has been raised. Many in the college community may feel detached from the Great War, seeing it as an event far removed from the campus and College Green. Recently, however, much effort has been undertaken in acknowledging Trinity College Dublin’s contribution to the events of World War I.

As part of the Decade of Commemorations initiative, a project which aims to remember the Irish Revolutionary period from 1912-1923, including World War I, the 1916 Rising, and the fight for Irish Independence, the College elected to erect a memorial stone to recognise the 471 students, staff and alumni of the College who lost their lives in the First World War. The stone was unveiled to staff, students and guests on Saturday September 26th.

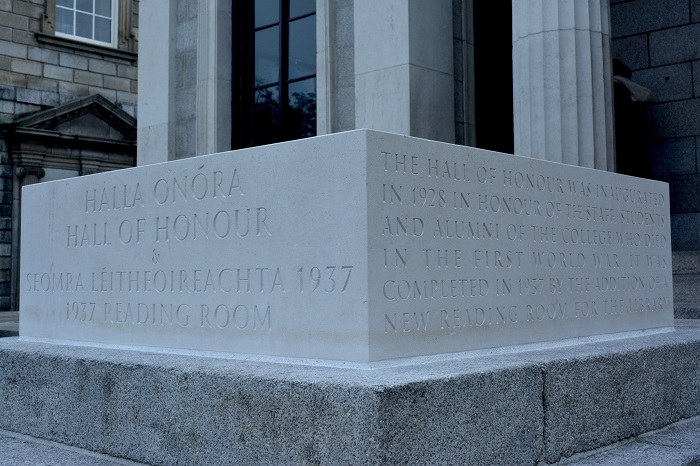

The monument, sculpted by Stephen Burke out of Portland stone, bears an inscription, written in both English and Irish, which reads: “The Hall of Honour was inaugurated in 1928 in honour of the staff, students and alumni of the college who died in the First World War. It was completed in 1937 by the addition of a new reading room for the library.” The appearance of the two languages side by side seems to reflect the coexistence of the British and Irish soldiers during this period of prolonged conflict of global warfare.

The stone is not the first memorial to Trinity’s dead. It sits atop the plinth in front of the Hall of Honour, within which there resides a list of all of those from the Trinity community who lost their lives during this conflict, called the Roll of Honour. It was unveiled back in 1928 and lists the 471 men who gave their lives while in military action.

While the College stresses the importance of preserving its history, this list of the dead is largely inaccessible. The Hall of Honour serves as an entrance to the 1937 Reading Room, a building which is used as a study room for Postgraduate students. With the majority of the college’s student population consisting of undergraduates, the record was largely invisible. At the launch of the memorial stone in September, Provost Patrick Prendergast on how Trinity’s role in the war is often forgotten and is often glossed over when we tell our history.

Unless you are willing to take the time to read its inscription and approach the monument closely, its nondescript appearance means you will likely view it as another piece of the college’s ubiquitous masonry.

This arguably explains the placement of the stone in Front Square. By placing it in one of the busiest areas of the campus, it could be said that the College is facilitating the renewed acknowledgment of those who fought in the war. That being said, the stone could be at risk of being largely ignored. Unless you are willing to take the time to read its inscription and approach the monument closely, its nondescript appearance means you will likely view it as another piece of the college’s ubiquitous masonry.

However, Dr Gerald Morgan of Trinity’s School of English, who notably campaigned for the erection of such a monument, welcomes the more prominent recognition: “The recognition of the World War One dead in the rededication by way of a memorial stone comes after many years of silence and even neglect” he told The University Times.

The 87 year gap between the inscription of the victims’ names, tucked away Hall of Honour, and the public unveiling of a more prominent memorial stone, is suggestive of schismatic Anglo-Irish tensions. This could mean that Trinity did not feel it could grant much in the way of official recognition to the those who were killed.

“The college remains anxious to avoid any suggestion that it is not an Irish university” says Dr Morgan, suggesting that the reason that there has been such little recognition of Trinity’s fallen, is due to the divisive Irish nationalism which has pervaded the country since the time of the first world war. But many felt that the 3,000 Trinity men and women who pledged themselves to the war effort, with a sizeable number losing their lives, deserved a location of prominence to their memory.

Interestingly, there are other figures of Trinity’s past that are afforded centre stage in terms of visibility. Not one hundred metres from the memorial stone sits a near unmissable statue of Provost George Salmon, who famously opposed the admission of female students to Trinity. Given that many Irish people saw their countrymen’s involvement in World War I as betrayal of the fight for Irish independence, it is not surprising that the College has not placed a monument to it front and centre. But it is almost as if a fear of igniting political tensions is seen as a much greater danger than the celebration of a man, who by modern standards would be considered a misogynist, and in fact limited the rights of others instead of fighting for freedom for all, which was likely the intention of many of the 471 who went to fight.

To some, the unveiling could be seen as a somewhat controversial move, given the lead up to the national commemorations of the 1916 rising, but as Provost Patrick Prendergast clarified at the unveiling, politics aside, the first world war had a profound effect on the college and as such has a rightful place in the college’s history. “Trinity’s war experience is part of the university’s history and the inauguration of the memorial stone will give further prominence to this past,” Prendergast said, emphasising that the monument remembers an event specific to the Trinity community.

Katie Crowther, President of the Graduate Student’s Union, expressed a similar sentiment. She told The University Times that she was honoured to take part in the ceremony and clarified that “to remember those who died is not to honour war or death but to honour those willing to risk their lives to protect life as they knew it.” Crowther also presented the idea for an online memorial, which could illustrate genealogical and geographical links to those honoured by the monument.

Jane Maxwell, a member of the Hall of Honour Memorial Stone Committee, called the ceremony “both deeply moving and dignified” in an email correspondence with The University Times. She echoed the sentiments expressed by fellow committee member Professor John Horne, a lecturer of Modern European History in Trinity, referring to the dedication as “’a kind of reparation’ for allowing TCD’s war service slip from memory in the 20th century.”

While the stone has clearly been erected to ensure that more people are aware of Trinity’s victims of the Great War, the Hall of Honour, which it guards, presents an interesting view into what kind of recognition different victims have been afforded. The gatekeeping monument serves as a general commemoration piece, but those lucky enough to have access to the 1937 Reading Room can gain a valuable insight into historical class distinctions which determined the prominence of the commemoration.

The inclusion of working class figures, such as George Marsh, in the accounts read at the unveiling of the memorial is perhaps an indication that Trinity is moving towards a more inclusive future, one where social stature has no impact on the treatment of a student, dead or alive.

While the list includes such esteemed figures as Ernest Julian, who was the Reid Professor of Law at the college, it also bears the names of working class figures. Three men of lower social order, all former staff members of the College, were not included in the original 1928 list, but added later. Their names appear in isolation. One of the three was George Marsh, who worked as a porter here before joining the war effort. The exclusion of his name adds to a list of discriminative actions of the College which only contribute to the idea that Trinity was an elitist institution, and is now making efforts to shake off this reputation. During the unveiling ceremony, Marsh was one of the profiles read out to the spectators. This is perhaps an indication that Trinity is moving towards a more inclusive future, one where social stature has no impact on the treatment of a student, dead or alive.

Marsh is not the only outlier honoured by the stone. While many remember the men who lost their lives, it is important to note that the casualties were not all male. Louisa Woodcock, who campaigned for the establishment of the Endell Street military hospital, has her name standing out among a sea of male counterparts. While little is known of the circumstances surrounding her death, we know that Woodcock lost her life during the conflict of 1914-1918. If anything, her name acts as a symbol for the often-forgotten participation of female figures during these considerable historical events. However, unlike Marsh, Woodcock’s social standing ensured that her name was included in the original 1928 list.

While certain victims of war have had their recognition delayed, it appears as if we are now at a stage where class and gender restrictions have been abolished from Trinity’s commemoration, in the case of this monument, at least. It is worth examining our government’s general attitude to remembering our countrymen who fought and died in the Great War of which Trinity’s commemorations play a part.

In recent years, both the Taoiseach and Tánaiste have attended Remembrance Sunday events in Belfast. In addition to this, Enda Kenny, together with British Prime Minister David Cameron, laid wreaths at the site of the battle of Ypres, where according to wartime information available on www.taoiseach.gov.ie, the Dublin Fusiliers were near annihilated in May 1915. The fact that detailed information of Irish involvement in the Great War is available on government websites proves that commemorating the sacrifice of our countrymen outweighs the potential of provoking conflict between those who supporting the Irish who fought and those who didn’t.

Regardless of warring opinion on the Irish who pledged their lives to the fight during World War I, Trinity has elected to ensure the preservation of its history. No longer does the threat of being labelled ‘West Brits’ impact the College’s capacity to commemorate members of its own community. This memorial stone was erected to ensure that all members of the Trinity community are given the opportunity to understand that the university did play a role in the war and to recognise the sacrifice made by those who gave their lives. It might not be the most arresting monument on campus, but its mere existence indicates the College’s commitment to commemorating its own.