Last night RTÉ launched their official 1916 commemorative suite of programming in the National Gallery. On arrival, I looked around at the stuffy, standard red and white wine reception, with salmon puffs and goats cheese on only-god-knows-what canapés: a set-up we have become all too accustomed to in our Silicon Republic of networking pageantry. Is this really what our forefathers, the rebels Padraig Pearse, Michael Collins, James Connolly and Sean McDermott had envisioned a hundred years after the Rising? A potpourri pot of guests around white-cloth pod tables, being handed commemorative 75 page booklets – which, if you judged by the cover, served to act as an informative and authentic source of history, but on the inside contained the RTÉ winter TV line-up? It appeared almost crass that the national broadcaster would gather people together and use such a historic and important event to pedal their own product, and toot their own trumpets about what an “excellent” public service institution they are.

And then the trumpets were literally brought out. When the Taoiseach arrived (almost an hour late, you may put a watch on your Christmas list, Enda) the brass section of the RTÉ orchestra emerged in one corner. The atmosphere in the room shifted in a barely perceptible manner, as everyone edged forward towards the small stage and fondled their iPhones, preparing to take snapchats of the fanfare.

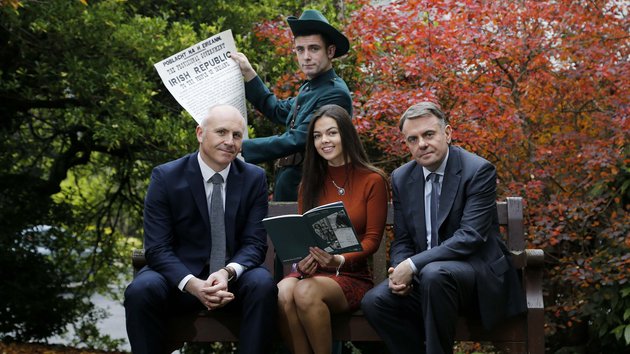

When Noel Curran, the Director-General of RTÉ, started to talk about his visit to the set of “Rebellion”, the new drama which will explore the characterisation of the events leading up to and during the Rising, my cynicism of what was unfolding began to weaken. He spoke of walking onto a reconstructed set of Moore Street, and noticing that one of the shops was none other than O’Hanlon’s Fishmongers, and remembering that his mother had worked in O’Hanlon’s as a 13 year old in the first half of the last century. He explained that this was an emotional and unexpected experience – visiting a TV set that was part of his mother’s real story, the story of the Rising – now RTÉ’s own coverage of those events. Curran predicted that such unexpected, personal connections are likely to abound next year.

For me, that sensation occurred when they played a few minutes of promo for “Rebellion” on screens. This was no lukewarm, mediocre, worst-episode of “Fair City” that many of us have come to subconsciously associate with the first channel on our television sets. This was more in the new, captivating “Love-Hate” genre of craft. Filmed in Collins Barracks, snippets of actors Brian Gleeson and Charlie Murphy flashed on screen. For about half a second, there was a shot of a scene filmed in Trinity. Front Square – a place we cross to get to lectures, where this newspaper is printed, where some of us call home this year, where we stumble worse for wear after the Pav kick us out as we begin our night on the town, where the Christmas lights will be turned on in a matter of weeks – is about 500 metres from the GPO, that still bares the scars of bullets from the fateful Rising. I was standing two metres from an Taoiseach, the leader of the Irish Republic for all his faults, when the goosebumps, I am slightly ashamed to say, appeared on my arms. Only a mere few steps away outside the National Gallery, Fenian Street sprawled out, where the rebels of Irishmen and Irishwomen had gathered. It was all very surreal.

It’s all well and good to paint your face green on St Patrick’s Day and get drunk, or cry like Ian Madigan watching when Ireland win a match, but if you express patriotism in the context of the Rising, you run the risk of evoking connotations of the subsequent Troubles – or even the negative association with the IRA. Furthermore, we are constantly being told in lectures across a wide range of disciplines of the wonders of globalisation, of the advantages of Ireland being a small, open economy at the mercy of the wider world, or of the increasing influence and dependency on the European Union in some cases. Nationalism has become a dirty word, a profanity contained for special yet fleeting, sometimes superficial, occasions.

In that beautifully architected room, where the old is so aptly melded in with the new, Enda Kenny spoke himself of the question “Who are we?” in the context of the Republic preparing to open a treasure chest of history. His answer? “We are part of this pageant”. Now, I don’t know if he was referring there to his government, the mishmash of guests in front of him, or the theatrics of a revolution that has lead us to the state we are in today. More than likely, whether he realised it or not, all of the above were invoked.

This gathering was not just an effort to rehash the facts that came to life over a hundred years ago, but an exercise in storytelling so all that is good and grand and great about this country can be brought to the fore. Do you know what? Fair play to RTÉ for putting together the drama series, documentaries, concerts and street gatherings that they have planned for 2016.