Politics is a dirty business. We are so often repelled by a modern political discourse, defined by trite platitudes and tit-for-tat score settling, that we feel compelled to look away. We greet politicians with suspicion, wondering what expensive meal we, the taxpayer, will have to fork out for next. In this epoch, Lord Acton’s belief that “power tends to corrupt and absolute power corrupts absolutely” seems to have become a truism. But could this Power, with her honest, no-nonsense approach, be the much-needed alternative?

Senator Averil Power is one of Ireland’s leading political voices. This young woman, from a working-class background, serves as something of an anomaly in the Irish political landscape – one buried in the traditional beliefs of ageing, middle-class, white men. No party better encapsulates this traditionalism than Fianna Fáil. So, one may wonder, why did Power join this party to begin with? And why did she take so long to leave it? Did she do so because she perceived an ambivalence on Fianna Fáil’s part to back the marriage equality agenda? Or, did she make the break in a bid to make her star shine brighter in the political circuit?

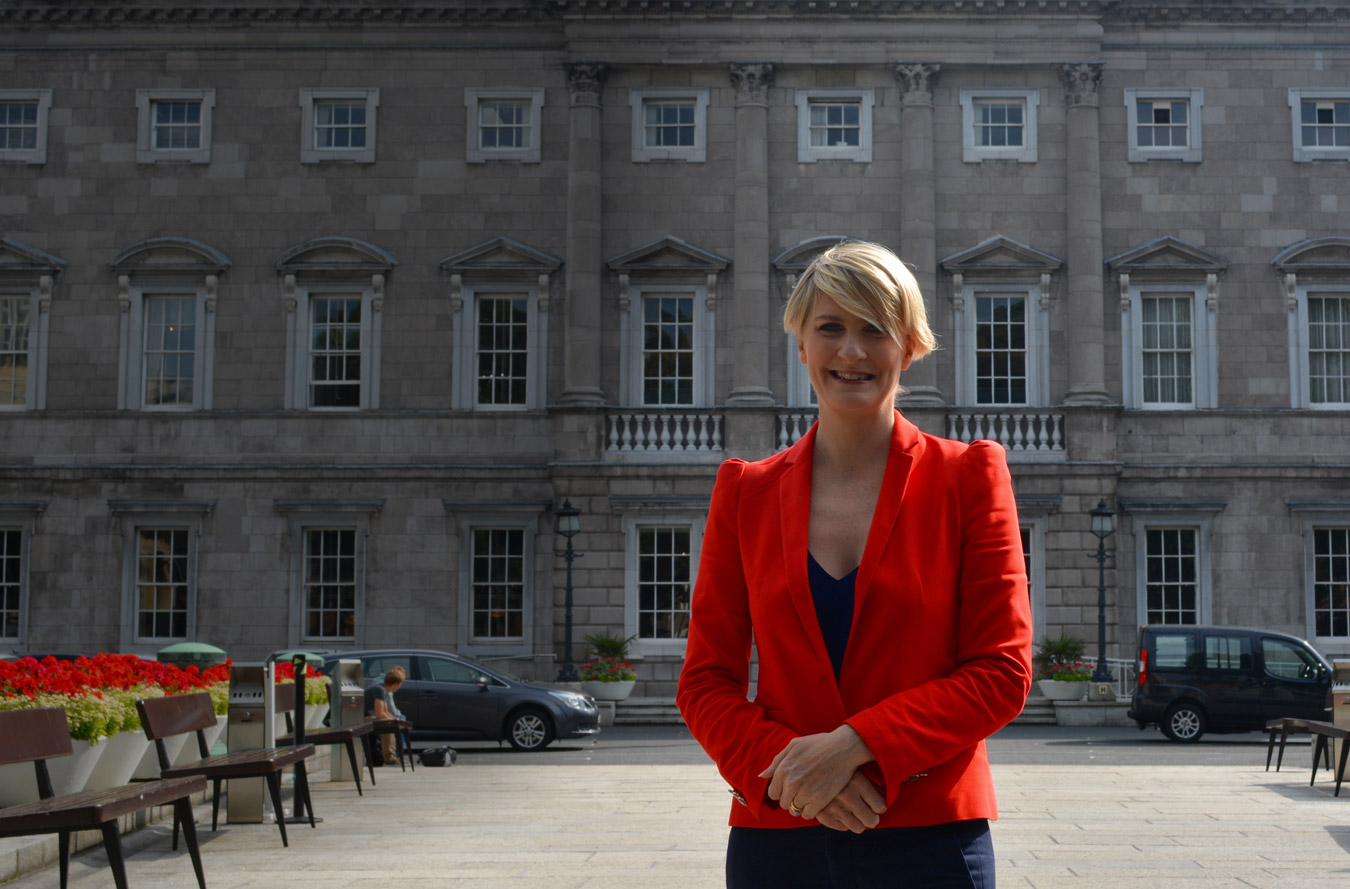

I was determined to ask Power the tough questions and demand answers. Here, amongst the grandiose setting of Leinster House, I was greeted by an ordinary person with an extraordinary drive for social justice. The result? A refreshing and candid conversation, which, at times, felt much more like I was speaking to an activist than a politician.

“just two months after being elected in 2011, I called for Bertie Ahern to be kicked out, a year before he was”

Averil first sought office for Fianna Fáil in 2009, when Ireland was in the grip of a crushing recession. But what attracted her to the party that was, to most, partly responsible for the economic catastrophe that engulfed this country? “I joined the party while I was studying at Trinity”, she says. “Fianna Fáil, with its strong history in education, appealed to me. When I ran for election in 2011, I really had to think if I even wanted to run for Fianna Fáil. I wasn’t happy about a lot of the decisions that had been made. It was obvious that Fine Gael and Labour were going to have a huge majority and I felt it was important there would be a strong opposition. From a personal point of view, I felt this opposition shouldn’t be Sinn Féin. You need a strong, sensible opposition that would hold the government to account”.

Power left Fianna Fáil in May 2015, saying the party lacks “vision, courage and leadership”. And this wasn’t her first time to publicly condemn the party: “just two months after being elected in 2011, I called for Bertie Ahern to be kicked out, a year before he was.”

“That didn’t endear me to everybody”, she laughs, “but I’ve always been outspoken and upfront”.

“Look, I wasn’t happy about where the party was but I did feel there was a lot of decent people involved. After a series of issues that were constantly rebuffed by Micheál Martin, I eventually felt that Fianna Fáil just didn’t want change.”

Power is now an independent senator and will run in the next election in the Dublin Bay North constituency, an area she deems the most competitive in the country. She admits leaving Fianna Fáil wasn’t easy: “I didn’t know what I was going to do next, but I just knew in my gut that I couldn’t stay. I was really angry about their response to the marriage equality referendum. They were trying to be on both sides, which I found deeply cynical”.

“The referendum showed politics at its best – what’s possible if you believe in something and you work hard to ensure you get it. The referendum was about a lot more than just gay rights.”

Averil was a strong supporter of the marriage equality referendum from the get go. She canvassed 35,000 houses during the campaign. “The referendum showed politics at its best – what’s possible if you believe in something and you work hard to ensure you get it. The referendum was about a lot more than just gay rights. It was younger people taking control and pushing for their vision for a better society. We never really found our feet as a modern, progressive country. There’s a lot of people in Leinster House who have been here too long. They don’t think they can change anything. The last few years have been really tough but we have to re-find our energy and work to make things better. A lot of that involves people getting involved in politics again and shaking up the system”.

If there is anyone to shake up the system, it’s Power. Just before the summer recess, the government brought forward her proposed bill to end discrimination against gay teachers and doctors. Until now, one could be discriminated against by church-run bodies, which means 95 per cent of our primary schools and most of our hospitals – because they’re under Catholic patronage. In theory, they could have refused to hire someone or deny them a promotion on the grounds that it was a threat to this ethos, which mainly affects those who identify as LGBT. It’s difficult to believe such legislation is even up for discussion but, it took three years to get Power’s bill passed. “Things take time and that can be frustrating. I was upset when it didn’t pass in 2012. I was getting emails and letters from teachers who were affected by that – particularly in rural Ireland.”

In many respects, Power is a refreshing antidote to the stereotypical elite who seem to run this country. She grew up in a council estate and was the first person in her family to sit the Leaving Certificate. She felt a compulsion to attend Trinity College. Having duly accepted a place in BESS, she was initially struck by her outsider status.

“At first, I found it really uncomfortable. I didn’t know anybody. There were twenty people from Michael’s, twenty people from Loreto on the Green. Everybody had their groups from all the different private schools and I kind of felt like an outsider. I felt like everyone was looking at me and thinking ‘how did she get in here?”

Undeterred, she immersed herself in college life and began to flourish. Rather than savour these newfound opportunities and accomplishments, Power couldn’t help but feel aggrieved that so many people from her background had been denied access to tertiary education and its attendant benefits.

“The more that I started to settle in and enjoy college, the more I became aware of the fact that there were opportunities opening up for me that my brothers, parents and friends would never have. I found that deeply unfair. It’s not that they weren’t as smart as me, it’s that they didn’t get the same opportunities as me.”

This sense of social justice and the need for a more egalitarian society ignited her interest in politics. Indeed, it still characterises her politics and colours her discourse. “That’s what’s driven everything I’ve done since – my passion for education, my interest in LGBT rights and women’s issues. I suppose just any form of inequality annoys me. I think everybody should have the same opportunities in life, whether you’re gay or straight, rich or poor, male or female, black or white. I would like to do everything I can to make that possible for people”.

Determined to find an outlet for political expression, Power joined Trinity College Dublin Students’ Union, eventually rising to the rank of President in 2001. She entered the role with naive exuberance, but soon became attuned to the power struggles and conflicts within the union and the campus as a whole. It was, perhaps, her first exposure to realpolitik. “There are some people that will pull against you for the sake of it. When I first got involved in student union politics, I was totally naive and very agreeing. It was tough at times. I learnt some great lessons from it – you’ll always have to deal with negativity. It was an amazing experience but it was also scary”.

In clear, painted, artistic form hung all of our past leaders – everyone from Charlie Haughey to WT Cosgrave. There was something strikingly similar about them. They were all ageing, middle-class, white men.

One particularly testing encounter involved a very public disagreement with Lucinda Creighton, now a TD for the newly formed Renua party. Creighton, who then led a pro-choice group within the college, was vocally critical of Power’s refusal to endorse a pro-choice stance in a student abortion referendum. Facing vociferous criticism, Power stood her ground and refused to take sides.

“It got very personal against me. I never gave a view one way or another, in favour or against. It was difficult personally and it was upsetting, but it also taught me a lot about resilience and that is something that has stuck with me to this day”.

In this instance her refusal to take sides was informed by personal circumstances: “In terms of abortion, as someone who was adopted myself, it’s not a black and white issue. I was an unplanned pregnancy. I’m glad my mum made the choice to keep me and have me adopted. It’s an emotional issue for me”.

However, Power still supports abortion from a human rights point of view: “After Savita Halappanavar’s death, I was the first politician to call for legislation, but it was nine months before it was brought through. The government are blind to women’s pain and unprepared to act. I felt there was a real lack of courage on behalf of the government. If there’s a coalition to repeal the 8th amendment, I’d absolutely support that”.

85 per cent of the TDs in the Dáil are male. Is this causing the outdated attitude towards women’s issues? Are quotas, like Norway, the only way to drive change? Power reluctantly agrees: “I think they’re a necessary evil. They’re symptomatic of a broader failure. Unfortunately, I’ve lost faith in the system changing by itself. Women need to believe that politics is something they can do”.

Upon finishing the interview, Power brought me on a tour of Leinster House. We chatted and continued sharing our views on various social issues. However, it wasn’t until we were surrounded by the portraits of past Taoisigh that I truly realised the extent of what she was talking about. In clear, painted, artistic form hung all of our past leaders – everyone from Charlie Haughey to WT Cosgrave. There was something strikingly similar about them. They were all ageing, middle-class, white men. When will our tired circle of politics be injected with fresh, vibrant ideas? Perhaps Power is just the woman to shake up the powerful. Watch this space.