Anyone who enjoys reading will know that there is far more to it than just words on a page, presented in a systematic yet aesthetically pleasing manner. However, it is often easy to overlook the power and scope that such an act can have, and oversee the responsibility that we as readers have been entrusted with. It is important to acknowledge the larger moral and political complex that the reader enters into when they pick up a book. So too is it necessary to acknowledge ways in which literature works as a vehicle for the progression of human rights, from the dawn of the novel in the 18th century to beyond. Reading brings the plight of others into our immediate world, telling us about the suffering of people who seem more like us with every page turned. Indeed, reading in turn gives us the capacity to grant others the rights that we are lucky enough to have already.

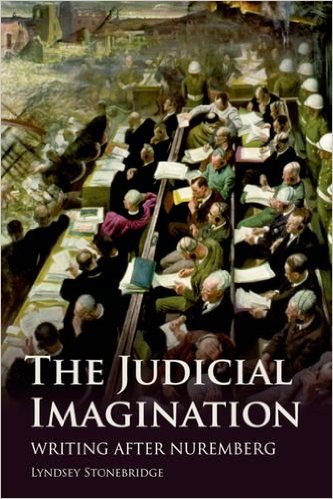

“The Judicial Imagination”, a book by Prof Lyndsey Stonebridge, Professor of Modern Literature at the University of East Anglia, traces underlying critical judgments in works of post-war writers and intellectuals. It features notable writers Rebecca West, Elizabeth Bowen, Muriel Spark and Iris Murdoch. Addressing the Royal Irish Academy on the 22nd October, Prof Stonebridge highlighted the ways in which her book acts as a medium between the worlds of history, law and literature to illustrate how the novel can articulate moral, philosophical and political questions. In the book, Stonebridge investigates the ways in which writers of the twentieth century navigated issues of statelessness, exile and migration. The book also looks at the cultural and historical influences on the growth of human rights, to the position that they are in today. “The Judicial Imagination” presents the reader with a new way to consider human rights. It reflects upon what we already imagine human rights to be, in contrast to their greater potential. Stonebridge suggests that the immense history of revolutionary movements, prior to the twentieth century reflected in literary revolutions of that time. She proposed the idea that how we read and what we read is intrinsically linked to our understanding of what human rights really mean to our immediate environment. With this in mind, Stonebridge considers the impact of the greatest atrocities of the twentieth century on human rights movements, and the problems encountered upon making efforts to form a new kind of justice.

At a time when human rights seem to be failing those who are in desperate need of their administration, Prof Stonebridge encourages her readers to question how reading and writing on the topic can eventually translate into direct action. Her book encourages the ongoing commitment to the question of the representation of human rights, and in turn, forces us to wonder how the current humanitarian crisis that engulfs Europe will be represented in centuries to come.