If we are going to have a discussion about loans, there are a few points that are worth clarifying. To begin with, there are at least two fundamentally different kinds of loan schemes. The first, which we will call a “support” loan, is designed to help a student cover the cost of third, and in some cases, second-level education. The second, which we will call the “funding” loan, is designed to provide for the cost of funding the system.

As a student in the support model, you are the primary concern. This model is often accompanied by generous grants and supports from the state. Additionally, there is typically low or no tuition fees in countries with these kinds of loans.

As a student within a funding loan system, you are not the primary concern – your institution is. This system identifies and treats you as a service user. Your participation in the system can and does generate revenue for the sector, thus easing the burden elsewhere.

The philosophies behind the two funding models have an impact on both the cost of your education and the kind of education you might receive. In a funding model, the economic value of education is one of the primary values, and as such, courses that provide for more lucrative careers are prioritised over those that don’t.

As a student within a funding loan system, you are not the primary concern – your institution is

It is the funding loan system that has dominated the conversation in Ireland for the last number of months, and there are a number of difficulties with this kind of loan scheme.

Firstly, a funding loan system won’t generate enough revenue without a significant increase in the fee. Based on the projected needs of the system, we would have to increase the fee by €5,000 per student. This would provide what has been described as the minimum requirement for the system to function. This would mean students would have to borrow €32,000 just to cover tuition.

Secondly, the risk of emigration is understated. Projected defaults as a result of emigration are in and around 18 per cent. This figure has been arrived by looking at Australia and the UK, both dominant economies in their regions.

Thirdly, the risk for the state is significant. We would only begin to repay when we have salary we cannot be reasonably expected to earn until we are at least 3 to 4 years out of college. Increasing the cost of fees means increasing the risk for the state. The UK have had to accept that a £9,000 fee is likely to cost the state more than when the capped fees are at £3,000.

In addition to some of the operational problems, there is the fact that loans will essentially try to wring the last few drops out of students and their families when funding could much more easily be sourced elsewhere.

At €3,000 we currently have the second-highest fee in the EU. Only the UK has higher tuition fees, with the exception of Scotland which is tuition free. Even in the context of introducing a loan scheme the scope for increasing the fee is limited both practically and politically.

Meanwhile, Ireland places 29th of 32 in the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) for third-level expenditure per student. The state contribution is below the OECD average and the employer’s contribution is essentially non-existent. All of this would appear to be counter-productive in an economy so heavily reliant on a highly educated work force.

Furthermore, there is something frustrating about the idea that the answer to our financial woes is to significantly increase the cost on one group while simultaneously taking the stance that it is unreasonable for other stakeholders to make the average contribution.

The idea that free education is blue sky thinking on a continent where it is the norm is quite strange

For example, if employers’ PRSI was to be increased to EU average levels, it would generate an additional €8 billion per year. However, conversations on increased PRSI contributions are focused on the fact that it would be unfair to introduce such a measure. What about the student who has faced a 240 per cent increase in the cost of college registration fees over the past number of years?

Funding loans in Ireland will not address the funding issue at third level. Not only are they unworkable, but they are also unfair. The idea that free education is blue sky thinking on a continent where it is the norm is quite strange.

However, the idea that a state and industry that relies on highly skilled workers for growth and prosperity cannot be expected to make what is an average contribution is not only beyond unreasonable, it is exploitative.

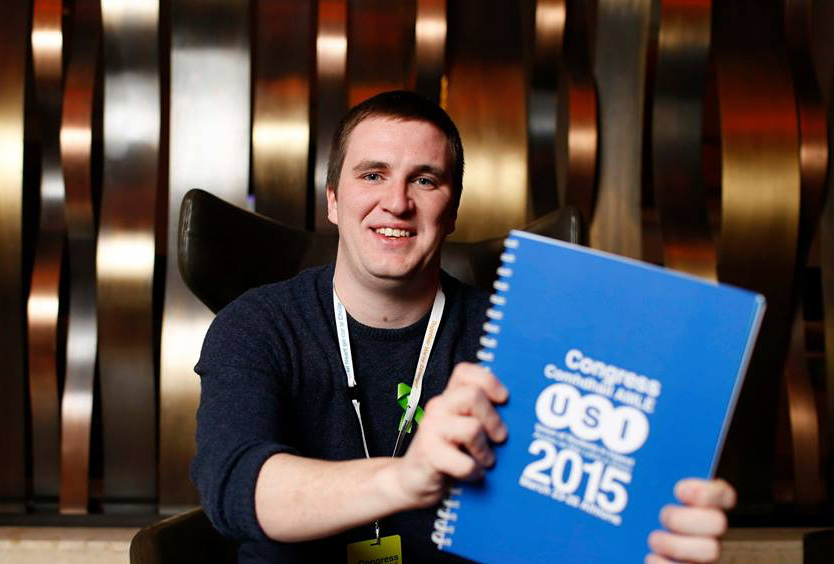

Kevin Donoghue is President of the Union of Students in Ireland (USI).