The Royal Irish Academy’s report, submitted to the government higher education funding working group and published earlier this month, puts the academy considerably out of step with all the major parties with regards to higher education funding, none of whom have committed to any new funding model for third-level education after the election. Since the funding question did not permeate the debate during the general election, there is potential for it to become an issue during the negotiation of programs for government.

In the report, the academy insisted that the present student contribution of €3,000 should be replaced by the imposition of fees for the full cost of tuition on students. The report also recommends an income-contingent loan scheme whereby students will be able to borrow money from the state to finance both the payment of these fees and maintenance costs. This report, complete with recommendations from the academy, is the latest development in the current state of uncertainty of the future of university funding.

This engagement with the difficult question of how to fund higher education is in keeping with the academic tradition of the academy.

Founded in 1785 by James Caulfield, Earl of Charlemont, the academy received the benediction of a royal charter the following year. Though it was originally housed on Grafton Street, the academy now occupies Academy House, a mid-eighteenth century premises on Dawson Street, right on the doorstep of students strolling out of the Arts Block.

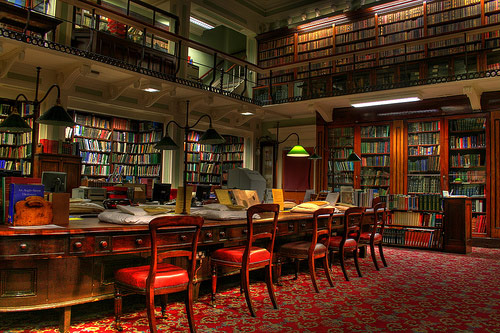

This building currently houses their library and extensive array of antiquities and manuscripts, gathered from both donations and smart purchases over the last two centuries or so, a collection which has remained impressive despite notable relics as the Ardagh Chalice and the Tara Brooch having been transferred to the National Museum of Ireland. Indeed, speaking to the The University Times, Treasurer of the Royal Irish Academy, John McGilp, who is also a professor in physics at Trinity, stated that the academy “holds the largest collection of manuscripts in Irish in a single repository”, a collection that includes the sixth-century Cathach, the oldest surviving manuscript in Ireland, as well as the second oldest latin psalter in the world.

Their recommendation of an income-contingent loan scheme to funding higher education puts them squarely in opposition to the Union of Students in Ireland

“It was a place with the makings of the National Museum” notes Prof David Dickson, member of the academy and history lecturer in Trinity. Speaking to The University Times, Dickson emphasises that the academy is “older than the state, the National Library of Ireland and the National Museum”.

Membership of the academy is in itself an impressive achievement, with only 16 of the island’s most brilliant academics elected each year by current members. The academy elects members from both Northern Ireland and the Republic, with international recognition and notoriety of one’s academic work acting as essential criteria in the selection process.

The academy’s long history has seen it forge strong links with Trinity, with many of the university’s most eminent students having attained membership of the academy. William Rowan Hamilton, the renowned mathematician and namesake of the building frequented by students of science and engineering, was made president of the academy in 1837. In addition, the physicist John Lighton Synge and the Nobel Laureate Ernest Walton were also elected to the academy. Edmund Burke, one of Trinity’s most famous graduates, was granted honorary membership, an accolade conferred by the academy on reputed scholars not ordinarily residing on the island of Ireland. Susan Denham, Chief Justice of Ireland and Trinity graduate, and the first woman to be appointed to the Supreme Court, is among the illustrious list of current members.

The academy is noteworthy in the way that, since its foundation, it has been of a markedly interdisciplinary character, encompassing experts in both the humanities and the sciences. “The [academy] is distinctive in that we are an all-Island body, working across two different jurisdictions”, according to McGilp, adding that “we represent all areas of scholarship”. Indeed the presidency of the academy, which is currently held by Prof Mary Daly of University College Dublin (UCD), rotates between academics of the humanities and sciences every three years.

Similarly, the Council, which bears much of the responsibility for the organisation’s governance, is composed of an approximately equal balance of scholars of both the humanities and sciences. “It’s a unique collection point for people in the sciences and in the humanities and social sciences,” says Dickson, adding that “the representation of the humanities and mathematical sciences is particularly strong”.

In addition, Dickson states: “While the senior academics or retired academics that make up the academy don’t necessarily represent the whole academic community, what goes on in the academy is a lot more all-encompassing”. For example, lecturers can obtain permission for their undergraduate and postgraduate students to access the library’s unique collection for specific research purposes. Beyond that, the academy often works in collaboration with non-member academics in seeking broader perspectives and input on research ideas – funding archaeological digs in Ireland, for instance. Multidisciplinary committees are also a core feature of the academy, bringing together experts from a range of interconnected fields to draft policy documents and advise the institution on possibilities for future research projects.

This multidisciplinary aspect of the academy is also evident in the research projects that it conducts, such as the Clare Island Survey, which offers very significant findings in the fields of archaeology, history, geology, biology, and conservation. Indeed, the academy is not an inward-looking organisation that merely recognises the best Trinity academics. Instead, it is not afraid of committing itself to distinctive research goals.

For example, the academy has worked to produce a number of online academic databases such as the Dictionary of Medieval Latin from Celtic Sources and a Historical Dictionary of Modern Irish. The latter is a project that is particularly distinctive. Speaking to The University Times, Déirdre D’Auria, who has worked on the project for over ten years and who has just completed her term as staff representative on the Academy’s Executive Committee, said: “This is a historical language dictionary, descriptive, rather than prescriptive”. The project, “instead of simply providing a definition for a word, or a translation”, plans to trace the development of the word back to its earliest usage in modern Ireland. D’Auria describes it as “a vast project, requiring a long-term commitment”.

The academy has also co-ordinated research projects that have culminated in very significant scholarly publications, such as a five-volume Art and Architecture of Ireland and the classic legal text Origins of the Irish Constitution 1929-1941 by Gerard Hogan.

One of the more fascinating programmes undertaken by the academy is undoubtedly the “Scientist and Oireachtas Member Pairing Scheme”, which matches public representatives with scientists active in Ireland. Explaining the value of this project, McGilp said: “This collaboration aims to brief elected representatives on the world-class research that is currently taking place in Ireland, strengthen the role of evidence based research and enrich debate in public policy formation.” The academy then not only pursues knowledge for the sake of pure scholarship alone, but rather tries to make that knowledge available to the public and to the government.

Perhaps the most fascinating thing about the work of the academy is that while these projects are co-ordinated by small groups of salaried individuals in the academy, much of the content is produced on a pro-bono basis by various academics from different universities across Ireland. There is a dedicated, long-term focus to the academy’s work, as is particularly evident in the Dictionary of Irish Biography, a resource compiling information about notable people born in Ireland and the Irish careers of those coming from elsewhere. Dickson, who wrote a number of entries to the database, recalls that this was a “big collaborative project”, now comprising accounts of almost 10,000 Irish lives that “began in the 1990s but was only published in 2009, with much of the work being done by outside researchers but conducted by a small team in the academy.”

The academy is thus an entity with a central stake in higher education. Indeed, it is funded through the Higher Education Authority, much like universities, with much of its membership holding leading positions in Irish academic circles. This would make its assessment of the crisis in third-level funding and its proposed solution worthy of note, particularly given the individuals involved in drafting the report. The group was chaired by former provost of Trinity College, Prof John Hegarty, and among its members was Dr Mary Canning, a member of the Higher Education Authority and consultant for the OECD and the World Bank.

McGilp claims the academy feel “a responsibility and a duty to ensure that the quality of the higher education system is maintained to the highest standard”. In this respect, their contribution can only be positive, and may counteract the very limited engagement with these issues that has been apparent on the part of the political parties during the election.

The perspective they offer, though undoubtedly imbued with expertise and rigorous research, can perhaps be regarded as a lecturer’s or academic’s perspective. This perspective is one that is in ways very different from those of students. This is clear from their recommendation of an income-contingent loan scheme to funding higher education, a proposal that puts them squarely in opposition to the Union of Students in Ireland (USI).

However, prior to the publication of this week’s advice paper on higher education funding, such focused input on the public debate has been largely absent. Prof Dickson notes that the academy “hasn’t until now been involved in theorising how the Irish university should be”, acknowledging that in recent years “it’s been much more committed to outreach events and policy documents”.

This new attempt at lobbying on the funding of higher education marks perhaps a more assertive chapter for the academy. However, this new role begs the question: is the third-level sector, and indeed the public at large, best served by an elite academic institution that takes such a determined policy stance on an issue so contentious as student fees?

For Dickson, the academy should play a more neutral role. He suggests that “the academy is at its best when it’s showing what the arguments are rather than taking a specific position or being unduly prescriptive”.

The academy could say things that it would be difficult for all of the cultural institutions to say collectively, but which would nonetheless be useful to add to the debate

This desire to see the academy act as a neutral forum for debate is also shared to an extent by Head of Trinity’s School of English, Prof Chris Morash. Speaking to The University Times, Morash, who is also a member of the academy, said: “The academy provides a platform from which it is possible to take a wider view of issues relating to Irish culture, Irish education, Irish science, or any of the other areas in which members have expertise.” Morash acknowledged however that “pure neutrality is not always possible”.

However, McGilp takes a different view, suggesting that the very specific conclusions present in the report remain constructive because the academy is “independent and unbiased”, approaching the issue of funding for higher education “without having a predetermined position”.

It seems to be the case that in co-ordinating the input of academics from all Irish universities, the academy may be able to aggregate the views of the third-level sector as a whole. Regarding his own experience in the drafting of policy documents for the academy, Morash suggests that “the academy could say things that it would be difficult for all of the cultural institutions to say collectively, but which would nonetheless be useful to add to the debate”, adding that, “the same is true of the policy advice on the funding of higher education”.

Ultimately, the emergence of a strong and authoritative voice on the issue of higher education and its funding perhaps ought to be regarded as a positive. As has become apparent from the total failure of the leaders of the major political parties to address any issues regarding education, the crises in the funding of higher education are not a priority for the political establishment. The academy, if it continues this more vocal attitude, may yet change this.