Over the past year, we have seen a gradual increase in people not being afraid to say the words, “I am a feminist.” The prime minister of Canada, Justin Trudeau, is a proud feminist, declaring that, in 2016, people should not be afraid of the word, while countless other influential names in the media have also come forward and said that they, too, are feminists.

But what about students? Students have always had a hand in activism, and Trinity is known for having a liberal-leaning population who are passionate and educated about social justice and global issues. Groups such as Fossil Free TCD, Students Against Fees, and multiple political party-affiliated societies all receive significant support. Alice MacPherson, deputy AHSS Convenor, who was heavily involved in the Women in Leadership campaign last year, notes that, because of this “liberal bubble”, there’s a “danger” of thinking that feminism isn’t a real issue to be addressed beyond the university. She feels that this would be “missing the point” of the fight for gender equality. So where, then, does feminism rank in priority for the average Trinity student?

Feminism, by definition, is the desire for the advancement of gender equality rather than a desire for one gender to be above the other. Speaking to The University Times, Seanad candidate and Reid Professor of Criminal Law, Ivana Bacik, describes feminism as “ending discrimination against women, and the recognition of the need to address harmful discrimination”. Identifying as a feminist is something that is unique to each individual, while at its core remains about equality.

The term “feminist” has become associated with an image of a bra-burning, screaming misandrist. For example, over 20 British universities banned Robin Thicke’s “Blurred Lines” from being played on campus, claiming that it promoted rape culture and misogyny. These decisions have been criticised as hysterical and hypersensitive. Online, “men’s rights activist” groups have grown in prominence, indicating the slow and reluctant growth in universal feminism. These groups accuse the feminist movement of harming the rights of men and influencing society negatively, reducing feminism to tongue-in-cheek “male tears” coffee mugs. However, many claim that feminism is not and should not be synonymous with hatred for men. “I don’t define it as ‘revenge’”, explains MacPherson, adding: “People seem to think that feminism means it’s specifically female, [that] it’s only about women clawing themselves up above men.”

Identifying as a feminist is something that is unique to each individual, while at its core remains about equality

What, then, does feminism mean to Trinity students? For Gender Equality Officer of Trinity College Dublin Students’ Union (TCDSU), Louise Mulrennan, feminism is about confidence and empowerment. Speaking to The University Times, she says: “It gives people a lot of courage, being part of a movement. You don’t feel like you have to face and tackle these issues on your own.” Having launched a Humans of New York-style campaign called Feminists of Trinity on March 29th, Mulrennan emphasises the need to use feminism in a “positive way” to address the social conditioning that has made inequality so inherent in society. She believes that, through this campaign, she can show the diversity of feminism in the university: “Sometimes feminism can be associated with so much negativity, so I think feminism is really important in college to have it as a positive term, and a pro-active movement.”

The diversity that Mulrennan hopes to show through her social media campaign is a topical subject, as the lack of diversity in feminism has become a common criticism. Campaigns, such as Emma Watson’s HeForShe campaign, and women, including Lena Dunham and Taylor Swift, have come under fire for endorsing “white feminism”, an accusation of being primarily concerned with the needs and wants of middle-class, caucasian and cisgender women. This is a danger within Trinity, too, which has yet to shake a reputation for being dominated by upper-class and wealthy students.

However, as Bacik points out, College is aware of this, with the Privilege Walk event, hosted by TCDSU and the Trinity Access Programme (TAP) on April 5th, aiming to address the issue of privilege. She says: “I do think Trinity has a very proud history of working on broader issues, particularly for disadvantaged women.” Bacik, a former TCDSU President, was taken to court during her presidency by the Society for the Protection of Unborn Children for providing students with information on abortion, something that was inaccessible to Irish women at the time.

The Privilege Walk aims to increase awareness of the power of privilege in society, whether it is based on gender, race, class, or sexual orientation. As someone who considers himself a male feminist, TCDSU President-elect Kieran McNulty is acutely aware of the concept of privilege, and how it can be “difficult to confront your own privilege”. However, he believes everyone should consider themselves a feminist, no matter what gender. Speaking to The University Times, he points out that, while it may not be as “intrinsic or vital” to someone who’s not directly affected by feminist issues, “it’s important as a member of society” to support the fight for gender equality.

McNulty proposed a motion at a TCDSU council meeting on January 26th to introduce mandatory consent workshops, and believes that the difficulty is not in saying you’re a feminist, but in acting on it. He points out that opportunities are “more limited” for those from lower socio-economic backgrounds to be involved in feminism in the university if they have to work part-time or have to commute to College, and are unable to be more involved with feminist campaigns through TCDSU or societies such as Gender Equality Society.

This is something that MacPherson agrees with, and she argues that, while people can’t “escape” their privilege, they should make an effort to do what they can for “others around us”. She believes there has been progress in Trinity on this, through programmes such as TAP. “As we promote these”, she explains, “the fight for gender equality ties into that, as the university comes to be representative of Ireland as a whole.” Mulrennan strongly agrees: “We should harness our education, harness the media attention that we can receive to further promote gender equality and to further work toward the cause.”

McNulty points out that opportunities are “more limited” for those from lower socio-economic backgrounds to be involved in feminism in the university

MacPherson was on the working committee for the Women in Leadership campaign alongside Mulrennan last year. The aim, in her view, was “instilling confidence” in female students about their ability to perform in positions of power. With four female officers on the outgoing sabbatical team, it appeared to be a successful campaign, having created a “culture” for women to thrive in. “It’s very much unseen, the lack of confidence a lot of women have,” she explains, “and they don’t directly associate it with the fact that they’re a woman.” However, with only one female sabbatical officer for the upcoming year, there is clearly still some way to go in terms of gender equality within positions of power in Trinity, something that Bacik notes is also a concern for women in senior academic positions in the College. McNulty believes that this is not because of “a lack of suitable female candidates,” but rather people not realising that gender inequality cannot be “tackled in one year”. He says he wishes to further promote the Women in Leadership campaign next year.

To define what feminism means for over 15,000 students is a near impossible task. “Not all students have a homogenous view on abortion, or things like that”, muses MacPherson, “but even if you’re against those things you have to speak up and let your voice be heard.” That is the beauty of feminism in her eyes, as she goes on to state: “What difference does it make to me, as long as women have the choice to live their life as they please?”

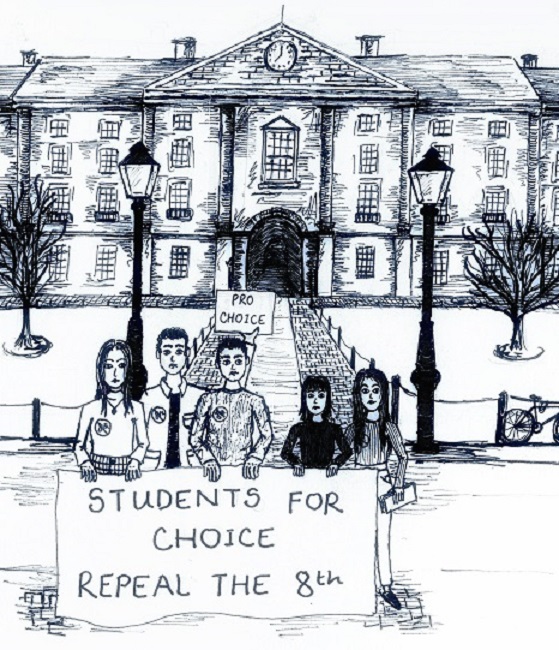

This emphasis on freedom and inclusivity is something that embodies the spirit of feminism, a movement that “attacks the status quo”, according to McNulty. And as we see students speaking out on how they feel about feminism, through the Feminists of Trinity campaign, the repeal the eighth movement, and even the Yes Equality campaign, we are reminded of the power of the student activist. “Young people and students,” Mulrennan states firmly, “we have so much power and we really need to use it, and work together.”

Feminist and political activist, Gloria Steinem, once said: “A feminist is anyone who recognizes the equality and full humanity of women and men.” There are students who identify strongly as feminist. Yet there are also students who do not. This is not usually a case of somebody being a “raging misogynist”, as MacPherson explains, but rather a lack of education on privilege and equality, which makes these conversations, the discussion on the need for consent workshops, the need for more women in positions of power and the need for greater accessibility so important for students to have. By starting the conversation on what feminism means to Trinity students, and who feminism reaches out to, students can begin a process of creating a more just and equal society for our own, and future generations. “Feminism can mean so much to so many people,” enthuses Mulrennan, “and we just need to continue talking about it, not be scared to use the word, and to be seen to be out there fighting for gender equality and promoting and advancing it in College, and in the world.”