Nestled across the road from Trinity, the Bridge21 programme looks at supplementing current teaching methods that often leave children unprepared for our rapidly changing society. Bridge21 was started nine years ago by Prof Brendan Tangney of Trinity’s School of Computer Science and Statistics, who acts as the programme’s principal investigator. A collaborative project run between the School of Education and the School of Computer Science and Statistics, it began under a different name. “It was originally called the Bridge to College programme”, explains Kevin Sullivan, Education Manager at Bridge21, speaking to The University Times. “It was a student programme for transition year students, where they would come in, spend some time in university and get a taste for it.”

They began working with Trinity Access Programme (TAP) schools – schools that typically have low progression rates to third level – and invited students to do workshops and activities with them. “They worked in teams, and they did projects, and they edited videos and recorded sound and made websites and all that stuff, and they went back to school very happy with their experience.” From there, Bridge21 started working with teachers too to enhance both the learning and teaching experiences in Irish education, “trying to take the way we work here and get teachers to do that in school and to introduce 21st century skills into second-level teaching”, continues Sullivan.

Whiteboards encourage teamwork because if everyone has a marker they can write down what they want, and people aren’t afraid to make mistakes because they can rub away whatever they want to

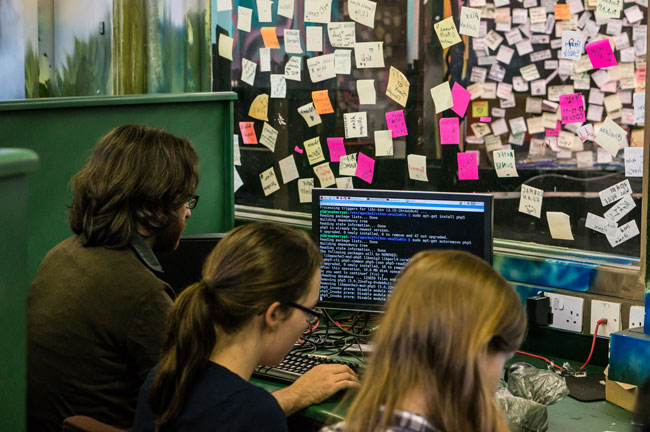

Bridge21’s facilities don’t resemble traditional learning spaces. The walls are painted as colourful murals. One room boasts a city skyline on all four walls, while the other has a green and leafy forest. The forest plays host to most of the computers in the facility, which can be found in individual spaces known as “pods”. The walls are covered in thank you cards and sticky notes. Each student who goes through Bridge21 writes their name and leaves it on the wall. “Returning students love to come back and find their names, it’s a nice little tradition”, says Sullivan. One room has numerous whiteboards on the tables to encourage teamwork and storyboarding. Especially with the rise of the internet and pretty much everything going digital, some companies may have forgotten about the traditional whiteboards, as there are no interactive whiteboards available. But with it being as simple as buying whiteboards, cloths and markers from sites like WRITEY, there shouldn’t be any excuse as to why someone as simple as using whiteboards cannot bring the team together again and increase interactivity.

“We find the whiteboards encourage teamwork because if everyone has a marker they can write down what they want, and people aren’t afraid to make mistakes because they can rub away whatever they want to.” The place itself was designed, explains Tangney to The University Times: “a) to support the scope teamwork model and b) not to look like school because we’re dealing with kids who wouldn’t necessarily have had a lot of positive experiences with school.”

Over the last number of years, both the student and teacher programmes have flourished, with both groups leaving the programme very satisfied. While running separately, the programmes are not necessarily unrelated. “The student programmes are basically our lab to develop materials and workshop stuff that we can then run with the teachers and get them to run in their own classrooms”, Sullivan explains. He has found that it is often helpful for teachers to build on ideas in their own classroom once the idea has already been brought up somewhere like at Bridge21. “A teacher can simply walk into school and say ‘right, we’re doing things differently now’, and sometimes it works, and sometimes that’s harder to do, whereas if the kids come to Trinity for a few days and have a very enjoyable positive experience here, and we introduce these kind of techniques and ideas, when the teacher wants to introduce some of this into the classroom, they can start by saying ‘remember how much fun we had in Trinity? Well we’re going to do some of that today’, and that can make that easier for them.”

In this way, Bridge21’s approach relies on academia. Tangney describes his own area of interest as “how technology helps the learning process”. The work they were doing led Tangney to the realisation that “what was going on here was applicable to more contexts than just outreach, that it was quite a powerful model of technology and learning and could be applicable to the school context”. From there, the project started working with a handful of schools on a pilot basis and has since gone on to work with “around 20 schools and 1,000 teachers in the past couple of years and over 12,000 students across a range of subject areas”. The programme also runs a variety of other projects, including working with girls in single-sex schools to promote coding and a postgraduate certificate in 21st-century teaching and learning with the School of Education – a teachers training certificate based on the Bridge21 model. As Grace Lawlor, Programme Coordinator, notes to The University Times: “Everything we do we’re gathering data. There’s a huge body of research behind everything we do.”

You can do all the outreach stuff that you want to and the limit of that type of work is that you reach only a particular cohort of students but if you can influence teachers and schools, then you’re playing at a totally different level

For Tangney and the team, “systemic change” is needed. While working with students directly is certainly worthwhile, it’s working with schools and teachers that can affect lasting change in how we teach and learn in Ireland: “You can do all the outreach stuff that you want to, and the limit of that type of work is that you reach only a particular cohort of students. But if you can influence teachers and schools, then you’re playing at a totally different level. Now, it’s much harder, it’s much easier to deal with students than with schools, but I think if you want the big results that’s how you have to work.” Their model is centered around project and enquiry-based group learning “that it’s not the teacher at the top of the room telling them what to do”, with one of examples of how they use the system in their own facilities involve Barbie dolls and rubber bands: “The challenge is ‘we’re going to throw these dolls out of the top floor of the building’ and you have to work out beforehand, with maths, the optimum number of rubber bands to give the doll so that barbie doesn’t split her skull but has the most exhilarating ride.”

Tangney adds his belief that the model could work in third level. He bases his first-year computer science classes on the model’s philosophy. Both Tangney and Lawlor note that technology should not be a substitute for existing modes of learning, but it should actively change how we learn. As Lawlor states: “The key is: what’s the technology letting you do that you couldn’t do before?”.

When students who have already been involved in Bridge21 programmes return, they develop a prototype and pitch the idea in a mini Dragon’s Den session. In doing this they work closely with Dr Jake Byrne, the programme’s computer science and STEM Programme Manager, who notes to The University Times: “I normally work with teachers, but this gives me an opportunity be a bit more creative and problem solve.” Some of the projects imagined by students in June included the “personal trainer”, which is “a shoe that basically detects how often you’re stepping, and if you drop below a certain level it speaks, and it goes ‘you could try harder'” and “the crone”, a drone disguised as a crow.

Bridge21 isn’t specific in what it teaches. Its main concern is in how things are taught. According to Sullivan, quite often it’s the teachers who decide what they want to do on a given week. Other times visiting teachers have more of an input. “Sometimes a teacher comes along and asks can we look at a certain topic, and we will, but more often than not we say that we want to do something with English and develop some activities around that, so we build a week-long programme and offer it to our partner schools, they jump on it, and we go from there.”

It is important for the programme that there is some overlap between the curricula at school and the alternative teaching methods so that everything feels new and interesting but also worthwhile

Last week, Bridge21 ran a Shakespeare programme with PhD candidate Sharon Kearney. Kearney finds that the students respond very well to the Bridge21 model: “Basically we’re trying to learn a Shakespearean play and about William Shakespeare himself through the Bridge21 model. We’ve taken the whole week, and each day we focus on a different style of language which is a critical part of the Leaving Cert curriculum too, so we look at the five styles of language and see how they applied to Shakespeare and then take on the Bridge21 model and pull all of that together”, she says to The University Times. It is important for the programme that there is some overlap between the curricula at school and the alternative teaching methods so that everything feels new and interesting but also worthwhile.

The response from students is overwhelmingly positive, with most of them saying they would like to continue the interactive and proactive learning experience in their schools. “It’s not like they sit you down at a desk, and you’re forced to learn”, said one transition year student attending the Shakespeare course to The University Times. “They teach you useful things, like how to make a video, how to edit, how to find good, reliable websites and spot the not reliable ones, while also teaching you about plays and Shakespeare.” The type of learning experience they have at Bridge21 is just what some students need, he says: “Not only did we learn about English here, we’re learning life lessons.”