Depending on who you are, what comes to mind when you think of the words “library” and “Trinity” might vary. For students, the library means studying, hiding cups of coffee under your coat and praying that the person beside you hasn’t noticed that you’re watching old episodes of Great British Bake Off instead of reading that tome of a text beside you.

For tourists and anyone who hasn’t witnessed the glory that is the Ussher Library at 10pm, their immediate thought would probably be the Long Room, the main room of the Old Library, famed for its dark, wooden interior and high, barrel-vaulted ceiling. The Long Room holds 200,000 of Trinity’s oldest books and is arguably one of the most impressive libraries in the world. It’s often found at the top of “Most Beautiful Libraries in the World” listicles, and for anyone who has made the time to see it (all Trinity students have free access to the library), they will agree that it’s a worthy accolade.

The size of Trinity’s library collection or its majesty is not the only impressive thing about it. Trinity’s main reputation for being a tourist hotspot in Dublin is largely down to the Book of Kells, which is on permanent display in the Old Library. The manuscript is famed for its age (historians have approximately dated it to the eighth century), its exquisite and intricate illustrations and how carefully it has been preserved by its curators. Having such an incredible artefact in its possession, it would be easy to presume that this is all Trinity’s library has to offer in terms of historical objects of note. If one was to delve further between the bookshelves, however, nestled away at the far end of the Long Room is the Manuscripts and Research Archive Library. Here, an extraordinary array of collections of items of interest that Trinity’s library has accumulated over the years is catalogued and maintained.

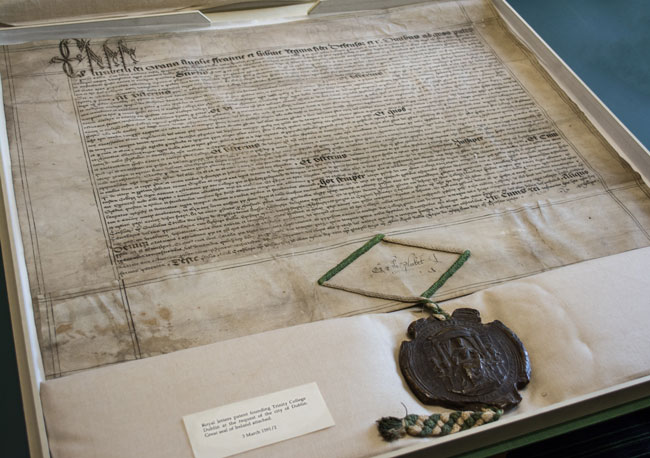

There are, in fact, over 20,000 collections housed in the Manuscripts and Archives Research Library. Starting when Trinity was founded, the library has been collecting items for 400 years. Until the establishment of the National Museum of Ireland in 1877, Trinity was one of the main institutions that acted as repositories for museum materials in Ireland. Speaking to The University Times, Estelle Gittens, an archivist in the Manuscripts and Archives Research Library, muses that items have “gravitated toward” Trinity on account of it being a mix of a library and museum. In 1894, College Board agreed to transfer many of their historical objects to the National Museum of Ireland. Although, with such an exhaustive collection, this was a barely noticeable loss to the departments catalogues and only certain items that “made sense” to move left. One of the collections that they donated was South Sea Island collection, which consisted of artifacts from the Fiji island such as “cannibal forks” used by chieftains at cannibal feasts.

A collection in the library can be one sole fragment of papyri, “written in Greek, excavated in Egypt” or 400 boxes of Victorian state papers that documented the Irish Famine

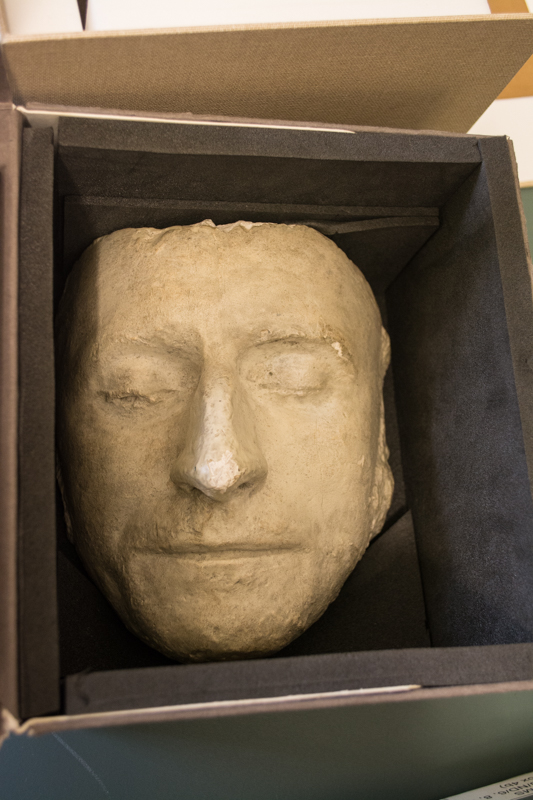

The library’s collection could only be described as unique and varied, ranging from items like the death masks of Wolfe Tone and Edmund Burke to 2,000 year old ancient Egyptian statues. The collection is awe-inspiring in the sheer amount of time it spans. As Gittens notes, the collection moves from “Babylonian cuneiform tablets, from the dawn of writing, right the way up to the university records created on computers today”. She elaborates: “Our collection is very old and spans all of those eras, languages and medium.” A collection in the library can be one sole fragment of papyri, “written in Greek, excavated in Egypt” or 400 boxes of Victorian state papers that documented the Irish Famine. It is truly a rich resource for any researcher.

Speaking to The University Times, Greg Sheaff, an assistant librarian in the college, notes that whilst the department may seem hidden away and virtually unknown by the student body, outside the walls of Trinity, it is “very well-known” to researchers and academics both locally and internationally. Gittens quips that the department is “hidden, but helpful”. Although items have to be maintained and preserved in very carefully controlled environments (the locations of which they refused to reveal), access to the collection is possible, and items can be requested for viewing, however as Gittens emphasises, this is solely for research purposes, and one must be a “bona fide researcher” if you want access to an item, be it for academic reasons or perhaps tracing your personal genealogy. This strictness may come from the fact the department has received obscure requests in the past, such as people wanting to see what medieval manuscripts “smell like”. Most requests tend to be genuine, however, and the department generally receives more emails than the duty librarian in the Berkeley/Lecky/Ussher (BLU) libraries.

Many fascinating researchers have graced the department, and the department would love to see how manuscripts are being used. It is difficult to keep track of what the collection has contributed to individuals research, as it not simply the case that they are being used for printed publications, which can be cited back to the library. In fact the use of the collection is highly varied. Gittens notes that she is currently in correspondence with a professor in Pennsylvania who requested the exact measurements of 17th-century manuscripts so that his class could produce books as they would have been printed in the 17th century. Often times schools in Trinity itself such as the Art History department request items so that students can study and examine them in class. It is truly an accessible and extensive resource for researcher, who simply has to make their way to the library website and put in a request through the manuscripts and archives webpage.

While the department’s collections could “never” compete with collections in places such as the Chester Beatty Library, it is still a large and significant collection with an abundance of unusual and unique objects

This is not the only way to access the collections, however. The department is keen for the public to have access to the collections, but space is a large obstacle in this aim. As Gittens explains, the department used to display items in the Long Room more prominently. However, the sheer volume of tourists and visitors in the room every day has made this infeasible. Instead, there are rotating, temporary exhibitions dotted around the Long Room, often in conjunction with College departments. This was the case with Upon the Wild Waves: A Journey through Myth in Children’s Books exhibition, which was curated by Dr Pádraic Whyte from the School of English. There are many digital exhibitions as well, such as the 1916 exhibition, Changed Utterly – Ireland and the Easter Rising, which explores 1916 from a range of political viewpoints. Gittens explains that this was to try and slightly remove the idea of Trinity as an institution being overtly “British” in that period of time and opened up a lot of researchers eyes to Trinity as a hub of centenary research, as opposed to the more traditionally thought of National Library or University College Dublin (UCD).

Gittens notes that while the department’s collections could “never” compete with collections in places such as the Chester Beatty Library, it is still a large and significant collection with an abundance of unusual and unique objects. For Gittens, she personally finds “the small, intimate kind of objects so much more fascinating”, items such as “diaries written by women, recipes” and other intimate, personal items that Sheaff explains have a “social history” element to them. There are items available for any niche researcher to get their inquisitive hands on.

There is no real “mystery” to the department, despite it being hidden away behind the heavy wooden walls of the Long Room. But what is there is a true historical depth and a vast array of incredible items that neatly span almost the entirety of humanity as we know it, items which are carefully and lovingly cared for by a passionate team of archivists. It stands as a testimony to Trinity as an institution dedicated to research and dedicated to knowledge.