What links ancient Egyptians, Tang Dynasty soldiers in China, Vikings in early medieval Europe, the Mohave people of North America and Gortletteragh Ballygar? Yes, obviously it’s that they all enjoyed a good tug of war, because the headline and the accompanying photo gave that away almost immediately. The latter team is the more recent member of this ancient tradition, an affiliated member of the Irish Tug of War Association (ITOWA) that recently secured a podium finish at the World Championships in Sweden this September. The club is based out of Galway, but the ITOWA is an expansive umbrella organisation that spans the country. If you’re a tad disoriented, I make no apologies for employing the classic rhetorical question opener to rope you into a novel subject matter. And I make no apologies for that pun either, nor any subsequent efforts.

Now, an anthropologist could probably make a very compelling case as to how those disparate groups of people are in fact linked by something far more complicated than their common contests of strength. But I think that on a fundamental level there is something very appealing about the idea of a tug of war in our political age. I chose those examples at random because, everywhere you look, there is a local variation on the traditional sport and a story to go with it. The official version of tug of war, as we would recognise it from sports days and the like, was born out of a maritime heritage. With nothing but rope and space on deck, crewmen and marines had to devise a way to keep fit during long voyages at sea. British officers observed their efforts while en route to India and staged the first competitions among their men upon disembarking, to the specifications we follow today. That being said, the human capacity for improvisation is limitless and local variations flourish all over the world, from just two competitors going head to head to massive thousand-strong showdowns.

Just this year in June, the residents of Estonia’s two biggest islands attempted to settle their age-old rivalry by staging their first ever tug of war using a 10-kilometre-long rope across the Baltic sea. The rope broke before either side could declare victory, which, when viewed from a poetic standpoint, could suggest the futility of adversarial approaches to geopolitical relations. From a practical standpoint, it suggests they needed a stronger rope.

Seeing political undertones where there aren’t any is my problem, though, and it has been a traumatic few months in that respect. At a time when the world seems to be pulling itself apart, I can’t help but apply the phrase “tug of war” to all sorts of probably inappropriate situations. Republican or Democrat. Remainiac or Brexidiot. Even its various definitions sound like vaguely Marxist notions of class conflict: “The real struggle or tussle, a severe contest for supremacy.” The aforementioned Mohave people even used tug of war as a mechanism for conflict resolution, and I have to admire their literal interpretation of hands-on democracy.

Just this year in June, the residents of Estonia’s two biggest islands attempted to settle their age-old rivalry by staging their first ever tug of war using a 10-kilometre-long rope across the Baltic sea.

So, it might surprise you to know that aside from serving as a metaphor for politics, tug of war is a thriving sport in Ireland, and our men’s teams regularly finish in the top three on the international stage. In fact, Gortletteragh Ballygar’s 640kg team finished third at this year’s World Championships in September and, as a result, they’ve qualified to take part in the World Games in Wrocław next year. This success is down to the tireless work of the Irish Tug of War Association, the amateur organisation responsible for governing the sport of tug of war here in the Republic of Ireland. After all of my research, it was a relief to talk to the President of the association, Daniel McCarthy, and the Ladies Liaison Officer, Cathy O’Toole, about their love for the sport.

McCarthy, as president for the last six years, has been involved in the association in some capacity since 1983. When asked whether I could record our conversation over the phone, he laughed: “Once you don’t take me to court I don’t mind.” After I assured him no court cases were likely to ensue, he told me about the origins of ITOWA, which is celebrating its 50th anniversary next year. The association held its very first meeting in 1967 in James Gate Brewery, as Guinness were providing most of the sponsorship, and the very first National Championships took place later that year in the Iveagh Grounds. In the decades since, the association has developed steadily, something which McCarthy is incredibly proud of: “Currently we have 55 clubs in the association and over the past number of years it has changed a lot because up to recently we had only men’s teams, but in the last 12 years we’ve introduced ladies teams and youth teams. It is a great expansion to have.”

Ireland is very much at the forefront of tug of war in Europe and will be heavily involved in hosting competitions over the next few years. McCarthy explains how we play a crucial role in facilitating the sport: “We actually are holding the 2019 European Outdoor Championships here, in September, and the following year, in February 2020, we are holding the World Indoor Championships.”

It’s a little bit more difficult to keep them in tow because you know they have so many distractions today. It is a big task for us to keep them involved. They’re looking for a reward for their efforts and, unfortunately, there is no financial gain.

Always with one eye on the horizon, McCarthy frequently refers to the youth teams as the future of tug of war in Ireland and places great emphasis on getting young people involved as much as possible, quite rightly in my view. However, his prescience doesn’t end there, and he expresses a concern that resonated with me, echoing the way many people view our millennial generation: “It’s a little bit more difficult to keep them in tow because you know they have so many distractions today. It is a big task for us to keep them involved. They’re looking for a reward for their efforts and, unfortunately, there is no financial gain.”

When young people are still in school with each other, they can go along to competitions together and bond as a team. When they turn 18 and head off to work or to college, however, they tend to lose touch with their teammates and drift out of the action. Of course, that’s just a natural consequence of growing up, but it’s hard to not feel a bit wistful listening to McCarthy describe that long goodbye.

O’Toole, on top of her role as Ladies Liaison Officer, is also promoting the sport in schools on behalf of the association, a task that is among the association’s top priorities. Over the European Week in September, she organised a tug of war event at the Garda Headquarters for people of all ages, backgrounds and fitness levels. She was very helpful in explaining the nuances of competitive tug of war to me, a novice. Certainly, there’s a lot more to it than you might think. For starters, there are actually two different competitions, outdoor and indoor, with slightly different skills involved. The outdoor season runs from June to August, while the indoor season runs throughout the winter.

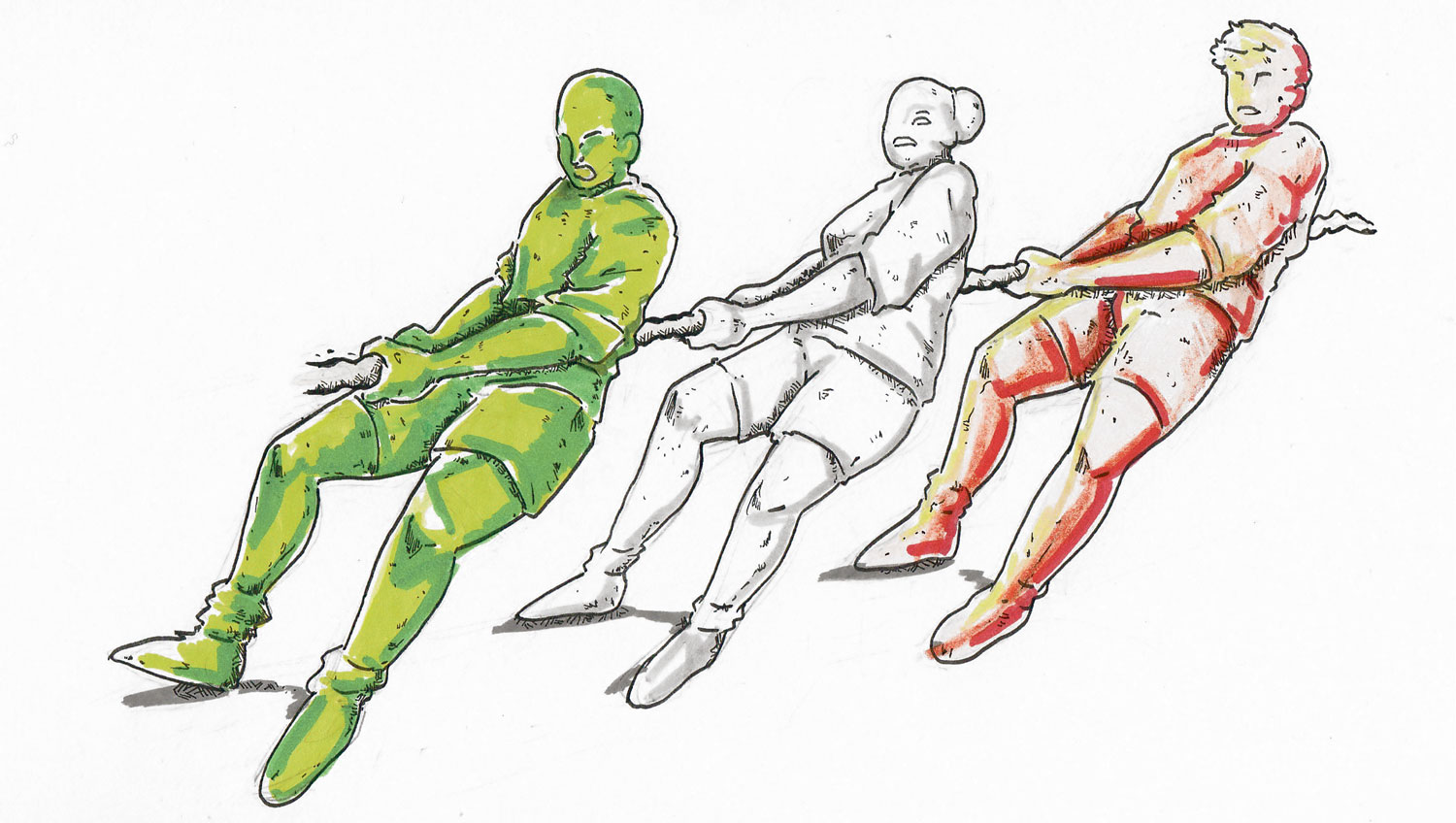

Each competition has its own adaptations that teams can make use of. Indoor teams pull on a special rubber mat with rubber-soled shoes, while outdoor teams use a “form of modified ski boot made of hard plastic with a steel toe” so that they can dig in for grip. Other technical additions abound: “The jersey that we wear has padding down your right hand side to protect the rib cage, so you’re not getting any rope burn, and then we’d use a resin on our hands for grip. Makes them last a bit longer.” It’s become far more sophisticated than the informal contests I took part in on school sports days, and O’Toole very much focused on how to maximise competitive advantage. A number of different tactics can be employed by the wiley tug of war team to tire out their opponents and gain that decisive edge. Several different guides are available online, and I include below a collection of my personal favourite ploys.

Firstly, teams try to pull in a concerted rhythm, as dictated by the team captain. This guarantees that all of their efforts are concentrated into each pull, which weakens opponents until they can be reeled in. Secondly, when the opposition are pulling, a team can brace against each heave by lying back into the rope and literally digging their heels in, until their opponents exhaust themselves. Finally, the most devious tactic is the false pull, whereby a team exaggerates their efforts in order to encourage the other side to brace. Then they feign exhaustion, to act as bait. When their opponents rise for an easy victory, the trap is sprung. Sun Tzu would be proud of the deception, as would any other military strategist.

However, allow me to strike a note of caution. You should never, that is, NEVER, wrap the rope around your wrist, your arm or your hand. In fact never wrap it around any body part. The rope will cut off your blood circulation. Worse than that, I came across too many stories of fingers, hands or in one extreme case an arm, being amputated when ropes that weren’t fit for purpose snapped.

Moving swiftly onwards, one feature of the association which makes it distinct from other amateur sporting organisations on this island, such as the Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA), is how well it balances the parochial with the international. On the one hand is Letterfrack, Letterkenny, Clonakilty and Dunshaughlin. Four towns from four provinces, each with its own affiliated club, each run by local volunteer members. On the other hand, teams regularly travel to European and International Championships to represent Ireland, and McCarthy has recently returned from a three-week coaching trip to China: “China is a dominant force, as everybody knows, in every aspect of the world. The ladies team from Chinese Taipei are the World Indoor Champions. Up to recently they didn’t try a lot of outdoor tug of war but they can see the prospect of gaining status in the outdoor season as well.” Despite their might, he recalls how the ladies team came to him for guidance: “They invited me over to give them training and emphasise the aspects of outdoor performance that will make them better. If you go to Hong Kong, Macau, Bangkok, Singapore, Malaysia, they all have tug of war teams now.”

We now have visually impaired people involved in Tug of War, because [O’Toole] is very interested in that aspect also. It just goes to show how open Tug of War is to everybody, it is a great day out for them, to feel part of a team. The disability doesn’t come into it.

Speaking of Singapore, McCarthy will be heading over there in February to provide them with his expertise and assist them, much as he did the Chinese teams. Always one to look outwards for opportunities, McCarthy’s international vision is very refreshing at a time of increasing xenophobia and isolationism. However, talking about tug of war specifically, he and President elect-Trump can probably agree on one thing: “With the emphasis that China put on everything that they do, within the next few years they are going to be a very very strong country to contest with.” To counter such a formidable challenge, McCarthy has been looking to neighbouring associations for inspiration. Both the Swiss and the Swedish in particular have an excellent model for youth development, which the association are hoping to emulate: “What we need to develop is, from a very early age, a European standard of performance. Once you progress from the youths, we have underage teams, under 22 and under 23 teams.” This youth emphasis will feed competitors into the national set up and improve the retention of young athletes within the association and the sport.

ITOWA’s progressive attitude doesn’t just encompass an international outlook. It is also looking to pull down barriers to people with disability in sport. McCarthy’s sister, Dr Patricia McCarthy, is an Associate Researcher within the School of Education in Trinity and is looking to get visually impaired people into tug of war. “We now have visually impaired people involved in Tug of War, because [O’Toole] is very interested in that aspect also. It just goes to show how open Tug of War is to everybody, it is a great day out for them, to feel part of a team. The disability doesn’t come into it.”

Finally, I had to ask whether he harboured any aspirations to return the sport to the Olympic Games, seeing as it had been a track and field event from 1900 through to 1920, when it was dropped due to a lack of participating nations. With Irish teams performing so well at the highest level, any move to reintroduce tug of war to the games would give Irish athletes an excellent shot at an Olympic medal: “Of course, everybody’s dream is to represent their country at the Olympics. It would be a marvelous achievement if we could get it back into the Olympics. Now, we are trying very hard at present, but the Olympics feature sports which are very dominant and produce a lot of revenue. We’d be at the bottom of the list producing that kind of revenue. Golf is a new Olympic sport which produces huge revenue and everybody watches how spectacular it is on television.”

It would be a marvelous achievement if we could get it back into the Olympics. Now, we are trying very hard at present, but the Olympics feature sports which are very dominant and produce a lot of revenue. We’d be at the bottom of the list producing that kind of revenue.

“Our event would also be spectacular, if we could get in”, he adds with a laugh, not bitter at all.

On the contrary, I felt like the air had been let out of my balloon somewhat. Golfers have plenty of opportunities to excel on the world stage, and they dream of winning Masters, not Olympic medals. Considering many of the golfers clearly felt that the Rio Olympics just wasn’t worth their time (our own Rory McIlroy included), I do feel a little disappointed that these dedicated, amateur athletes were overlooked for purely capitalistic reasons. Now, of course many of the golfers who declined to attend cited the Zika virus as their reason for dropping out. Without casting any aspersions on the validity of that concern, I’d be very skeptical of their sincerity. Athletes from almost every other discipline assessed the risks involved and competed anyway, because for them the Olympic Games is the pinnacle of achievement in their field.

I’m reminded of Goldman’s dilemma. Robert Goldman, a renowned physician, asked elite athletes in his native Australia a simple question. Would they take a drug that would guarantee them overwhelming success in sport but cause them to die after five years? More than half of those he asked responded that they would. For golfers at Rio, the risks at stake were infinitesimally smaller, and yet few of the world’s elite seized the opportunity to represent their country. I know that a prospective tug of war team would not have a moments hesitation in those circumstances, their passion and dedication throwing the cynicism of top golfers into stark relief. I’ve harboured those qualms about golf in the Olympics ever since the decision was announced, and so I do hope McCarthy will forgive me for venting them now, as he was entirely gracious in his acceptance of financial realities.

Still though, as he reminds me in parting, tug of war is one of just three sports that is won going backwards. The Irish Tug of War Association will keep tugging until something gives.