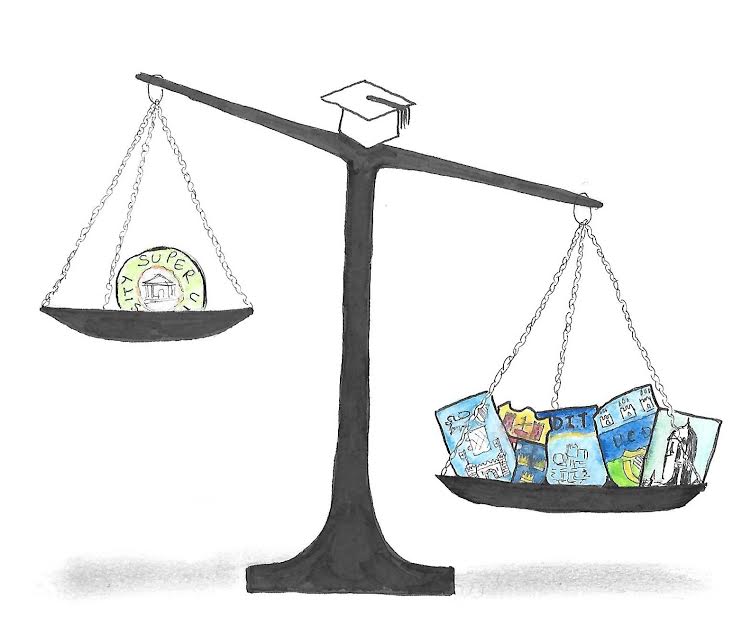

The idea of Ireland having a single “super university” has recently gained traction as a means to arrest Irish universities’ fall in world rankings and to generate internationally renowned research. Proponents suggest that Ireland cannot afford more than one top-class university, given our small population. To quote an article in the Irish Times: “It’s Hobson’s choice for Ireland: one outstanding institution of higher education and research on the world stage now, or none.”

This declaration is not only flawed by way of binary reductions, but there is also the fact that Irish universities presently produce research on the world stage. That fact is made clear by the admission of Trinity last month to the prestigious League of European Research Universities (Leru), in recognition of Trinity’s contribution to research. That truth aside, the idea that we can improve our position in the rankings by streamlining resources into one elite institution bears some credence. However, it is important to reflect on the consequences that this would have on education throughout the country.

The idea that we can improve our position in the rankings by streamlining resources into one elite institution bears some credence

It is argued that our population is too small to support several universities at a high level, drawing a comparison to larger countries, such as Germany and France, by calculating their number of universities per capita. However, the comparison between large and small countries is not so simple. Large countries, by virtue of their nature, benefit from having a litany of universities and the diversity that brings. Of course, small countries will have fewer universities than larger states, but there is a clear benefit to the diversity that is gained through having more than one such institution. Barring micro-states whose population is tiny, developed countries of several million people can afford to have more than one university operating at a high level. Indeed, our national market would be deprived of diversity by restricting ourselves to a single institution of higher learning.

A worrying consequence of having a single elite university is that it would pave the way for academic uniformity. Consider the role of the lecturer, which includes bringing their unique perspective and analysis to a field of study. Where there are more lecturers with their diverse perspectives, this creates a more rounded education for students. Looking beyond the sheer number of lecturers, it is also true that university departments and schools are subject to academic governance, which influences the content of modules.

Students of the Trinity for Economic Pluralism group provided an example of the risk of academic uniformity in a department. This group of economics students campaigned against the dominance of the Neoclassical school of economic theory that is so prevalent in the department’s modules. Unless we are ardent ideologues, we should accept that any school of thought has its weaknesses, and so a diverse scope of content combats the formation of single-minded attitudes. However, if we have a single elite institution, its content would also be influenced by academic governance.

When we consider that the function of an elite university is to develop the future decision-makers that run our economy, there is an alarming risk of academic uniformity, which would develop students with blinkered attitudes. As a country, that risk is mitigated by having several universities, from which we develop a broad pool of students with different training and experiences.

Notwithstanding the concern for academic uniformity, a single elite university located in Dublin would exacerbate the regional disparity in Irish education. The reality of an elite institution would also establish a three-tiered system of education, by creating a distinction between it and regular universities, as well as institutes of technology (ITs). The findings of the Hunt Report, part of the government’s National Strategy for Higher Education, were opposed to that divergence. It suggested the retention of current universities and merging several ITs to create new technological universities. Rather than creating a three-way split, this proposal would maintain the current universities and strengthen ITs, which would ensure a regional balance in education.

While Dublin’s economy is advanced, the city’s resources are under immense strain as its population swells. The housing crisis is a flagrant example of this, as the supply of housing fails to meet demand and prices skyrocket. Rather than the government focusing solely on Dublin by developing an elite university, investment in University College Cork (UCC) and National University of Ireland Galway (NUIG) will make them more attractive options to future students. This would ease the strain on Dublin and balance out the standard of education across the country, benefitting rural students for whom moving to Dublin to study has become increasingly unaffordable.

As that funding shortfall is yet to be restored, therein lies an obvious remedy to the fall in rankings

Having just one university, too, runs the risk of such an institution becoming complacent. After all, when you’re the only university in a country, you’re always going to be the top university in that country. As Provost Patrick Prendergast noted in his address marking the midpoint of his 10-year tenure, University College Dublin (UCD), launched a €65 million bid in October to become one of the world’s top 50 business schools within the next five years, an announcement that came after Trinity’s plans for a new €80 million business school. “Who believes UCD would have invested in the Smurfit school if we hadn’t invested in business?”, Prendergast asked the crowd. ““A successful city needs two.”

Looking to the rankings, it must be noted that Irish universities’ fall in world rankings has been preceded by a dramatic fall in state funding. As that funding shortfall is yet to be restored, therein lies an obvious remedy to the fall in rankings. Whether or not funding will be restored depends on which of the three options the government chooses to pursue from the Cassells Report. However, a full restoration of previous funding is unlikely. In that case, research can be improved through more collaboration between universities’ respective departments. This would reduce the cost of output and allow for a broad perspective, while maintaining their mutual independence. Students pay the same student contribution charge at all of our universities and institutes of technologies, it would be unjust to create an elite university that takes away from our other institutions.

And besides, former head of the Higher Education Authority (HEA) Tom Boland, speaking at the third annual “Leaders in Higher Education Address” organised by the Royal Irish Academy in March, called the argument that we should put money into one world-class institution “nonsense”, adding that even if we did combine all of our money, it would still not be enough to create a top 10 university.