Prof Peter Hunt’s last interview with The University Times – or the University Record, as it was then known – was way back in 2004. Yet, it seems that many of his gripes with the intellectual perception of children’s literature persist. Without institutions like Trinity offering higher-level courses in the subject, it would still be confined to the status of “the weird sister” of English departments. Supposedly the first PhD in the area, Hunt’s work set a precedent for children’s literature as a serious academic pursuit. Without his input the Trinity course would probably not have come about.

After 40 years in the field, Hunt finds himself dispirited by children’s literature’s persistent reputation as whimsical and sweet. He has campaigned tirelessly to dispel this myth, and while progress has been slow, it is progress nonetheless. Perhaps people find the subject simplistic because virtually everyone has read a children’s book. So, by default, everyone is a seasoned expert. Hunt affirms this, also recalling a “frightening” experience with the Arthur Ransome Society, who did not take kindly to an expert turning up and telling them how to critically engage with Swallows and Amazons. Seemingly, responses to Hunt’s work range from simpering to frosty, despite his having delivered lectures across the world. Trinity is one place in which it seems his views are always welcomed.

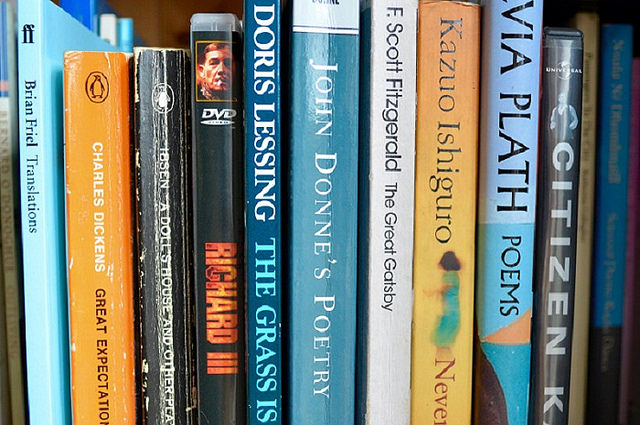

In 2015 in the UK, children’s books outsold adult books for the first time. In 2016, book sales were up 20 per cent in Ireland overall, with children’s books sales up by 24.4 per cent – a €26.7 million market. You only need look at the window display of Trinity’s neighbouring bookshop, Hodges Figgis, to see the evidence of this upward trend. While these figures are encouraging for us, the enthusiasts, the market does not comprise entirely of good-quality children’s books. I ask Hunt for his stance on the rising trend amongst celebrities who turn their hand to writing kids’ books. His expression gives him away. As an author, he finds it unfair that being famous for something else gives you automatic status in the literary world. As a critic, he finds it frustrating, as most celebrity literature is “pretty awful”. On the whole, it is a double-edged sword, as while it raises the profile of children’s literature and sustains the market, it simultaneously perpetuates the idea that anyone can write the stuff. Suffice to say, these kinds of books are not allowed in the Hunt household, or on Trinity’s M Phil in cildren’s literature. As is to be expected, the reading list stays away from celebrity books. In fact, it’s more likely that you will have to read something which is squirreled away in Early Printed Books, than go and find Madonna’s latest kid’s book.

If you go through the history of a period, they often just completely blank children’s books

My next question for Hunt lies with the other side of children’s literature: the critics. In his 2004 article in the University Record, Hunt commented on how many other critics, amidst their own complaints about being marginalised, simultaneously forgot – wilfully or otherwise – that children’s literature existed. Rather than form a united front, the fields of marginalised critics and writers was somewhat splintered. While things are somewhat better now, speaking to The University Times, Hunt remains sceptical: “I still suspect that if you look through a biography of any major author who may have written children’s books, you won’t find it mentioned at all”, and “if you go through the history of a period, they often just completely blank children’s books”. Even biographers who claim to be holistic, it seems, fail in their broad-minded pursuits because of these omissions. This is despite the fact children’s books and their cultural impact offer a wealth of information and new ideas to historians, cultural theorists and fiction writers alike. The responsibility lies with the likes of Dr Pádraic Whyte, Dr Jane Carroll, Dr Amanda Piesse and a wealth of others here in Trinity who stand in children’s literature’s corner.

“Progress”, Hunt reiterates, “is painfully slow”, as things in the field seem to rock back and forwards. He does, however, note how much better off we are in this part of the world than elsewhere, citing France and Italy as relatively underdeveloped in their approach to an understanding of the field. This is made evident by the clutch of writers studied on the M Phil, comprising mostly UK, Irish, US and Scandinavian authors and critics. I ask if he thinks that, on the whole, there is now more intersectionality between children’s literature and the underrepresented critics of the University Record days. While there are still some “dinosaurs” – which is of course true in almost every field – he says that “marginal subjects have been accepted into the general matrix”, children’s literature included.

The acceptance of creative writing into the academic setting has involuntarily helped the cause of children’s literature. Once something as subjective as this became commonplace in universities, it was hard for the “old-school academics” to be prescriptive or standoffish about children’s literature. Admittedly, it did take some time before the two coexisted at Trinity – about 12 years – but now many lectures and symposiums are open across the M Phil courses: children’s literature has made a place for itself. Given the rise of specific creative writing and literature courses, I ask Hunt whether he can foresee the creation of more specialist children’s literature degrees, such as a Young Adult fiction course. While they may be a long time coming, he believes this could be possible, so long as the upward trajectory continues as it has throughout his career. He cites resources such as the 40,000-book Pollard Collection in Trinity as vital to the continuation of cutting-edge and interdisciplinary research. It is resources such as this which make it such an enticing degree, as well as certainly giving weight to its academic credentials.

If children’s literature were to be proffered as a more serious topic, perhaps as a Leaving Certificate or A-level subject, then with any luck the field would attract a more diverse range of students and prospective researchers

Hunt’s University Record piece also outlined six reasons why children’s literature needs to fight prejudices. One such prejudice was that it is a female-dominated field. I ask him what he makes of the current Trinity M Phil intake comprising of 18 women. He responds by interrogating me. Do I think, despite the evidence to support it, that such a gender-heavy view is still valid? Given that females make up the majority of literature degrees in general, including undergraduate English in Trinity, it is not all that surprising. With this in mind, it is ironic – though not surprising – that so many of the revered names in the critical field are male. Of course, there are a litany of cultural factors that allow this stereotype to persist: women are deemed more nurturing and therefore more likely to have an intrinsic understanding of the subject, girls are more likely to read at a young age than boys and females are supposedly more conscientious on the whole … the list goes on. To change these imbalances, change needs to be instigated from a lower level. If children’s literature were to be proffered as a more serious topic, perhaps as a Leaving Certificate or A-level subject, then with any luck the field would attract a more diverse range of students and prospective researchers. He tells me later of his four grandchildren, two boys and two girls, and how their tastes are far from gender-defined. Instead, they are totally character-driven. It is this view that needs to be seized upon across multiple fields so that children’s literature is seen as more accessible to all. A good place to start would be attempting to really sell the subject to Trinity undergraduates taking the children’s literature module.

As we finish up, Hunt comments on how fascinating it is that our conversation has covered a breadth of issues. I feel this to be testament to the multi-faceted nature of the subject as a whole. While I am not denying that it has its sweet moments, it tackles much larger issues head on, both in the fiction that goes under the microscope, and the criticism that is produced as a result. Places like Trinity are helping to dispel the myth that children’s literature is so much more than just “cute”.