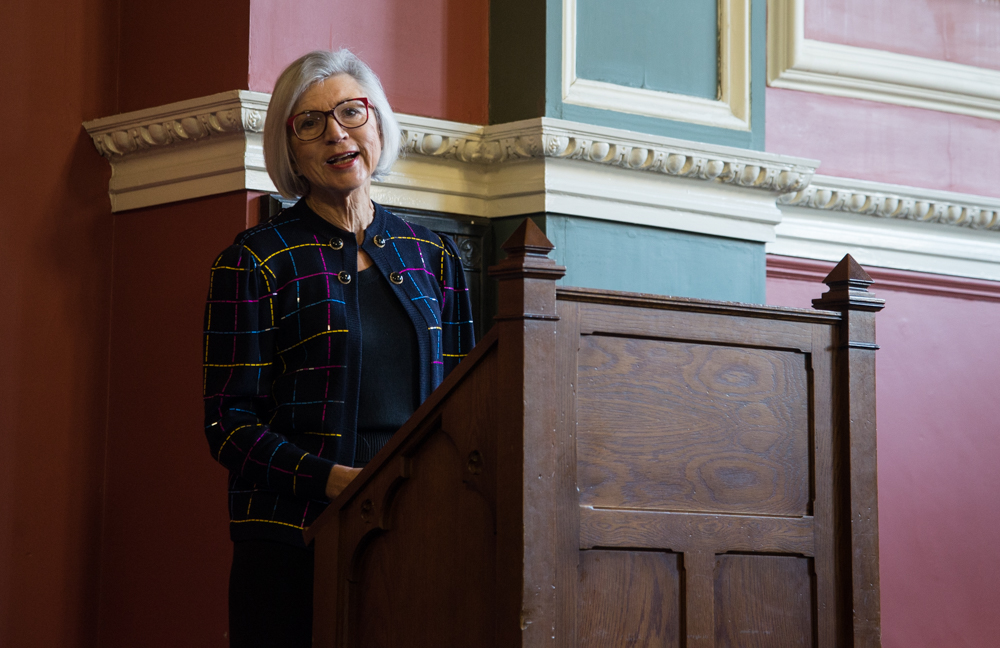

The Right Honorable Beverley McLachlin, Chief Justice of the Canadian Supreme Court, addressed Trinity Law Society (Law Soc) in the final event of their speaker series for 2016/17.

Accepting the Praeses Elit award from Law Soc for excelling in her profession, McLachlin said it was “a great honour” to receive the award, particularly given her admiration for former Irish President and Law Soc Auditor Mary Robinson.

Opening her address in the Graduates’ Memorial Building (GMB) with a run-down of the strong ties between Canada and Ireland, McLachlin pointed to the hundred of thousands of Irish emigrants who have sought a new life in Canada throughout the years, citing the fact that 15 per cent of Canadians claim Irish heritage today and that the two countries “remain firm friends” through shared values such as diversity and respect for the rule of law.

McLachlin then spoke from her own expertise and experience on her view of judicial accountability and independence, stating that it is “no surprise to say that we live in an age of transparency and accountability”. Canada’s longest serving Chief Justice spoke of a “certain pessimism” throughout our society about our common future and a perception that “democracy is under siege”. McLachlin alluded to an attitude among members of the press that the judiciary, as it is not directly accountable to legislatures and executives, is not responsible to the people and has “illegitimate” power, before countering this argument with her own comprehensive list as to why, in her opinion, that is not the case.

Declaring that, ultimately, the judiciary “should be responsible for and responsive to the people”, McLachlin went on to say that judges are accountable “indirectly” through various means, such as the right to appeal decisions, their own “reasons” for making any decisions which are a matter of public record and principles of judicial conduct which are observed by and enforced by the judiciaries of many countries, including Ireland and Canada.

McLachlin also touched briefly upon the open-court principle and that “justice must be done and be seen to be done and cannot be seen to be done behind closed doors”, as well as mentioning a story of how she encountered a friend outside a courthouse who was incredulous as to the fact that they could go inside and watch justice play out: “Do you mean I can go in there?!”

McLachlin continued to push-home her argument in a way that only judges seem capable of, building on these points by referring to a number of ways that contemporary judges and judicial systems have made accountability to the public a priority, specifically providing information to journalists to aid their reporting of cases, making judgments available online and live-streaming cases.

“Accountability is not the enemy of judicial independence, but rather its natural partner”, McLachlin added.

Rounding-off her address with a welcomed “go raibh maith agat”, McLachlin then began to take questions, first from host and Law Soc Auditor Hilary Hogan, before opening up to the crowd.

Hogan’s first question for the Chief Justice happily tied-in with her “favourite day of the year”, International Women’s Day, as McLachlin was asked what she felt had changed for women in her profession since she had started practicing law. McLachlin spoke of a “very different time” when she qualified as a lawyer in 1969, reciting a story of applying for a job in a law firm as a married woman and being asked “why do you want to work?”

McLachlin also talked about an atmosphere of “heightened sexual and gender scrutiny”, including “off-colour” jokes made in front of women and regular cat-calling. “As a woman, you were constantly feeling that you were not just a lawyer, but a lawyer who was also some sort of sexual object”, she reflected.

To overcome these difficulties and achieve a sense of “serenity”, McLachlin said that she woke up one day, said to herself “I am a woman” and that “if they wanted to say sexist things, that was their problem, not my problem”. McLachlin pressed home this idea of “staying true to yourself” in the midst of seeing ourselves in the eyes of others, particularly for women, which McLachlin said can have a “paralysing impact”.

Interestingly, on the topic of constitutional change through public referendums – the only avenue for such change in Ireland – McLachlin voiced her concern over how referendums amount to “snapshots” in specific times of public sentiment and critical matters being decided “on a single vote”.

While not wishing to criticise countries that conduct referendums regularly on constitutional matters, McLachlin the need for a “clear majority on a clear decision” to decide such issues, citing the example of the 1995 referendum on Quebec sovereignty, a complex issue which “nearly tore our country apart”, with 49.42 per cent in favour of seceding.

McLachlin then went on to field questions regarding Canadian federalism, Quebec’s “distinct society” and factors apart from the law that influence judges. On this final question, McLachlin revealed that she tells herself that while she may have her own personal viewpoints, her job as a judge “is to have objectivity”. While acknowledging that people have differing religious and moral views, McLachlin said that she has to stand back and tell herself that judges must uphold “the law for everybody, not just those of my religion”.