Despite this week’s announcement that the government will allocate an additional €47.5 million to the higher education sector in 2018, the perennial issue of the need for a new and sustainable funding model for Irish universities has been kicked down the road to be dealt with at a later date yet again. This isn’t hugely surprising but it is disappointing for third-level institutions and students alike.

With huge problems affecting more emotive sectors, such as housing and health, the government is being allowed to sit on its hands as it awaits a report from the Oireachtas Education and Skills Committee outlining its preference for a particular funding model.

As has been reported on numerous occasions in these pages, yet worth remembering once more, the committee is likely to choose one of three models proposed by Peter Cassells in his expert report published in July 2016: a predominantly state-funded system that would see an end to the student contribution charge, a continuation of the current system coupled with increased state investment or an income-contingent loan scheme that would see students pay for their education only after they’ve reached a certain income threshold.

Since student fees along with generous state loans were introduced in the UK 20 years ago, the number of poorer students attending university has increased and continues to do so

Student groups such as Trinity College Dublin Students’ Union (TCDSU) and the Union of Students in Ireland (USI) have not been shy about what system they want: the so-called “free fees” option funded through general taxation.

Last October, after USI’s March for Education, I argued that a publicly funded model was an unrealistic ambition in the current financial climate. I settled, somewhat reluctantly, on advocating for a continuation of the modest student contribution charge.

Having closely followed the debate around student fees that flared up in the UK over the summer and having further researched the topic, I’ve concluded that a system whereby students make a reasonable contribution to their university tuition only when they earn over a certain amount is, indeed, the fairest and most sustainable as student numbers continue to increase year-on-year.

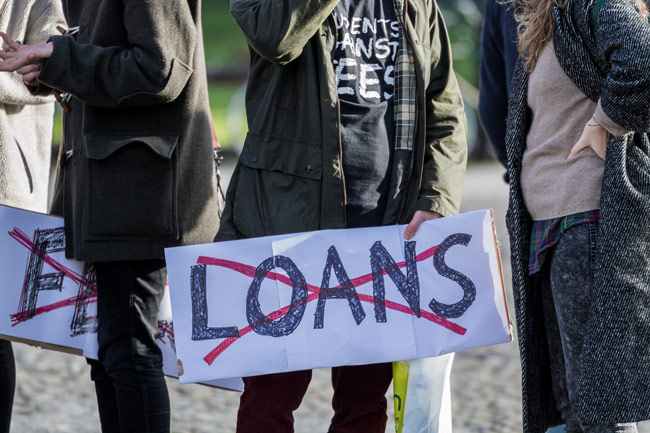

This is a view that is often met with derision, even hostility, from the above-mentioned student groups. This is because the narrative being promoted in this debate by the likes of TCDSU and USI is overly simplistic and polarised.

The income-contingent loan option is depicted as the evil of all evils within the student movement. It is portrayed as some sort of conservative coup within universities that would stop low-income families sending their children to third-level, when it is, in fact, a policy that has been implemented by centrist and even centre-left governments elsewhere. On the other hand, the model funded predominantly by the taxpayer – including many of those who will never attend university – is held up as a bastion of some warped view of equality.

Firstly, those who are opposed to a loan scheme often argue that such a system would limit access to third-level as graduating with a certain amount of debt would be too daunting for many students to deal with, particularly those from poorer backgrounds. This is untrue.

Since student fees along with generous state loans were introduced in the UK 20 years ago, the number of poorer students attending university has increased and continues to do so even with fees nearly trebling to £9,000 in 2012. By no means is the British system perfect – most universities charge the maximum fee and some student grants have recently been replaced by more loans for example, a regressive step – but there is no evidence to suggest that Irish students are more debt-averse than our British counterparts.

Secondly, those advocating for a publicly funded system like to make the point that third-level education is a “public good”. It is our universities that produce our doctors, teachers and nurses after all. This is true, but it is also the case that a university education is of disproportionate benefit to the individual who receives it, insofar as university graduates earn significantly more throughout their lives than non-graduates, as successive studies have shown.

This begs the question of who should fund third-level tuition. A publicly funded system would mean that all taxpayers would contribute to financing it, even those who never set foot in a university. This, to me, does not seem to be the shining light of progressiveness that some suggest it is. Considering those who complete a university education will, on average, receive a significant financial benefit from it, it does not seem unreasonable to suggest that students should have to foot a certain amount of the bill themselves.

Finally, the income-contingent aspect of the proposed loan system is often overlooked. It means that a student would not have to pay back a single cent until they earn above a certain annual threshold. In the UK, this has been set at £21,000 – soon to be raised to £25,000 – allowing students to manage their debt. Some estimates have put an Irish equivalent between €26,000 and €28,000 a year.

It should also be remembered that loans are already a reality for many Irish students. Incidentally, I took out my first loan in recent weeks to fund my final-year accommodation and have already started to pay it back. If there was a deferred payment system in place like the one suggested by Peter Cassells, however, I wouldn’t have to worry about any repayments until I was earning a reasonable salary.

A publicly funded system would mean that all taxpayers would contribute to financing it, even those who never set foot in a university

It is a regrettable situation that we find ourselves in. This debate has become so polarised as to become almost a treasonous offence for any prominent student politician to speak out against a “free fees” system.

In November 2015, for example, current TCDSU Education Officer Alice MacPherson gave a strong and convincing case against a motion to oppose a student loan scheme at TCDSU Council. When running for her current position, however, she backtracked and plainly said she “was wrong” for taking such a stance. MacPherson may have genuine reasons for changing her views on this issue. Regardless, it appears that it is unacceptable for any TCDSU sabbatical officer to go against the grain when it comes to student fees.

Our higher education system is of vital importance to our society and our economy. Therefore, the soon-to-be-taken decision on a new funding model is a significant one. Amidst the hysteria, students, politicians and other stakeholders should remember that an income-contingent loan scheme is a perfectly progressive option.