Yesterday afternoon, Fellows, Scholars, and the odd confused tourist gathered in Front Square to embark upon a tour of Trinity’s trees.

Led by Prof Daniel Kelly, the meditative walk around Trinity’s grounds offered a glimpse into the campus’s collection of over 600 trees. From New Square’s lumpy plane tree pair to the oriental offerings of the Rose Garden, College is a botanical melting pot, with many of the trees telling untold tales of Trinity’s past.

With trees so firmly rooted in both the real and imagined collective landscape of Trinity, tree removal on campus often provokes an emotive reaction from the College community. The news that Trinity would lose some of its beloved cherry trees back in 2016 had many reeling. To pre-empt this kind of outcry, Estates and Facilities often take to circulating carefully worded disclaimers by email, warning people well in advance of any trees getting the chop. Proper tree service removal stockton needs to be done with care to ensure nothing else is damaged and it is done in a safe manner so it could take some time to complete.

But it’s not the College’s fault that some trees have to be axed. Kelly somberly reminded tour participants: “Trees are not immortal.” In fact, the cycle of replantation on campus is in constant swing. Thanks to storms, disease, and issues with the soil, trees regularly have to be removed. This is not always an easy feat. But is something that must be done to help make sure that the healthy trees are safe – with the help of companies like this tree removal Jacksonville company we can get this all sorted easily. Recently, Trinity Security risked life and limb to deal with a dying tree at Lincoln Place gate.

Keeping trees alive is no walk in the park either. As can easily be observed, a lot of Trinity’s trees have cables in them. This is to help the trees survive the increased wind speed created by Trinity’s buildings. Cable bracing is a tense surgical procedure that involves drilling holes through the trees, with a window of less than a minute to get it right.

Front Square’s iconic oregon maples are one of many to receive this treatment. Located in front of the Rubrics, they stem from the Americas, having arrived as young trees back in the 1820s. Unfortunately, one of their sister trees was lost to a freak storm in 1948.

The square is also home to a Russian stone birch, a magnolia tree, two unusual Mongolian lime trees, and the slow-growing, oft-considered weedy, sycamore.

Lumbering on to New Square, Kelly showcased the Turkish hazel, a Japanese katsura, and a silver birch among others.

In front of the Museum Building lies a white mulberry tree, food of the silkworm. This tree is in fact the only kind of plant that this valuable worm can be fed on. Back in the days of James I, when England had lofty plans to be self-sufficient, they attempted to populate the country with these trees. Unfortunately for them, they accidentally planted the wrong kind of mulberry tree and instead ended up with the ingredients for a surplus of jam. “There’s a moral there”, said Kelly. “We need taxonomists.”

In the corner of New Square sits a couple of wizened plane trees, which Kelly calls the Darby and Joan of Trinity trees. These are two of the oldest trees on campus, dating back to about 1830.

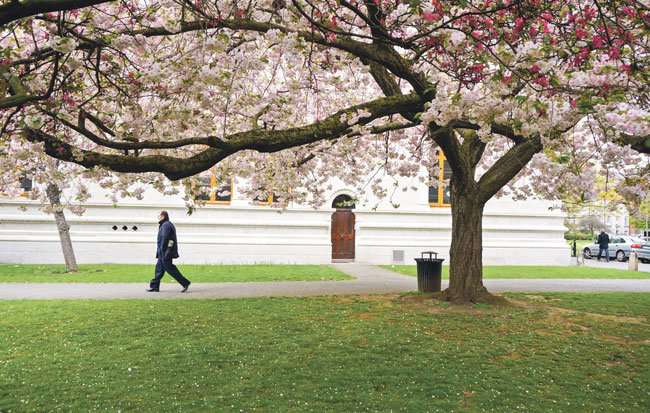

In terms of international diversity, Trinity’s Rose Garden branches out even beyond what New Square has to offer. While cherry blossom petals rained gently upon us, Kelly explained that most of the garden’s botanics hail from China and Japan.

The garden’s sweeping cherry blossom trees are what Kelly calls “hybrids of complex origin”. Kelly admits to being stumped by the mysterious lineage of some of Trinity’s trees. When it comes to the apple and cherry family, for example, it’s hard to determine these hybrid trees’ exact roots.

Lining the cricket pitch are, well, more trees. Trinity’s most diverse and impressive arboretum stretches from the bottom of the cricket pitch to the Chemistry and Zoology buildings, with trees from the evergreen oak to a rather happy-looking willow populating the way.

The triangle in College Park is home to several Hogwarts-esque sounding trees, including the snakebark maple, easily recognisable thanks to its scaly, striped trunk. It’s also a rich breeding ground for hornbeams, which are common all over Dublin, notably in the RDS and Herbert Park.

This spot also houses a Hungarian oak which, despite being what Kelly calls “a particularly splendid tree”, remains quite rare. This is due to its slippery leaves, which deters many tree growers from planting them in public places.

Then there’s the medlar, a curious plant that has been cultivated since Roman times, which produces fruit that’s just about edible if it’s beginning to rot. Unfortunately for the medlar, the taste for rotting fruit is not much in demand.

Kelly’s tour concluded on a bittersweet note about the uncertain future of some of Trinity’s tree species. Many are currently concerned about the common ash, which is at risk due to the spread of ash dieback disease.

Such fears aren’t unfounded, with Trinity’s tree population having been dealt several hard blows in recent years. College Park was once packed with elm trees. Today, there is only one elm tree left, with its last remaining fellow elm having died a few years ago. Originally this was thought to be the work of Dutch Elm disease, though no trace of the strain has actually been found in Trinity specimens.

Now Trinity’s botanists suspect that something in the soil is causing this nightmare for elm trees. As it stands, however, there is still hope for Trinity’s elm population, with the final elm tree still appearing healthy and in good spirits. Removing any trees need to be done safely and professionally, this is where companies like Rich’s Tree Service will be contacted to consult with.