It goes without saying that a university’s library is one of its most important institutions. Without a functioning library, the very idea of a university becomes untenable. From an academic standpoint at least, libraries are at the heart of what colleges do.

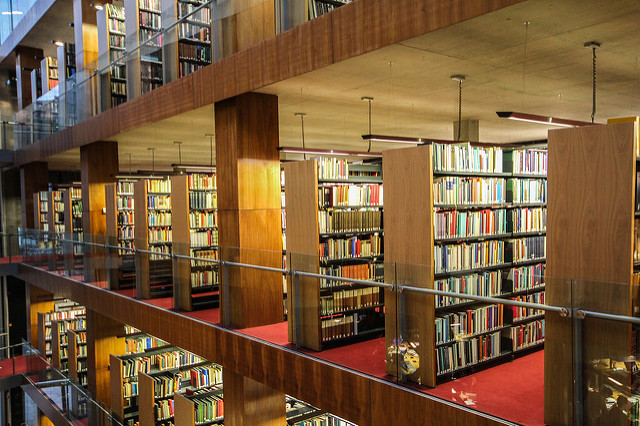

It’s lucky, then, that in Trinity, students are well served by the stacks. The various library buildings on campus are ideal places to study, and no one can deny the depth and breadth of the library’s collection. Trinity’s privileged position as a legal deposit library means that almost any book one cares to read can be found somewhere among its labyrinthine shelves.

While the library does a good job of providing for most students, inevitably, there are always issues. Many courses – take law for example – involve core foundational readings, which the majority of students aim to cover, and no matter how well stocked the library, this will always lead to competition. This scramble for books only intensifies as deadlines rapidly approach and exam season looms.

Add to this the fact that it is often unclear which books need to be prioritised. Nearly every department can point to an issue in the system that sees only a few copies of the most important texts being made available to students, while minor works or outdated editions abound on Stella Search.

Of course, the library itself is not to blame here – the true culprit is the exorbitant cost of academic materials. Due to a lack of mainstream demand, it is not uncommon for a module’s core text to cost upwards of €100. While this naturally impacts the number of copies the library can buy in, it also has a significant effect on students. Often, in a bid to prevent the dreaded library rush, lecturers are forced to encourage their students to buy the books. However, as very few students have a spare €200 on hand, this advice, while well-meaning, is in reality utterly useless.

This is less of an issue for some students than others, with all coming down to the amount of emphasis a course places on outside reading. But in courses that are reading intensive, such as law, history, or philosophy, many students have to resort to buying books second-hand or downloading them online. Neither of these systems is anywhere close to perfect.

Buying used books is perhaps the most common remedy, but the off-hand nature of this process relies on a precarious system of goodwill, timing and luck. These are not exactly factors students want to stake their academic career on.

In a bid to prevent the dreaded library rush, lecturers are forced to encourage their students to buy the books. However, as very few students have a spare €200 on hand, this advice, while well-meaning, is in reality utterly useless

Downloading books, meanwhile, presents further challenges. Ignoring the morality of the situation – most students are as comfortable downloading books as they are streaming films – the downloading process is severely lacking in quality control, something that can hardly be overlooked when writing an essay. A wrong click here or there can result in an outdated edition, or even the wrong text, being downloaded and treated as a reliable source.

On top of this, for someone to take the time to scan and upload books to the internet, they usually have to be relatively popular. For courses like law, which tend to involve readings from niche, Irish-focused books, students generally have to make do with physical copies.

The fact that such a high premium is placed on knowledge itself can only be a bad thing

This might seem largely inconsequential, and in many ways it is, but the annual book-buying ritual is yet another cost to be added to an already expensive college life. Last year, a report from the Dublin Institute of Technology found that the annual cost of living for students living away from home reached nearly €12,500. Roughly a quarter of this came, unsurprisingly, from rent, with books and other class materials accounting for around €630. To put things in perspective, that’s only €50 less than what the average student spends on socialising every year.

The price of academic books, sadly, is unlikely to change any time soon, depending as it does on a vast web of industry-wide factors. Despite its inescapability, however, the fact that such a high premium is placed on knowledge itself can only be a bad thing.

We can all accept that there is a long way to go before education is truly free. In the meantime, is it too much to ask that students stop paying so much for knowledge?