The controversial establishment of a Centre for Middle Eastern Studies in Trinity, paid for by an educational charity founded by Dubai’s deputy ruler, nearly collapsed in 2016 after a dispute over how much influence Trinity would be allowed to exercise over it, The University Times has learned.

Documents obtained by The University Times under a Freedom of Information Request show that serious conflict arose between Trinity and Scotland’s Al Maktoum Institute, the two parties involved in the deal, over the course of a protracted negotiation period.

Trinity announced the launch of the Al Maktoum Centre in July 2019. At the time, Provost Patrick Prendergast thanked the Al Maktoum Foundation for the “generous gift” towards the centre.

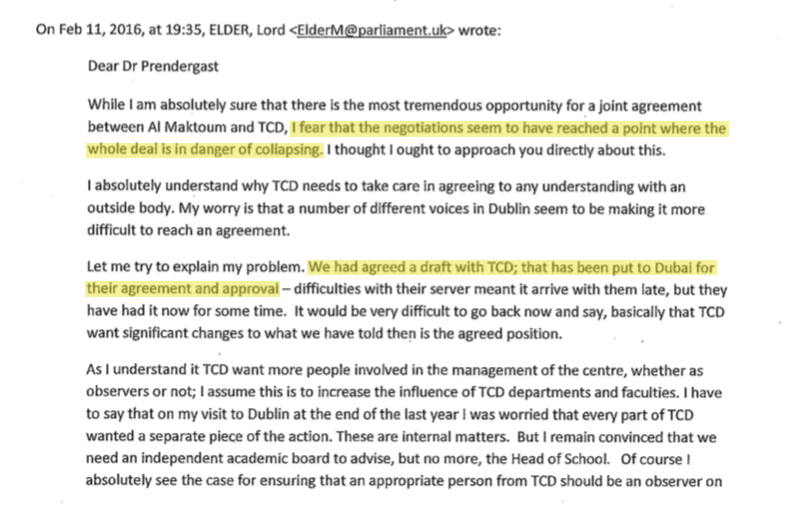

But three years earlier, in February 2016, Murray Elder, the Chancellor of the Al Maktoum Institute in Dundee, wrote to Prendergast warning that the deal was “in danger of collapsing” as a result of Trinity’s desire to increase its influence over the centre.

Elder, a British Labour politician and member of the House of Lords, voiced his frustration that “a number of different voices in Dublin seem to be making it more difficult to reach an agreement”.

“As I understand it, TCD want more people involved in the management of the centre, whether as observers or not”, Elder said. “I have to say that on my visit to Dublin at the end of the last year, I was worried that every part of TCD wanted a separate piece of the action.”

“The whole deal”, he warned Prendergast, “is in danger of collapsing”.

Elder also rebuked the Provost for Trinity’s attempts to change a draft deal agreed by the two institutes, the terms of which Elder said had already been “put to Dubai for their agreement and approval”.

“It would be very difficult to go back and say, basically that TCD want significant changes to what we have told then [sic] is the agreed position.”

It’s unclear what the nature of Trinity’s response was to Elder’s letter, but additional email correspondence obtained by The University Times shows that senior College officials – including Vice-Provost Jurgen Barkhoff – appeared to harbour doubts about the deal’s sustainability.

In a letter sent to Anne Fitzpatrick – the Head of Trinity’s Department of Near and Middle Eastern Studies – after the deal’s completion, Barkhoff wrote that “there were times when I was pretty convinced the deal was dead”.

In an email statement to The University Times, Fitzpatrick wrote that “much of the correspondence referenced reflects the initial negotiations before the final vision took shape and while there were some initial concerns there was never a substantial disagreement, all appropriate parties were included in the discussions, and we are happy that all concerns were met”.

“This was always going to be a Trinity Centre, which means it will operate from within Trinity’s regulations”, she added. “The generous benefaction from the Al Maktoum Foundation presents Trinity with an opportunity to develop an area up until recently absent from the University’s undergraduate curriculum and research themes.”

Elsewhere, Prendergast was forced to reassure the Al Maktoum Foundation in 2018 about Trinity’s commitment to the agreement “in the longer term”.

In an April 2018 letter addressed to His Excellency Mirza Al Sayegh, the Chair of the Board of Trustees of Al Maktoum College and the Al Maktoum Foundation, Prendergast wrote: “As President of Trinity, I established the Department of Near and Middle Eastern Studies, and the Middle East is now a key component in our international strategy.”

He said that College will continue to support the centre at the end of the 10 years during which the Al Maktoum Foundation will fund it.

“At the end of the 10 year period, Trinity College Dublin will continue to support the Centre”, he said.

The documents showed that the project experienced several delays, with senior officials conveying their frustration with the continuous setbacks. Prof Darryl Jones, the Dean of the Faculty of Arts, Humanities and Social Sciences, said in an email to the Provost: “We have acted promptly at every turn – but I guess when you have an endowment of billions, you can move in your own time.”

In March 2016, The University Times reported that the centre would be paid for by a €5.5-million gift from the Al Maktoum Foundation. The organisation was established by Sheikh Hamdan bin Rashid Al Maktoum, the deputy ruler of Dubai and the Minister of Finance of the United Arab Emirates (UAE), in Dublin in 1997.

Sheikh Hamdan is the brother of Sheikh Mohammed bin Rashid Al Maktoum, the ruler of Dubai and the Vice-President and Prime Minister of the UAE.

The new centre will form part of Trinity’s School of Languages, Literature and Cultural Studies and will create four new professorships in the Middle Eastern studies. The centre is aiming to make university-wide academic contributions.

Trinity currently offers several courses based on Middle Eastern culture, including Middle Eastern and Islamic Civilisation.

In a press statement announcing the launch, Fitzpatrick said that the new centre will “no doubt contribute to greater understanding and fruitful relations as students graduate as global citizens and move on with their lives into careers where they can truly have an impact in shaping a peaceful and harmonious future”.

Al Sayegh said in a press statement that “we are very proud to support this initiative and with the association with Trinity College Dublin, with its global reputation for excellence in research and education”.

In 2016, The University Times revealed that 80 per cent of the donation from the Al Maktoum family would be used to pay for staff salaries. The remaining 20 per cent would cover conferences, research centres and the promotion of the centre.

In January, the Dubai ruling family, of which Sheikh Hamdan is a part, was plunged into international controversy when Sheikha Latifa, the daughter of Dubai ruler Sheikh Mohammed, accused him of torture and imprisonment amid a failed escape attempt.

Outgoing Trinity Chancellor Mary Robinson received international criticism for comments she made about Sheikha Latifa after a meeting with Al Maktoum’s family.

Robinson called Latifa – who instructed her friends to release a video accusing her father of torture and imprisonment if her escape attempt from Dubai failed – a “troubled young woman”, after photos of the pair were released by the princess’s family.

Robinson told the BBC that she had visited the family at the behest of Princess Haya bint Hussein, one of the wives of Al Maktoum, to help with a “family dilemma”.

Radha Sterling, the CEO of human rights group Detained in Dubai, accused Robinson of “reciting almost verbatim from Dubai’s script”.

Aisha Ali-Khan, the co-organiser of the women’s march on London last year, said: “It seems clear to me that Robinson has been used by a willing pawn in the PR battle between the UAE ruling family and the rest of the world.”

In the months since, international media outlets have reported that Princess Haya, one of Sheikh Mohammed’s six wives, had left her husband and fled Dubai. Human rights campaigners called on Princess Haya to speak out about the reality of the conditions in Dubai.