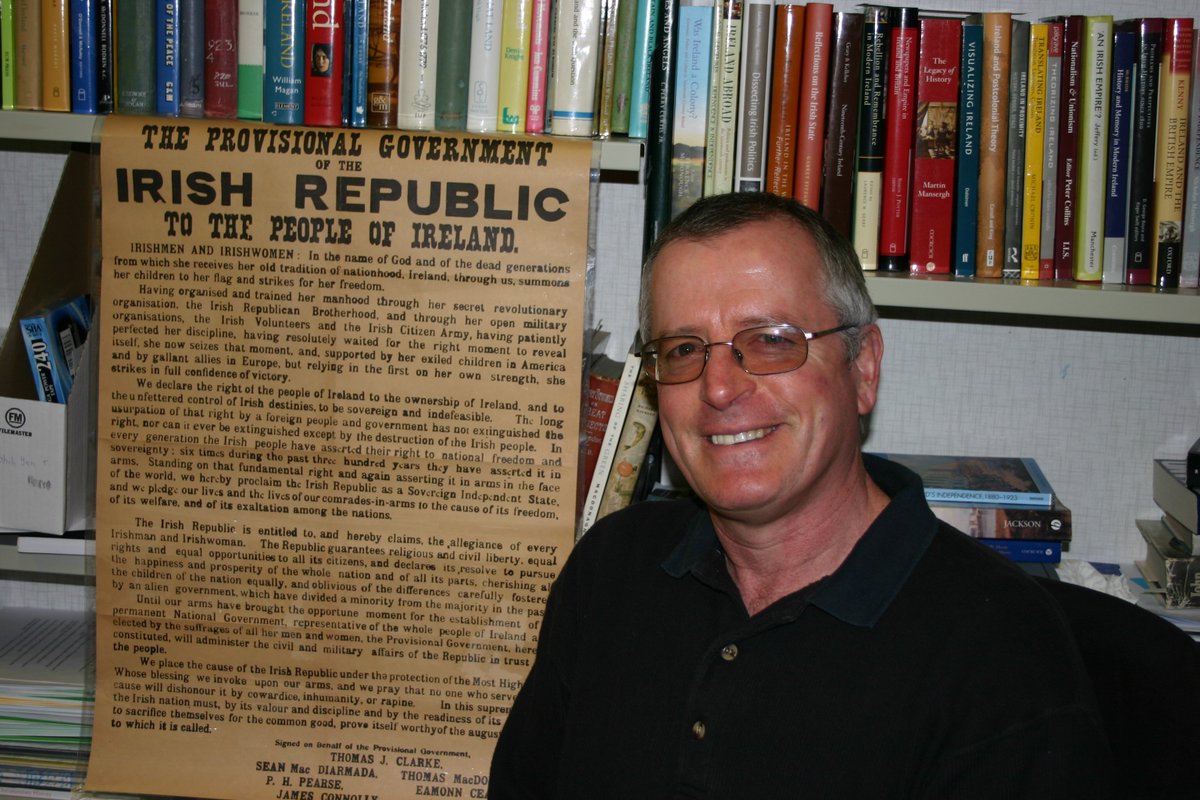

Rory Sweetman graduated from Trinity with a degree in history in 1983 and has returned, 36 years later, to elucidate a piece of the university’s history. Sweetman’s new book, Defending Trinity College Dublin: Easter 1916, details the attack and defence of Trinity during Easter Week 1916, events he says have been misinterpreted and often ignored by historians.

Sweetman describes his time at Trinity as a “challenge”, as he had to rely on his own financial resources to pay his way through college. Born in Ireland, Sweetman moved to New Zealand with his family but later returned to Dublin for his studies. “I was paying for my own degree out of my own resources. When I got here, Trinity decided to charge me a 60 per cent surcharge on the annual fee, as they deemed I wasn’t Irish enough! I found that a little annoying to say the least. I’m tempted to argue that – as New Zealanders saved the college from almost certain destruction in 1916 – they might consider paying me back that money.”

Sweetman argues that Trinity owes a lot of gratitude to New Zealanders and other Anzacs for saving the university from destruction during the rising. However, their defence was not planned and Trinity could easily have been captured by the rebels. That they were there to defend the college when Trinity was attacked is fortuitous.

Sweetman asserts that if Trinity was demolished, the Irish state would have been reluctant to pay for its restoration. “Would Trinity have been rebuilt by the new Irish state when it took possession in 1922? It took them 12 years to rebuild the GPO, longer to rebuild the Custom House and they only managed half of it. The Irish Free State would hardly have spent the millions required to restore the bastion of Protestantism and Unionism; it is much more likely that any new educational institution erected on the site would be ‘Pearse College Dublin’ or ‘De Valera University’.”

When the rebel attack on Trinity began, the Anzacs misinterpreted it as an attack on the Bank of Ireland: “As the rebels are on the rooftops of the Fleet St buildings behind the Bank of Ireland, the Anzacs convince themselves that they are out to rob the bank. This is what they all write home and tell everyone in Trinity after the shooting is over. They have no idea that Trinity itself is the target of the rebel attack.”

The truth was again misconstrued by newspapers who proclaimed that the rebels made persistent attacks on the Bank of Ireland but were stopped by the students of Trinity when they opened fire. In his book, Sweetman hopes to set the record straight: “Looking at these contemporary accounts, historians have tended to dismiss them, knowing that the Bank of Ireland was not attacked during Easter Week. Indeed, as the former home of Grattan’s Parliament, it was a sacred place to the rebels. They don’t – until now – pause to puzzle out what actually happened.”

Sweetman decided to research and write this book after reading a different account of the events in Tomás Irish’s Trinity in War and Revolution 1912–1923. “His thesis is that there was no attack on Trinity, and hence no real defence of it. He concludes that ‘the defence was largely an imagined one’. Now, not only does all the extant Trinity College source material suggest otherwise, but the rebels’ recollections (contained in the Bureau of Military History witness statements) reveal a failed attack in the early hours of Tuesday 25th April 1916. When you add in the letters written by the New Zealand troops, a very different picture emerges of the first two days of the Rising.”

Sweetman’s book is pivotal in reminding us of a moment in history that has been largely forgotten or inaccurately remembered. He argues that Trinity has not paid due attention to the Anzacs who ultimately saved the university from destruction: “As a Trinity graduate and a New Zealander, I was disappointed by the lack of recognition of these events during the recent centennial commemorations. The booklet produced by Trinity on that occasion pays great attention to those who attacked the College, almost none to those who defended it. The commissioned history presents Trinity’s role in the Rising as that of a confused and conflicted bystander, almost itself a victim of the Rising.”

His book also expands our perspective of the Rising by detailing the role that people beyond Ireland and Britain had in the week’s events. “By teasing out the complex events of the first two days of Easter Week, I hope to have restored some balance to the historical record. Appreciating the role of the colonial troops in the drama of Easter Week allows us to see the Rising, not just in terms of World War One but in a global perspective.” Sweetman demonstrates the importance of revising history, and the need to return to sources to question them. Such diligence can change the way we view history.