Lucy Sweeney Byrne is a rising star within Ireland’s literary scene: her poetry, essays and short fiction have been published in Banshee, the Stinging Fly, the Dublin Review, Grist and Litro.

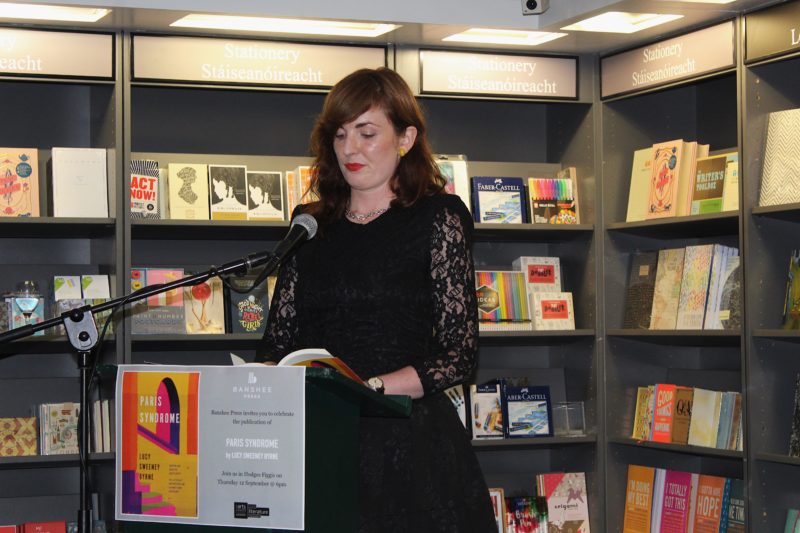

The writer has been present within Dublin’s literary circles for years, and her debut collection of short stories, Paris Syndrome, has already received rave reviews. The writer put her stamp on Irish literary history in May of this year when Paris Syndrome became the first book to be published by Banshee Press.

The collection presents us with a sincere portrayal of what a real, human, 20-something-year-old experiences and feels: the plateaus and plummets in the life of a young woman trying to reach her zenith.

Perhaps the nadir of Sweeney Byrne’s “cultured” 20s came when she visited de Beauvoir and Sartre’s graves in Paris. As documented in her short story “Montparnasse”, the protagonist finds herself underwhelmed as she stands at their graves wishing she wasn’t so warm, that her feet weren’t so sore and that somehow a solemnity would replace the reality of standing beside the graves of two of her favourite writers, while her friend texts her new accountant boyfriend who does bungee jumps for charity and shares his gym statistics with the world.

Speaking to The University Times over email, Sweeney Byrne suggests that the pressure to be someone who knows and has experienced that bit more than everyone else stems from our position in time when everything has been exhausted, including visits to the wonders of the world.

“The world is jaded, and we, being young, refuse to accept our position as late to the party. That seems to be why Millenials, along with the generation after mine, Gen Z, or whatever it’s called, are so psychotically positive, with their Soya milk and handstands and pink hair, while simultaneously on Xanex and crying into their bags of ketamine.”

The world is jaded, and we, being young, refuse to accept our position as late to the party

Sweeney Byrne says that it is the life-affirming likes and comments offered to us by social media that has us all lying in our beds plotting our next caption.

“I am sick of writing (or reading)”, she says, “that anything is caused by ‘the internet’, and am starting to flinch at the words ‘social media’ the way people in Harry Potter flinch when they hear ‘Lord Voldemort,’ but still, it’s true – these things have fucked us”.

No matter how many space cakes we eat in Amsterdam or how many buckets of luminous liquid we drink at a full-moon party, “there is no escaping the self” as Sweeney Byrne succinctly puts it. We have to learn to be with ourselves – an almost impossible feat when we all tend to incessantly compare ourselves to everyone else.

Paris Syndrome explores female sexuality in an undaunted and unswerving manner and Sweeney Byrne exudes confidence and skill when illustrating masturbation and sex. Sweeney Byrne says that “it is an amazing time to be alive, to be working, as a female writer in the West”.

“Now, we can use this creative liberation, both to draw attention to the inherent injustices in life as a female, as well as to delve deeply into the small joys, pleasures, pains, notions and impressions particular to feminine subjectivity. The silence is broken. It’s thrilling.”

Sweeney Byrne’s deft descriptions of the body, as something simultaneously wonderful and vulgar – important and inconsequential – effortlessly weave their way through her compelling narratives. These descriptions invigorate the stories while also providing refreshing portrayals of our nakedness – something we often shy away from.

“I find, literature is so cerebral – so comfortable, and intellectual, and polite, that the characters start to feel as clean and neat and well packaged beneath their clothes as Barbie dolls. I’m not interested in this.”

“Give Walt Whitman the streets of Manhattan, and give me your worn knickers. Give me your stomach rumbles and sore heels and the thin, curled hair on your gooch. Not for the sake of it, not to be crude, or shocking, or to prove myself as some sort of modern anti-prude (how tiresome), but because it’s all there, every day, and it’s all gorgeous, and wondrous, and real, and a part of being alive.”

It is an amazing time to be alive, to be working, as a female writer in the West

The body is also, however, the vessel in which we are contained – and often trapped. Even if you run away to New York to live with an older man that was on your James Joyce walking tour in Dublin, as the woman in Sweeney Byrne’s story Le Rêve does, you cannot transport yourself beyond your loneliness.

Sweeney Byrne tells me about the isolation that she felt in her 20s: “Nobody ever seemed to talk about loneliness as I experienced it – crying and picking spots on my face for an hour and a phone with no messages and binge-watching Man versus Food online for an entire Friday night.”

This loneliness manifests throughout the collection and culminates with the lines of Le Rêve: “She is here, with him, they are both breathing the same silence, which means that they two, at least, are no longer so alone.”

Sweeney Byrne describes her 20s as a “silent scream”, which she evokes through the underlying loneliness and self-doubt that pervades Paris Syndrome. As an English student in Trinity, she took no interest in climbing any social ladder: “Honestly, I was always an odd-bod, and university conversations, all that banter and ego, all seemed like top-notch wankery to me, but I read the books and went to most of the lectures, and loved that.”

It is unsurprising that Sweeney Byrne was not the head of a Trinity society: her self-deprecating humour probably wouldn’t fit in with people who treat their opinions like scripture. Instead, Sweeney Byrne has found her power through writings in which she often reveals her insecurities to the world while using her humour to avoid being overwrought or mawkish.

As the author of Banshee Press’s first book, she has established herself as a writer to look up to and admire. It is her sincerity, brutal honesty and beguiling humour throughout Paris Syndrome that has left her mark on the world, far more than any social status or Instagram post ever could.