Science is a wonderful discipline to study and to devote your working life to, but for many students, as their studies progress, a pertinent concern begins to materialise: perhaps a career in science is incompatible with having a family.

It is an issue that will inevitably arise in conversations amongst friends, both male and female, when discussing a future in academia, but the anxiety-inducing discourse is often swiftly brushed away – no-one wants to think about making such a sacrifice.

Of course, many careers involve long hours, high levels of stress, travel and a scarcity of free time. A career in science, however, poses an additional obstacle: highly specific work for which a stand-in does not exist.

Usually, a researcher cannot be covered by their colleagues should they choose to take leave. After returning, they may find that the rest of their field has advanced, and they have to race to keep up. Despite this, many female scientists manage a successful family life. However, they generally face many more challenging obstacles than their male counterparts because of the way society is structured where childcare is still predominantly viewed as a female responsibility and thus, men seldom feel the same pressures of their partner when raising children.

Maintaining a balance between success and having a family requires a particular intersection of personal traits: diligence, planning and a ferocious need to learn, matched by an equally ferocious love for family.

It’s impossible not to work, and I think most principal investigators would say that it really is necessary to keep some level of work going

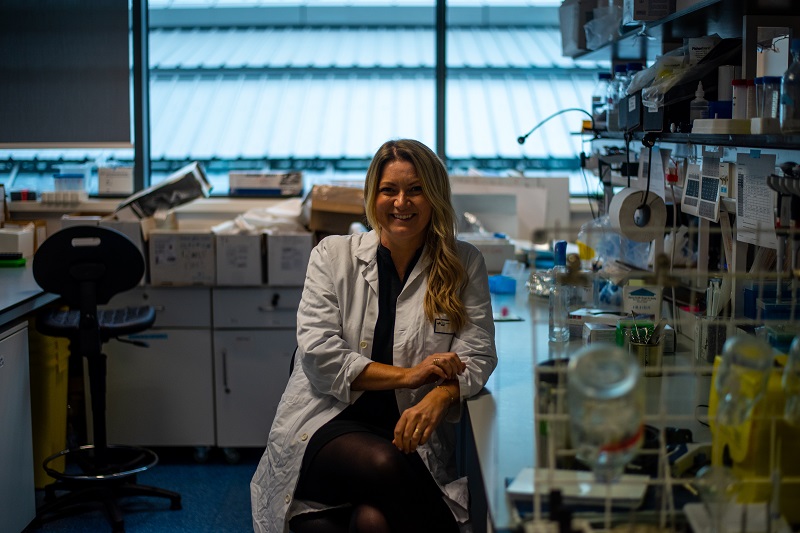

Marina Lynch, a professor of cellular neuroscience in Trinity, explains this to me in her office, which is aptly decorated with pictures of her family. Discussing her ability to have children while maintaining a successful scientific career, she says: “I think it’s really important to spend time with children, but it’s tough. It’s tough for a scientist because the field moves so quickly, and I think it’s harder now even in respect of trying to get back into it.”

Undeterred by the fast moving nature of science, Lynch took her full maternity leave after the birth of both her children, despite the lack of paternity leave available for her husband, who “was still involved in every aspect of the childcare”. Unwilling to compromise, Lynch ensured she could maintain her career while on maternity leave by planning ahead.

“I wouldn’t under any circumstances compromise on either”, she tells me. “For sure it’s possible but it isn’t an easy ride. I think your commitment is probably the biggest thing. And of course you prepare. When you’re pregnant, you make preparations for work as well.”

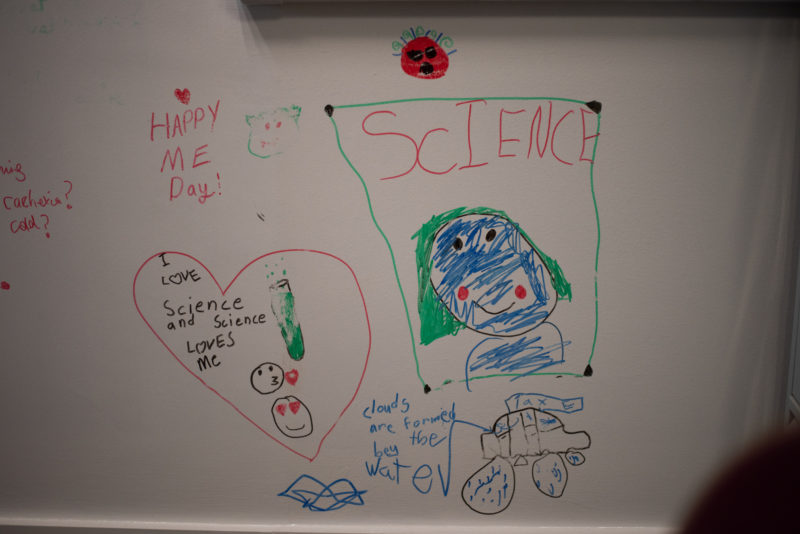

Lydia Lynch’s office, adorned with wall drawings.

Despite being on maternity leave, Lynch still found herself in a position where she had to work, even if “it was at half throttle”: “It’s impossible not to work, and I think most PIs (principal investigators), would say that it really is necessary to keep some level of work going. But it’s hard.”

Nevertheless, Lynch managed, and when I ask her what she would tell young female scientists who want to start a family, she responds with an encouraging and resolute “go for it”.

These sentiments are shared by Lydia Lynch, an associate professor of biochemistry and immunology in Trinity. Lynch’s office is also decorated with family mementos, but the usual photos of smiling children and family members you’d expect to see in an office are replaced by much more creative reminders – wall drawings.

“They’re in here a lot, as you can tell by all the drawings on the wall”, she says with a smile.

A far cry from the sterile whites and silvers of a typical scientist’s workplace, Lynch’s office is bursting with colour thanks to her children, who doodle around her brainstorming on her whiteboard with messages like “I love science and science loves me!”, accompanied by drawings such as what seems to be a germ-bat-human tribrid.

Say I submit a paper to Nature, and it gets rejected. I’m a bit disappointed, but then I go home and everything is put into perspective

With three children, Lynch began her journey as a mother and scientist while still an undergraduate science student. She then had her second child as a PhD student and her third child as a postdoctoral researcher.

It is Cliona O’Farrelly, professor of biochemistry and immunology in Trinity, who Lynch perhaps had most to thank in her early years as a mother academic. While supervising Lynch’s PhD, O’Farrelly supported her fiercely in her choice to have a family, insisting she be paid during her maternity leave, and work a four day week on return. “You’ll be happier – and a happy student does more work”, O’Farrelly told Lynch.

Lynch successfully completed her PhD and went on to secure two prestigious fellowships, which allowed her to move to Boston, where she became pregnant again. She took full maternity leave of six months, but it wasn’t a move that decelerated her scientific trajectory: Lynch now has an established lab at Harvard, as well as Trinity.

Like Marina, Lynch was unable to completely cease work during her leave: “I still went to lab meetings every week just to keep up with things. If I was to take maternity leave now as a PI, I would work more”, she says. “I’d probably still hold lab meetings, I’d definitely still read papers, I’d give people direction. So I’d still work if I was on maternity leave.”

While it may be difficult to juggle all these balls in the air at a time that is physically and emotionally taxing, Lynch strongly encourages starting a family as a scientist, insisting that despite the challenges, it is more than worth it: “It just makes you happier. For example, say I submit a paper to Nature, and it gets rejected. I’m a bit disappointed, but then I go home and everything is put into perspective.”

“It’s just not that important. My kids are so much more important. And I think if you didn’t have that, you’d think a lot about failure, because science is full of failure.”

As O’Farrelly was a supportive role model to Lynch, Lynch is now herself a role model to her own lab members, one of whom conveniently happens to be passing by her office during our interview.

Lynch calls in Lydia Dyck, a postdoctoral researcher, and says of marriage and family that “I tell them to enjoy it. Enjoy your maternity leave, and in my opinion, it’s the best thing in the world to happen, so please god it happens for them. It doesn’t affect your career at all”.

Lynch asks Dyck whether she was worried about potentially starting a family, to which Dyck shyly admits: “Not now, but before I probably did think it would be hard because you’re told you have to choose either family or career, and I think working with you is the first time I had a role model, someone who showed us it was possible. You were the person who showed us that it was fine.”

The dynamic nature of science gives the field a veneer of unapproachability for women who wish to spend time with their families. But with role models such as Lynch there to guide them, and male partners to support them, women in science do not have to feel weighed down by their families. Instead, they can experience for themselves that having a family makes them better scientists. So, while the reality of having a family while maintaining a successful scientific career is difficult, it is certainly doable.

And that is a fact that can inspire any woman pursuing a career in science.