Three years on from the Brexit referendum, thousands of students ineligible to vote back in 2016 will be making their voices heard in a general election that’s set to be one of the most pivotal and polarising in the country’s recent history.

The principle issue of the election? You guessed it. Brexit.

With 73 per cent of those between the ages of 18 and 24 voting to remain in 2016, it would seem likely that this will transfer into votes for pro-remain parties. However, young people are statistically less likely to vote than any other age group, meaning that their turnout will be critically important, particularly for pro-remain parties.

For the people who were teenagers when the Brexit referendum was decided three years ago, this general election will be an opportunity to have their voices heard for the first time, and the way they decide to cast their votes will likely have a direct impact on the future of their country.

The tumultuous political events of the last several years have translated into an increase in the number of students studying politics. The “Brexit effect” has seen the number of applications to study politics in UK universities surge by 28 per cent since the referendum.

This renewed interest in politics has come at a time when the language and rhetoric surrounding Brexit is more divisive than ever. Such is the intensity of public vitriol towards certain politicians that some members of parliament have been forced to take extreme precautions for their own protection. For instance, Anna Soubry, an MP and the leader of the Independent Group for Change, has stopped holding open surgeries for her constituents, as the risk these events pose to her life is too severe.

After Anna Soubry, one of our nearby politicians, had retweeted it, all of those people who attacked her started to harass me as well

This backlash has bled into spaces that were previously considered sanctuaries of free speech and open discourse: universities. Since legislation passed placing a legal obligation on universities to encourage their students to vote, some academics have found themselves the victims of harassment.

This was the experience of Prof Carrie Paechter, the director of Nottingham’s Centre for Children, Young People and Families. After tweeting that students in the UK can be registered to vote at both their term address and their home address, and they can decide which constituency they would like to cast their vote in, Paetcher was subjected to severe harassment on Twitter and was met with accusations of voter fraud.

Now, speaking to The University Times, Paechter says: “After Anna Soubry, one of our nearby politicians, had retweeted it, all of those people who attacked her started to harass me as well.” While the negative discourse that is dominating British politics at the moment certainly seems to be one of the main factors behind the backlash academics are facing, it is clear that there is an element of misogyny involved as well. Female politicans in the UK are receiving more rape and death threats than ever before. A man was recently jailed for sending a written death threat to Soubry, in which he referred to the murdered MP Jo Cox.

This worrying rise in harassment is evidence of the polarisation of political views in the UK. Paechter, though, remains strong in her convictions – she says she believes that voting is a “civic duty”, and adds that during strikes earlier this month, she knew of colleagues taking iPads and laptops to the picket lines and encouraging others to register to vote.

The efforts of academic staff to mobilise voters have been reflected in the actions of some of the UK’s students. Molli Cleaver, the president of Reading University Students’ Union, tells The University Times that it often feels like students “don’t have a platform where we can share our voice and be listened to, particularly in politics”. She says that the rule mandating universities to encourage students is a reflection of the government taking the youth vote seriously. “Now there’s an obligation. It highlights the importance of getting students to vote. There’s a sense that universities will take it more seriously.”

Cleaver says the 2017 general election – when Labour won the Reading East constituency for the first time in 12 years – changed the perception of how young people can impact politics. “We have proven that when students come together and they decide to vote that tangible change is made.”

As interest in politics hots up in the run-up to the election, Cleaver is working with Reading University’s student branches of the Labour Society and the Conservative Association to set up a mock election debate. Organising this kind of on-campus event encourages students to engage in politics, she says. They add a real-life dimension to TV debates between party leaders. This direct parallel between on-campus debates and those shown on television is one of the ways in which universities, their students’ unions and political societies are encouraging a culture of participation in the political system.

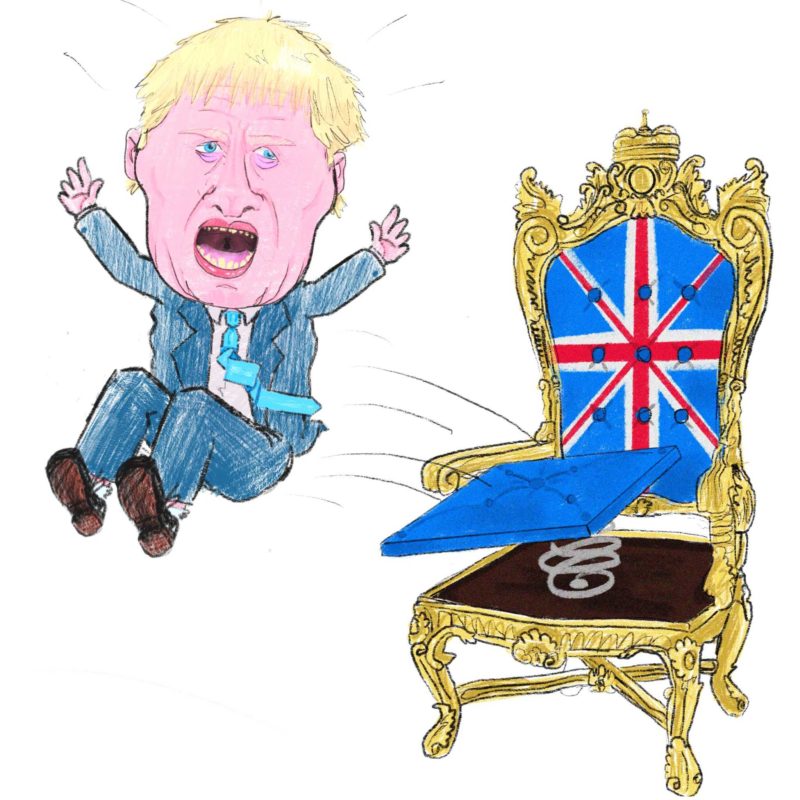

Boris Johnson has become a figure synonymous with Brexit, and the UK’s new explosive political discourse, since the lead-up to the 2016 referendum. His prime ministership, however, has been wracked by controversy, and his future as a politician will undoubtedly be decided by the future of this election.

And if evidence was needed that we’re in a new age of political debate, it’s easily found – in Johnson’s own constituency. There, students and Labour activists are campaigning to achieve something that has never been done: unseat a sitting prime minister.

Johnson, who caused ructions when he expelled 21 members of his own party in September, currently has a majority of 5,034 in his constituency of Uxbridge and South Ruislip – the smallest majority of any prime minister since 1924. His closest rival is the Labour party candidate, Ali Milani, who requires a five per cent swing in his direction in order to get elected. With his alma mater, Brunel University, located within the constituency, many have speculated that student turnout will be very important in the election.

Jemmar Samuels, a politics and sociology student at Brunel University, tells The University Times that Milani’s roots in Brunel University – as both a student and the president of the Union of Brunel Students – ”appeals to voters”.

“Ali Milani has a history here and as a former vice-president of NUS [the National Union of Students], he’ll definitely win over students”, she says. “I personally see any election as important to everyone, but especially for students, because the way our education system is run can dramatically change by voting one way or the other.”

For students and young people, a hard Brexit means fewer opportunities and living in an inward-looking society

Samuels, who says she’s sharing her own views rather than her university’s or her union’s, believes that the legislation mandating universities to encourage student voting could be majorly significant. She references a recent media article that “revealed there are 20 universities located in some of the most marginal Tory seats. If enough students registered and voted in these places then there would be a number of MPs unseated”.

Samuels believes that this would not only have a significant impact on the election, but would also challenge the perception of young people being uninterested in politics.

After nine years of Conservative rule, many students are hoping to vote tactically in order to increase the chances of removing them from power. Websites recommending which party to vote for in swing constituencies have already been shared widely among students.

But it’s not just voters who are considering the ups and downs of tactical voting. Parties and candidates themselves are also making strategic decisions. Anti-Brexit parties Plaid Cymru, the Liberal Democrats and the Greens have made an electoral pact in 11 out of the 40 seats in Wales. Pro-Brexit parties are doing the same, with the Brexit Party announcing that it won’t stand in any of the 317 seats won by the Conservative party back in 2017.

For our Future’s Sake, or FFS, is a student-led movement campaigning for a people’s vote on Brexit. The group was first launched in 2018 at the NUS National Conference, and today represents approximately 60 students’ unions and over 900,000 students. In an email statement to The University Times, the group’s co-founder, Amanda Chetwynd-Cowieson, highlights the importance of student-led movements. “Students have often been at the forefront of driving positive change and challenging the wrongs in society. Often this is through movements such as FFS, set up by a group of mates in a pub, after getting annoyed at the status quo.”

Discussing the frustration experienced by many UK students as they watched the mayhem unfold with little or no say on the matter, she says: “For us, it was having seen numerous debates on Brexit totally dominated by middle-aged, privileged white men – with no references to young people, barely any women, people of colour or people with regional accents – and a complete lack of acknowledgement of the fact that the vast majority of under-30s voted to remain, and would do so again.”

Chetwynd-Cowieson emphasises the importance of the December general election for students, saying: “If Boris Johnson gets a working majority in parliament, he will have a free pass to deliver his hard Brexit deal, and this is a million miles away from the promises made in 2016. In particular, for students and young people, this means fewer opportunities and living in an inward-looking society.”

Members of For our Future’s Sake believe that Brexit represents a seismic shift in what the future of the UK looks like – and, for them, it isn’t a bright one. As Chetwynd-Cowieson says: “Any form of Brexit will have a negative impact on our country: there is no such thing as a jobs-first Brexit, a migrants-first Brexit or a Brexit that benefits the UK’s education system. This general election is a chance to send a clear message to the privileged elite driving Brexit forwards and all students should absolutely take this chance.”

The group is made up of a collection of young people who believe that the UK is better off remaining in the EU. The team has members from across the UK – its mobilisation officer, Rosie McKenna, hails from Ballymena in Northern Ireland. McKenna tells The University Times that a convergence of unusual factors at this election – the rising role of students, as well as the fact that they can choose tactically whether to vote at home or in their university constituencies – amounts to “an election-skewing bombshell just waiting to go off”.

McKenna says that the creation of For our Future’s Sake comes at a moment when “more and more young people are realising how much agency and power we have within our political system – and how much politicians rely on the myth that we are a generation of disengaged, apathetic snowflakes”.

If students living in Britain have been largely overlooked in recent times, then their peers in Northern Ireland have probably been considered even less. But it looks likely that students up north will be going out in large numbers to vote on election day.

Not everyone has forgotten their importance, either. Niamh McCay, the education officer of Trinity College Dublin Students’ Union, has been working to tell Trinity students from the north that they can apply for a postal or proxy vote, which would allow them to participate from Dublin.

McCay emphasises the importance of this election for students and young people from Northern Ireland, highlighting the uncertainty surrounding their rights, the border and the freedom of movement across it. Northern Ireland has been without a devolved government for over 1,000 days, but McCay says that “it might seem a bit redundant that we’re voting at this time, but we’re voting for who will represent us in our local area”.

It is clear that getting students to vote is important to McCay. She says that when universities encourage their students to register to vote, elections become “a different ball game”.

While we do not yet have definitive proof that the legislation requiring universities to encourage student voting has had the desired effect of increasing young people’s engagement with politics, early signs indicate that this is the case. At this stage of the election campaign, 1.36 million people aged under 35 have now registered to vote.

This figure is almost twice as high as it was at the same time in the 2017 election campaign, suggesting that the turnout and voting intentions of young people will have a major role to play in this election – and, indeed, in Britain’s future.