One of the student short films shown at the Silk Road Film Festival seemed to typify what the entire festival was about. Charline Fernandez’s documentary Maria follows the director’s grandmother as she returns to the sites of her childhood. When the film was shown at the festival, the eponymous Maria Belmonte was in attendance, as was much of her family. She is a highly spirited woman, a grand-dame of sarcasm – “thank goodness we have grandchildren like you, Charline” – but her presence and her story spoke volumes about the festival.

The festival, which ran from January 21st to 25th, had a lofty roster of missions and visions that all revolved around a modern notion of cross-cultural encounter and journeys into difficult terrain, showcasing young talent, experiencing cinema in groups and, finally, uniting people of different backgrounds.

On its website, the festival describes itself as a “caravanserai”. The word comes from the Persian words “kārwān” meaning caravan and “sarāī”, or “sarā”, meaning palace, mansion or inn. The Oxford English Dictionary lists it as “a kind of inn in Eastern countries where caravans put up” – caravanserai refers to a stopping-place for travellers in which they can rest and shelter but also forge contact with others.

This description perfectly encompasses the festival’s international roster. The eighth iteration of the Dublin festival coincided with the Chinese New Year celebrations. This is fitting, as the festival was partially funded by the Chinese embassy and there were, of course, many Chinese films screened at the festival.

The festival is quintessentially Dublin. It makes use of the city’s cultural spaces and there’s so much going on

However, the occasion was far from a propaganda machine, as it featured short films and documentaries from dozens of other countries, and feature films from Iran, Turkey, Italy and Hong Kong.

The festival’s origins, however, are a little closer to home. Siblings Carla and Delwyn Mooney from Portarlington, Co Laois, are the co-founders of the Silk Road Film Festival. Both founders were internationally inclined long before their ideas for the festival were spawned – in college Carla studied international business with French while Delwyn studied film, advertising and art direction in Barcelona.

Somewhere along this route, Delwyn met Iranian director Khashayar Mamoodabadi. Years later, the three would come together to make an Iranian documentary called The Secret of Permanency.

While the documentary’s IMDB synopsis – “Secret of Permanency follows the steps of a western girl on a spiritual journey to Esfahan, Iran, wandering through the Bazaar Mosques and Palaces she awakens the echoes of ancient Persian history and civilization” – perhaps raises Orientalist alarm-bells, the festival deserves no such criticism.

While making this film, the siblings befriended other Iranian filmmakers, all of whom were “finding it hard to get their films screened outside of Iran”, Carla tells The University Times. On returning to Ireland in 2012, the pair wanted to change this and they set out to create something that would give a platform to filmmakers from Africa, the Middle East, Asia and Europe. Inspired by the history of the ancient trade route, the Silk Road Film Festival was born.

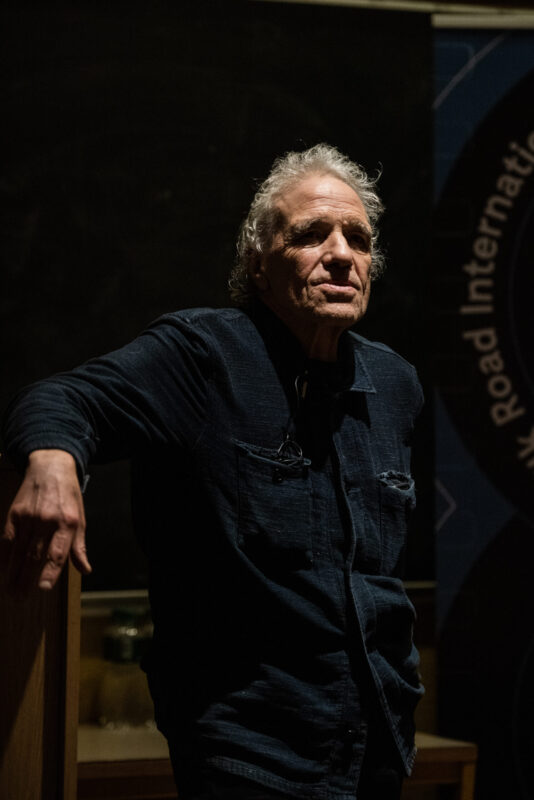

The festival has continued to grow year after year. This year it managed to attract Abel Ferrara, the acclaimed and somewhat controversial director, who did a question and answers session following the Irish premiere of his latest film Tommaso on Wednesday, January 22nd.

The following day, Ferrara conducted a lively masterclass in the Jonathan Swift theatre. Michael Lee had the unenviable honour of introducing Ferrera. Lee took this opportunity as a chance to serenade Ferrara with lavish praise. As Lee began to talk about Ferrara’s “uncompromising vision”, Ferrara cut him off. “I’m standing right here”, he said. “Don’t talk about me like that. How’d you get this job anyway?”

Filmmaker Abel Ferrara delivered a masterclass that was a festival highlight.

Ferrara isn’t modest. He does everything on his own terms. When asked if he feels more pressure to have a diverse crew in the wake of “#MeToo”, he blithely replied that “I’ve always worked with female producers” because “I don’t want to walk on set and feel like I’ve enlisted for the army”.

Ferrara is a natural raconteur and recounted tales with humour and verve. Everyone was laughing as he recalled being high in Dublin in the 1990s when he met “Bone-O’s band” and when he talked about shooting his 1993 film Body Snatchers (1993) in “the crack capital of the south”.

The director has been sober for seven years now but he talked candidly about his previous drug and alcohol abuse. He recalled his old collaborator Zoë Lund thinking that “heroin was the elixir of life” before her untimely death and he talked of others who had been destroyed by alcoholism. Ferrara’s masterclass was a festival highlight.

The festival is quintessentially Dublin. It makes use of the city’s many cultural spaces and there’s simply so much going on that it’s impossible to experience even half of the events. A couple of the feature films were screened in cinemas like the Odeon, Point Square and the Irish Film Institute, and tickets for these screenings were the same price as a standard cinema ticket. The majority of events, however, were free.

These screenings were held in Trinity’s Arts Block, the Hugh Lane gallery and even the Brooks Hotel’s private cinema.

Brooks Hotel’s private cinema lent a unique intimacy to these screenings. Unfortunately, the only film that we saw there was the disappointing and confusing Long Time Ago by Turkish director Cihan Sağlam. The venue had an air of familiarity about it, though, so when somebody piped up at the end to ask “what was going on with that dead body at the start?”, you felt comfortable enough to say, “no idea, mate”.

It was nice to see Trinity’s own, underutilised theatres play host to so many of the festival’s events. On three separate nights Trinity’s theatres screened a two-and-a-half-hour collection of student short films. Reading through a list of brief descriptions of the short films to be shown, searching for an organising principle in their curation, one would have struggled: impressive variety, to say the least, was plain to see.

It was nice to see Trinity’s own, underutilised theatres play host to so many of the festival’s events

Regardless of theme or content, watching a full complement of short films revealed the great artistry in the depths of inventiveness that the filmmakers had plumbed in order to tell stories through a restricted time limit. The experience, by the end, was perhaps akin to the feeling one might have should they choose to remove the facades of all the houses of a terrace, to inspect the great mélange of interior decorating the residents had used.

These screenings demonstrated the high-quality of international student filmmaking. These events felt representative of the festival as a whole: they emphasised its international dimension, its determination to be a platform for struggling filmmakers and its concern with the future of filmmaking.

Hao Zheng’s The Chef, for instance, is a commentary on our most major labour dilemma: people versus artificial intelligence. In the film, a Chinese chef, Pu, is faced with the task of training up a “humanoid”, a robot in the guise of a preppy, chino and polo-shirt-wearing American, who proves not only more efficient, but more amenable than Pu’s other, human trainee. This 20-minute film demonstrates the pressing contemporary economic and moral questions our politicians must address as automated labour continues to diminish the need for people to be doing certain jobs.

Austrian director Nicolas Pindeus’s Life Between the Exit Signs is similarly powerful. Pineus has spent the last five years studying under Michael Haneke and clearly shares his mentor’s interest in psychologically and emotionally scarred characters. The film opens with a shot – scrubbed pale by uncompromising morning sunlight – of a boy visiting a bed-bound figure with flowers. Instantly we are transported into a visual meditation on the impact of grief on the human psyche as the film explores the ways in which our current relationships can deteriorate based upon unresolved issues. The film packs an emotional punch and possesses a confidence and a maturity that seems beyond the director’s years.

If there was disappointment, it didn’t stem from the festival itself, but rather from its attendance. From what we saw, most events (excluding big ones, such as Ferrara’s masterclass) were typically attended by fewer than 10 people, and the screenings of the short films were predominantly attended by the filmmakers and their friends and family. If people don’t want to attend the Silk Road Film Festival, that’s fine. But we cannot continue to complain about the cost of events in Dublin, or look starry-eyed to other vibrant, cultural hotspots, when we have such terrific, free events within the walls of Trinity’s campus. Hopefully next year more people will immerse themselves in this wonderful festival.