In a varied and colourful political career there have been quite a few pivotal moments. But one in particular that automatically springs to mind goes back to the beginning of the 1970s.

At that time, the troubles in Northern Ireland were really getting underway and I, along with a group of other concerned citizens in Dublin, started an organisation called the Southern Ireland Civil Rights Association.

This was intended to provide moral support for the beleaguered Roman Catholic and nationalist minority in the north. At the first meeting, I became exasperated by the smugness of the platform party. They seemed to suggest that discrimination was an entirely Ulster problem and that we, in the south, were far too refined to get involved in anything like that.

I decided to interrupt this self-congratulatory mood, but I also had another, more human, reason for wanting to intervene. On the other side of the aisle, I had spotted a very handsome young Dutch man and I thought: “How can I raise the flag and let him know that I am gay?” So, I stood up and said: “You have very complacently maintained there is very little discrimination in the south. On a religious level of course, that is true.

In the end, we took the fight to the European Court of Human Rights, where we won by only one vote

The difference between the north and ourselves is that, while in the north, the communities are fairly evenly balanced, in the south the Protestant minority is very small. It is also financially very strong, so there are good reasons on the part of the authorities not to antagonise them.” But, I announced, “I am also a member of another minority. I am homosexual” (we didn’t know the word gay at that point).

This had the desired effect. The Dutch man came over straight away and started talking to me. But it turned out that he was completely heterosexual and a devout Roman Catholic. However, we remain friends until this day, so it was a positive. The other achievement was that I persuaded the Southern Ireland Civil Rights Association to adopt as one of their causes reform of the criminal law directed against gay men.

And this single decision led to a whole sequence of events. In 1973, in Trinity, there was a conference about sexuality. However, most of the debate turned exclusively on the subject of homosexuality. As a result, various groups were set up, the Union for Sexual Freedoms in Ireland and a local group centred in Trinity called the Sexual Liberation Movement.

There were about 10 or 12 of us, all gay except one indeterminate person. We spent our time writing letters to the newspapers demanding contraceptives. In those days condoms were not necessary for gay men prior to the Aids epidemic. I protested and led a rebellion, the consequence of which was the formation of the Irish Gay Rights Movement. It continued very successfully, for some time, under my chairmanship, until there was a palace revolution.

As a result of this, I founded the Campaign for Homosexual Law Reform, which went on to gain strong supporters, such as Prof – and later President – Mary McAleese. This group took control of the legal action I had just launched against the Irish state for reform. Ultimately, we got a very good judgement from Justice McWilliams. He accepted all the evidence we had produced, saying that there was a surprisingly large number of gay people in Ireland, and that they weren’t child molesters nor less intelligent than the general population.

The aforementioned Mick got out and took a look, before replying: “Whorrabowrra. I don’t give a bollix, a picket’s a fucking picket mate”

Then, at the end, he took a violent swing and concluded that, despite all of this, the Christian and democratic nature of the Irish constitution necessitated that he find against us. This led to the Supreme Court, where the court decided against me by three votes to two.

The Chief Justice provided a completely nonsensical judgement that ignored the principles of the law but we got two very good dissenting judgements. In the end, we took the fight to the European Court of Human Rights, where we won by only one vote, with the Irish judge voting against us. However, a win is a win.

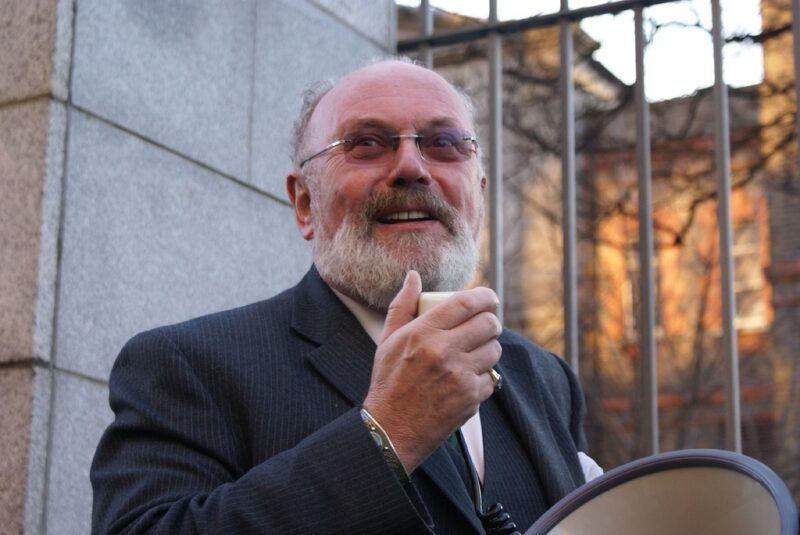

One of the more amusing aspects of the decision to commit to gay rights was that I was on the first-ever gay march in Dublin. There were 8 or 10 of us. First, we picketed the British Embassy as the source of the laws, and then the Department of Justice on St Stephen’s Green. We all had placards and mine featured the double entendre “Homosexuals are Revolting”. The Minister’s secretaries were all up at the first-floor windows looking at us with astonishment.

The 46A bus nearly went through the railings of the Green when the driver saw our placards. Then a lorry drew up, and the Minister’s new carpet was flung out on the pavement. A helper – a big burly man – got out, took one look at us, and said back into the cab “Jasus Mick, fucking queers”. The aforementioned Mick got out and took a look of his own, before replying to his companion: “Whorrabowrra. I don’t give a bollix, a picket’s a fucking picket mate.” With that, he took up my placard and walked around with us for half an hour. I thought it was a wonderful example of working-class solidarity.