The concept of “hegemonic masculinity” was first expressed by Australian sociologist Raewyn Connell in the 1980s. Today the concept is more commonly known by a term that’s now loaded with meaning, and deeply contentious in some parts: toxic masculinity.

Referring to a practice that legitimises men’s dominant position in society through harmful practices like emotional repression, toxic masculinity has many detrimental effects on mental health among self-identifying men-including high levels of depression and anxiety. Men are four times more likely to die from suicide than women.

The effects of toxic masculinity can be seen all over the world and it’s a conversation that men are increasingly beginning to have with themselves.

But if the toxic masculinity discussion is expanding, it’s in the US universities that it has been examined in the most depth. Many American universities even have curriculums designed to help men discuss the subject – like the one in Brown University, Rhode Island. There, the university has “worked with fraternities, athletic teams, acapella groups, student organisations and residence halls”, Mark Peters, the college’s director of community dialogue and campus engagement, tells The University Times in an email.

Even though gender norms are socially constructed, many men have internalised them to the point that they believe that they are core to who they are

Peters adds that the college has “found that collective group commitment to shifting norms gives permission to students to explore new ways of thinking, knowing and being”. He says that “even though gender norms are socially constructed, many men have internalised them to the point that they believe that they are core to who they are as individuals. I’ve found that if I talk about living our lives in ways where we are not causing harm to others or ourselves, I can get to the roots of toxic masculinity without a wall going up”.

But Brown University doesn’t just talk at its male students – it lets them talk back. Peters writes that the college’s “Masculinity 101 Discussion Group holds space for folks who are open to questioning what they have been taught … students in the group talk about relationships, hook-up culture, families, mental health and really everything under the sun because our whole lives intersect with our notions of masculinity”.

So far, then, so practical. But what of the theory of toxic masculinity – and the scholarship that’s evolving around it? Andrew Reiner, a lecturer in Towson University’s College of Liberal Arts in Maryland, delivers a seminar on this very subject, and he’s writing a book on it, too. He tells me his research carried out in his classroom shows how fathers raise daughters differently than sons, and the damaging effects of this difference. Female students surveyed were more likely to identify their fathers as a nurturing presence as well as pushing them to be competitive. Male students, predictably, were more likely to answer that their father encouraged them to be successful without being a nurturing figure.

“It is more pronounced as boys get older”, Reiner says. “The expectation is that parents feel they are doing their sons a huge disservice if they don’t socialise them to be confident men and hide their vulnerability.”

And if the problem exists at a familial level, then it’s also a systemic issue: Reiner points out the relative lack of resources available to men’s groups when it comes to having a conversation about toxic masculinity. “In the States, most men’s groups that exist on college campuses are to teach other men about sexual assault. What they don’t teach is how to understand and how to process emotions – which contributes to the epidemic of boys and young men falling behind in school and not going to university at the same rates as women.”

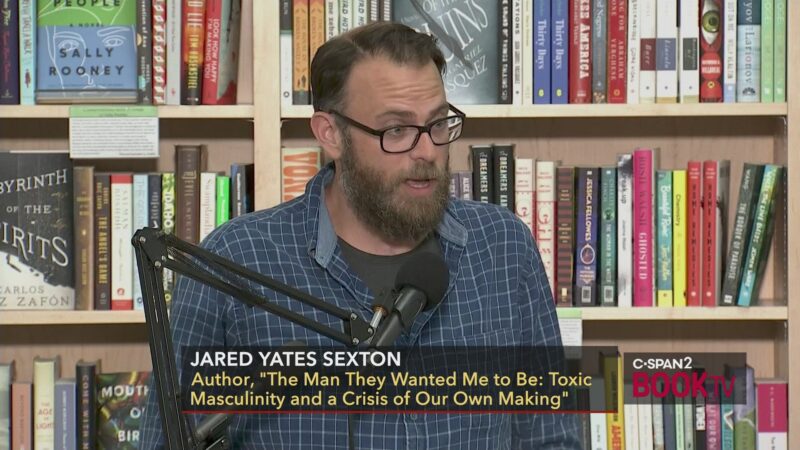

In a field that’s still in its relative infancy when it comes to academic study, there are varying viewpoints on the causes and effects of toxic masculinity. But among those at the forefront, there’s a great deal of consensus. Jared Yates Sexton, an associate professor at Georgia Southern University, has penned several books on social issues – including The Man They Wanted Me to Be, in which he discusses the unrealistic and damaging expectations often placed on men.

“It’s impossible to live up to those expectations”, Yates Sexton writes bluntly in an email. “Men have as many feelings as women, and in some cases even more. But they’re told constantly to suppress them for danger of being rejected or punished physically and emotionally.”

Ireland, then, could have a long way to go to catch up with America’s scholarship around toxic masculinity. But students’ unions are actively seeking to pave the way in shifting the terms by which we discuss the concept of maleness. Trinity itself has launched a new male group, Lads Talk, supported by Trinity College Dublin Students’ Union (TCDSU). The union’s welfare officer, Aisling Leen, says that “men’s mental health is a topic that has been on the SU’s agenda for a few years now, with past welfare and gender equality officers putting huge work into campaigns”.

Shane Hayes, who runs the group, writes in an email that “there’s been a void left by the complete degradation of traditional concepts about masculinity”.

“I feel like having a place for guys to talk will allow us to refill that void with healthier, more balanced ideas about what being a man is.”

Men have as many feelings as women, and in some cases even more. But they’re told constantly to suppress them

“I believe that there is now scope to look at masculinity in a more holistic sense”, Leen says. The group, she adds, is “not intended to be therapeutic but to allow men to discuss whatever it is they want to discuss in an open, comfortable setting”.

And if it wasn’t clear by now, it’s a discussion that needs to be had – by everyone. Ana Sainz de Murieta, the PRO of Trinity’s Dublin University Gender Equality Society (DUGES), tells The University Times that for DUGES, toxic masculinity is “an important issue – but for some reason people don’t see it as a feminist cause or something that feminists care about, even though we do”.

“I’d say that’s why we can’t get many men to go to our events and be an active part of the society, even if gender roles affect them as much as they affect women.”

And Sainz de Murieta provides a concerning real-world example of the need for a greater awareness of the perils of toxic masculinity when she tells me about an incident that happened last term in her course group-chat: misogynistic memes were posted, in an episode she said left her and many of her female coursemates feeling “really vulnerable and hurt” – and questioning whether they should even be on the course at all.

It’s clear, then, that we’re still only getting to grips with the issue of toxic masculinity – and there are many who deny its legitimacy. One way or another, it seems the world needs to continue investigating and discussing it – both inside and outside the classroom.