For many of us, it likely feels like forever since Ireland went into lockdown by degrees, and people are adapting to a new normal. But these are deeply strange times, which history could remember as era-defining.

Literature can be a great mirror, reflecting what we’re feeling. That’s why The University Times is launching a new series asking Trinity’s English professors to tell us about their lockdown reading.

Dr Philip Coleman

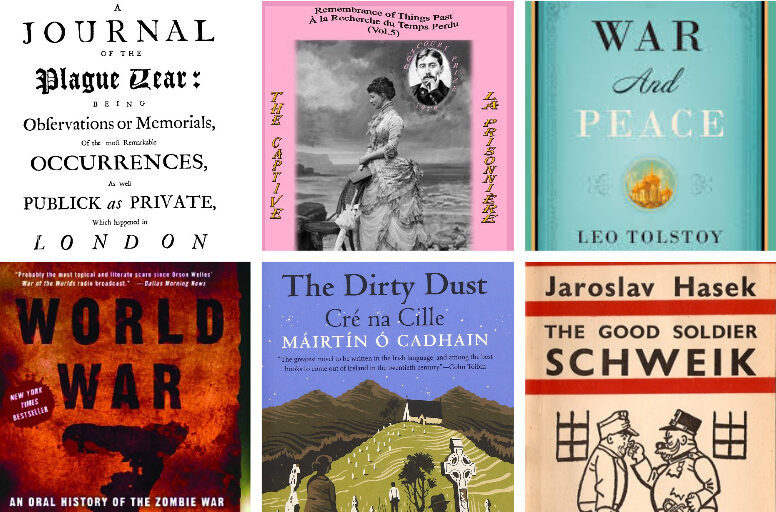

When the coronavirus crisis really started to hit home a lot of people started talking about it as a kind of plague. Fintan O’Toole riffed on the idea in the Irish Times, for example, invoking the Old Testament. Sometime in March 2020, therefore, I thought it was the right time to read Daniel Defoe’s Journal of the Plague Year, published in 1722 but based on the Great Plague of London 50 years earlier. It’s remarkable, reading Defoe, how little has changed in the intervening centuries…

For pure distraction during these times, I’ve also been reading what Adam Gopnik described as “an imperfect” translation of Proust’s À la Recherche du Temps Perdu that is, for all that, “a classic in English”. C K Scott Moncrieff’s translation of the French original is a remarkable achievement in lots of ways, but there is nothing like reading a few pages of it in the evening to take one’s mind away from all the awfulness going on in the world right now.

Two more recommendations, based on current bedtime reading. Another translation, this time from the Irish of former Trinity professor of Irish Máirtín Ó Chadhain, Cré na Cille, rendered as The Dirty Dust in an uproarious translation by Alan Titley. And the short stories of Lucia Berlin, an American writer whose work I was introduced to by a student this year (Holly Moore) and look forward to learning more about when the current situation passes.

Dr Bernice M. Murphy

Zombie narratives are stories about contagion, and about how people (and institutions) behave when the normal rules no longer apply as a result of such an outbreak. Inspired by George A Romero’s Living Dead films, World War Z by Max Brooks is a panoramic “oral history” set in the aftermath of a devastating global pandemic that turns the “infected” into undead ghouls. Much of the story depicts pre-existing systems (particularly capitalism) collapsing under the pressure. Crucially, however, this is also a tale of resilience, reinvention, and adaptation, which makes it perfect lockdown reading.

Dr Carlo Gébler

Although remote teaching takes more time than fact-to-face teaching, I am managing to read. I’m not going for comfort. Nor am I striving to have my heart lifted. No, I’m going the other way.

I’ve been reading, in parallel, Fyodor Dostoevsky’s novel Crime and Punishment (excellently translated by Richard Pevear and Larissa Volokhonsky), which tells the story of Raskolnikov and which seeks to explain why he murders a pawn broker and what happens to him afterwards, and Norman Mailer’s documentary non-fiction book, The Executioner’s Song, which seeks to explain why Gary Gilmore shot two men in cold blood during a robbery in 1976 and what happened subsequently to him. Both are big books and I’m about half-way through both. Both are incredible and Dostoevsky’s influence on Mailer is palpable.

Finally, for light reading, in the evening, before I sleep, I’m reading In the Belly of the Beast, an anthology of letters written by Jack Henry Abbott to Mailer when he was writing The Executioner’s Song and which offers an amazing insight into the criminal mind.

Prof Nicholas Grene

If you haven’t read War and Peace, now is the time. Confined as you are to limited space, this book offers you expanses across the whole of Russia, much of Europe. The families and connections that criss-cross between the central figures of Pierre, Natasha and Andrei involve you in a complete, completely believable world. Short chapters keep you turning the pages, hook you in like a soap opera. You may have to skip some of Tolstoy’s lectures on the philosophy of history, but all the rest is compulsively readable. Go for the translation by Richard Peaver and Larissa Volokhonsky, if you can get it.

Prof Andy Murphy

My choice for perfect lockdown reading would be Jaroslav Hašek’s brilliant comic novel The Good Soldier Švejk. Švejk is a lowly private battling his way through World War I. He presents himself as being incredibly stupid, but we’re never entirely sure whether this isn’t, in fact, simply an act designed to help him cope with the absurd demands of army life. The book anticipates Joseph Heller’s Catch 22 in its poignant comedy. It helps remind us of the absurdity of life and the fact that our best protection in these times is humour and a sense of precious humanity.

Reporting by Martha Kirwan.