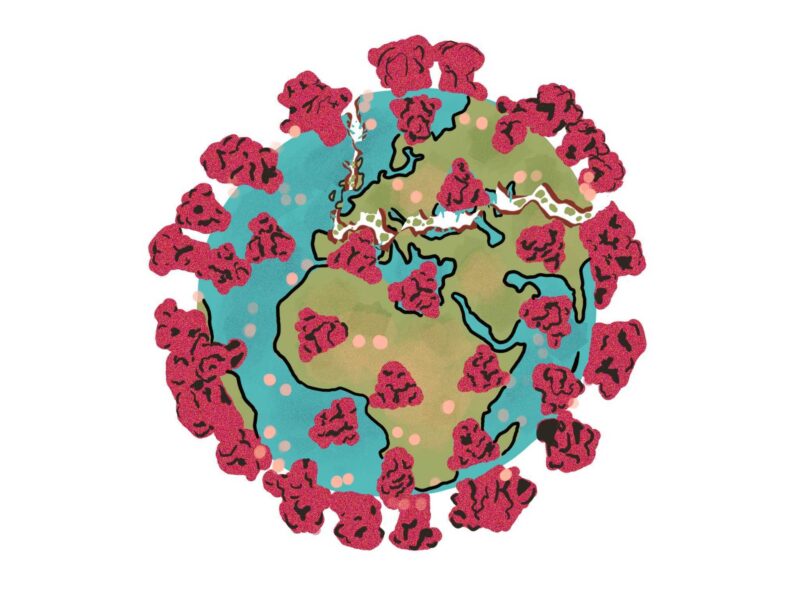

As the coronavirus hits hospitals, headlines and economies across the world, countries are beginning to implement draconian measures many believed were confined to the pages of an Orwellian novel.

Even in Germany, a country often seen as a champion of liberal democracy, citizens can be fined up to €10,000 for failing to comply with strict regulations. Italians, who have been in lockdown for over four weeks, now require a permit to leave their homes and, in Spain, similar measures have been extended until April 25th.

While most have their eye on the infection rate and death toll closer to home, we must not forget about the changes that are happening further afield – particularly in countries with a turbulent political past.

In Hungary, for example, the Prime Minister, Viktor Orbán, has recently passed legislation that allows him to rule by decree. Meanwhile, in Moscow, an app has been designed to monitor citizens and track their movements.

People are so focused on what’s going on with their health, understandably, that I am not sure we are awake to the wider, extremely sinister things that are happening

Given the current political climate, the tightening of authoritarian grip in the name of national safety, this may not come as a surprise. After all, the threat of populism and authoritarianism was becoming more prevalent long before social distancing and stock-piling became the new norm.

However, as Jane Ohlmeyer, director of the Trinity Long Room Hub, warns, “people are so focused on what’s going on with their health, understandably, that I am not sure we are awake to the wider, extremely sinister things that are happening”.

For some time now, Ohlmeyer, and other leading academics, have been wondering: “What is it in the world that is making populist and authoritarian approaches to government more attractive than democracy?”

This question finds itself at the heart of a new online curriculum launched by the Trinity Long Room Hub last week.

Over the past 18 months, Trinity – alongside Columbia University, University of São Paulo, Jawaharlal Nehru University and University of Zagreb – has worked on the Crisis of Democracy project, which explores the relationship between democracy and cultural trauma.

However, amid a global pandemic, the work of these institutions appears even more relevant now than it was 18 months ago. Ohlmeyer tells me that in “all countries, the situation is far worse today than was then and the threat to democracy is even more profound and even more real as we speak”.

In this sense, the new online curriculum – which was developed from the Crisis of Democracy project – could not have come at a more opportune time.

Speaking to The University Times, Bruce Shapiro, the executive director of the Dart Centre for Journalism and Trauma at Columbia University, says that it is “a genuinely global, transcontinental cross-cultural curriculum”.

Shapiro says the project – freely available worldwide – “resists the easy lure of borders, the easy lure of intellectual silos and the easy lure of narrowly defined dialogue”. Instead, he argues, it emerges as “a very important statement about the possibility of global inquiry and global intersectionality”.

Indeed, it is the degree of global intersectionality, as well as the arts and humanities perspective the curriculum offers, that makes it so unique. According to Rosemary Byrne, a professor of legal studies at NYU Abu Dhabi, the course brings together “a very genuinely international network of specialists”.

It was through the collaboration of these specialists – at a nine-day summer school organised by the Global Humanities Institute last July – that “the curriculum was really developed”, according to Ohlmeyer.

In fact, the structure of the curriculum offers people an opportunity to relive the experience of the institute’s participants. The online lectures and workshops – recorded over those nine days – offer people a unique arts and humanities perspective on the issues facing democracy today. Determined not to confine the discussion to the traditional areas of politics and economics, this course emphasises the role of cultural trauma in the crisis of democracy.

Despite having been developed 18 months ago, this living curriculum continues to pose questions that are very relevant to the current crisis we are experiencing. Although many are aware that the coronavirus pandemic is a global health emergency, according to Shapiro, it may also be considered “a crisis for democracy”.

If we are not talking in an active way about how we preserve and enhance democracy in this pandemic, then we’ll be in trouble

However, the prospects are not as bleak as they may appear. We may not have reached this point yet because, according to Byrne, a true “crisis of democracy” involves “the dismantling of structures that protect actually the democratic processes”. When it comes to the coronavirus, Shapiro says, it’s important to remember “that a crisis can go either way”.

Indeed, it is this fact – that a crisis can go either way – that makes this course so relevant. It stimulates thought and conversation during a period of democratic turmoil. It also allows us to heed Shapiro’s warning that “if we are not talking in an active way about how we preserve and enhance democracy in this pandemic, then we’ll be in trouble”.

Perhaps one of the most interesting aspects of the curriculum is that it offers perspectives from disciplines – arts, humanities and journalism – that often come under fire during the rise of authoritarianism. However, it does not victimise these fields, or label them as easy targets. Instead, it highlights their strength, power and resilience. As Shapiro points out: “The reality is that, at its best, journalism is a democratising force, and the bad guys know it.”

Barack Obama once claimed: “The arts and humanities aren’t just there to be consumed when we have a free moment. We need them like medicine.” In the current state of affairs, this certainly rings true. Shapiro insists that attacks on the press – the watchdogs of society – cannot simply be treated as “collateral damage to the rise of authoritarians. I think they are actually central”. Ohlmeyer remarks, in a similar vein, that arts and humanities often “make audible what later becomes visible”.

While nobody can be certain of the state of democracy in the wake of the coronavirus, Ohlmeyer says she hopes democracy will emerge “intact and strengthened, even” from current uncertainty. The new curriculum, she says, is a stepping stone.

She says that the project “shouldn’t just be for academics…we’d like it to go to the widest possible audiences.” She tells me of the growing necessity to “take these conversations beyond the walls of Trinity and beyond the walls of academia”.

Because after all, nobody is immune to the threat that authoritarianism poses, and the exacerbation that coronavirus may cause.