In Ulysses, James Joyce’s much-discussed modernist ode to Dublin, the writer suggests that a “good puzzle would be crossing Dublin without passing a pub”. Were he writing today, he might find similar puzzles in crossing the city without passing the decaying shell of a neglected building, or perhaps viewing a crane on the site of some redevelopment.

The closure of Dublin’s nightclubs and event spaces has become an increasingly disheartening source of discussion in recent years, but we might do well to place this narrative of decline within a longer tradition of Dublin failing to value its built environment.

Dublin’s visual identity has historically been contested. Closely tied to Britain by geography and colonial occupation, until the advent of independence much of the city’s architecture had been inherited from our neighbours. It can easily be argued that our rows of Georgian townhouses are essentially British in character, serving as an awkward reminder of an imperial centre imposing its ways of building across its empire.

In this sense, it is perhaps no surprise that Dublin’s built environment has often been dismissed as “un-Irish”. In a tradition beginning with the Irish Literary Revival and carried on into the Free State by De Valera, Irishness has frequently been defined in opposition to the city.

Instead, we were to look misty-eyed towards the mystical peasant emerging from their thatched-roof cottage to toil in the bog. Buildings only figured in this vision insofar as they were either a church or a pub. The prevalence of this anti-urban, anti-modern sentiment has left little space in our popular consciousness for Dublin’s buildings as part of our national heritage.

Where concrete stained the city before, glass and steel now proliferate

Donough Cahill, the executive director of the Irish Georgian Society, argues that this was not always so strongly the case. “The political association of the city’s architecture with colonial rule came more to the fore in the 1950s and 1960s, at a time when the city was developing economically and there was an aspiration for constructing in a new architectural idiom”, he says. “It wasn’t until then that there was considered to be justification for replacing an architecture of the past associated with colonial times.”

As part of Dublin’s economic boom in the 1960s, swathes of new investment entered the city, much of it from Canadian and American investors. Dublin became caught between a newfound embarrassment towards its Georgian legacy and a desire to rapidly modernise its built infrastructure. The effects of this were soon to become disastrous. In June 1963, Dublin experienced a particularly bad series of storms, which resulted in the collapse of two 18th century tenements within the space of a fortnight, claiming four lives. As a result, Dublin City Corporation introduced the 1963 Planning Act and the 1964 Local Government Act, which loosened regulations on the evacuation, demolition and redevelopment of Dublin’s Georgian tenements. Over 900 buildings were condemned in the 12 months following this legislation.

Of course, the need to rehouse people living in tenements unfit for purpose was paramount, but this was not the only reason for which the buildings were demolished. “As a consequence of the need to rehouse people, many of the buildings in use as tenements were deemed unstable and demolished”, Donough acknowledges, “though I think I would be right in saying that they weren’t always unstable. I also think I would be quite right in saying that there were plenty of buildings which were needlessly demolished, but perhaps to a certain degree it was a norm for the times. We didn’t have legislation in place to protect these buildings, and when this legislation was brought in during the late 1960s it was too late”.

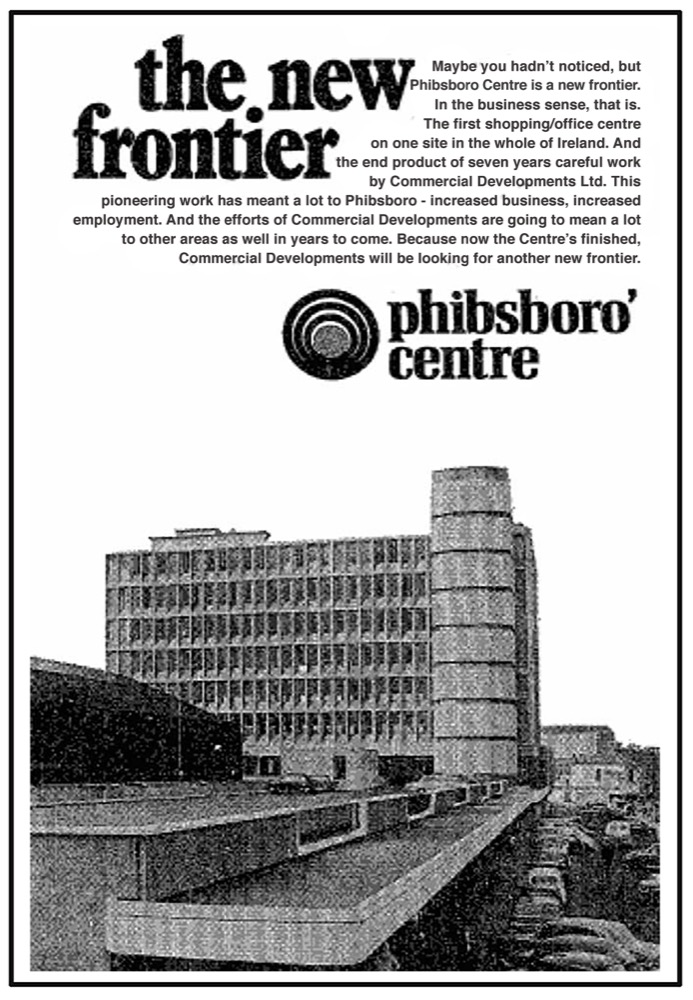

What was to replace them was left largely to the discretion of developers and their vested interests. The 1960s saw an unprecedented period of building, largely office blocks in the Brutalist style developing in Britain at the time. The bare-bones, raw concrete aesthetic of Brutalism appealed to the more cynical developers as it allowed them to produce buildings with little consideration towards visual appeal and yet market the look as a “new frontier”.

Artist and architectural historian Peter Pearson identifies this rapid development as representative of the zeitgeist from the 1960s through to the 1980s. “Demolition was just the mood of the time”, he says. “Everyone, from government bodies like An Post, Office of Public Works, Dublin City Corporation to hospitals, charities, churches, even Trinity – if they closed down they just knocked so they had a clean site to build a new office block on, simply due to commercial forces.” Pearson was instrumental in lobbying for the preservation and regeneration of many areas of Dublin that may have suffered the same fate. He notes how, in the 1980s, the council had planned to demolish much of Temple Bar in order to make way for a new bus station. “That was one of the areas we managed to save”, he said.

We must acknowledge, however, that for every cynical tower there was an earnest one too. Irish architects were engaged in the difficult task of creating an architecture modern enough to represent an increasingly prosperous Ireland and the hangover of rooting “Irishness” in something ancient. Modern architecture was doomed to fail in this battleground of identity – while it certainly represented a radical departure, it also did little to convince of its suitability for Ireland.

While Dublin’s concrete developments of the 1960s might fail to gain much admiration outside of circles of architectural purists, they also mark a definitive period in the city’s architectural legacy. Yet, despite their monumentality, we are beginning to see these structures disappear at an alarming rate. Ironically, the buildings that destroyed so much to accommodate their heavy footprint are experiencing the same fate as the Georgian and Victorian buildings they replaced.

The crucial difference is that these buildings are rarely more than 50 years old, barely given the chance to establish themselves as part of the city’s fabric – Dublin is eating itself much faster than before.

Fitzwilton House on the Grand Canal, one of Dublin’s more sincere and interesting attempts at Brutalist design, was demolished last year to make way for a new office development. The much-maligned Hawkins House (1962), which itself replaced the Theatre Royal, was brought down last year. Phibsborough Tower is earmarked for demolition, along with the former Bord Failté Building (1961) on Baggot Street. These are just to name the more significant examples.

Neglect is an issue which can’t be tackled through legislation

Much more common than demolition is a process called “active neglect”, where buildings are intentionally allowed to become run down and decrepit in order to justify their eventual redevelopment. Cahill notes that, unlike demolition – which can be prevented by placing buildings on the Council’s Record of Protected Structures – “neglect is an issue which can’t be tackled through legislation”.

This trend of neglect and destruction is underpinned by a new wave of economic growth in Dublin, as swathes of multinational corporations move their headquarters to the city at a rapid rate in order to take advantage of our low rates of corporate tax. A poignant example might be found in the 2018 demolition of the old AIB Headquarters in Ballsbridge (1969) to make way for Facebook’s new offices. Where concrete stained the city before, glass and steel now proliferate. Much of the redevelopment currently taking place in Dublin is in and around the Docklands area, which Google Maps now names as Dublin’s “Silicon Docks”. Easy as it is to dismiss the concrete structures being replaced, what do these new buildings contribute to the character of the city?

Developers’ renderings show us fanciful images of new structures replete with bushy green roofs and open “public” spaces, though it is worth noting that when budgets are overrun, these aspects are the first to be omitted. The models show buildings that are transparent and able to be looked through, creating a sense of openness and space, but it must be noted that glass has more of a habit of reflecting light than these might suggest.

The other type of building we are beginning to see springing up very quickly is the luxury student accommodation complex. On the outside of one such development, near the Five Lamps, is a sign that reads: “Blink and you’ll miss it! Super fast 21st century build.”

We know that the council fails to value Dublin’s cultural spaces, but this is arguably just a symptom of its failure to value Dublin’s spaces more broadly. Only three buildings built since 1945 have been added to the Council’s Record of Protected Structures, meaning many more demolitions are likely to follow. Dublin City Council and An Bord Pleanála continue to approve redevelopments and demolitions while failing to invest the proper time and resources in maintaining the historic building stock we already have in the city.

Showing me around his exhibition of architectural artifacts taken from buildings being demolished in the 1970s and 1980s, Pearson says that “people might ask why I am concerned with keeping these [artifacts]. They give Dublin its identity, and it’s one unique to Dublin, and once it’s gone, that’s it. You can’t retrieve it very easily”. Perhaps we ought to start giving our buildings the respect they deserve and avoid the need to “retrieve” this identity in the first place.