Over the course of the 20th century, the Irish state developed a track record of prioritising immediate political interests ahead of its desire to preserve the country’s heritage. In 1922, for instance, the provisional government’s infamous decision to shell the Four Courts in resulted in the explosion of the Public Records Office – and the hundreds of years of recorded Irish history stored inside it. In 1964, the Irish government decided to knock down 16 houses belonging to arguably the finest Georgian streetscape in the world – extending nearly one kilometre from the National Maternity Hospital to Lower Leeson Street – to build the new ESB headquarters.

Yet the decision to destroy the Wood Quay archaeological site in favour of building Dublin Corporation’s new headquarters could surely be considered the Irish state’s biggest failure in protecting its heritage.

From the beginning of the 20th century, Dublin Corporation (the modern-day City Council) believed that Wood Quay’s central location made it the ideal site for its new offices. Una MacConville, an archaeologist working on the site in the 1970s, says that there was an urgency about Dublin Corporation’s search for a new building at the time: “The Corporation were working in dreadful conditions all over the city, really appalling conditions.”

However, as the site at Wood Quay was prepared for construction – through demolition and excavation – archaeologists quickly came to the realisation that they were not simply dealing with the very heart of medieval Dublin. According to Caoimhe Whelan, the honorary secretary of the Friends of Medieval Dublin, archaeologists on the site saw that they were also being presented with “a really good window into what the medieval city was actually like” – an opportunity which was “incomparable in the European context”.

By 1100, when the wall was built by Muirchertach O Brian, it would have been one of the wonders of Ireland. And, in fact, it was described as such in a 12th century text

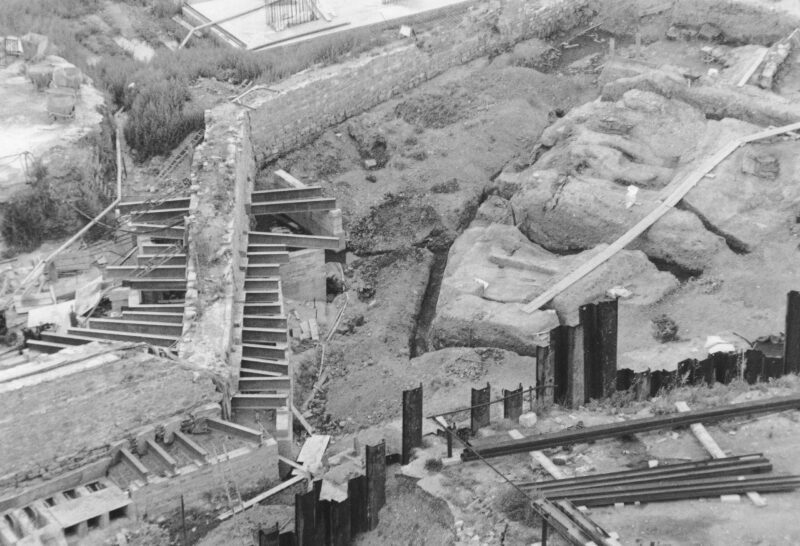

The anaerobic conditions in the earth at the site had allowed for the preservation of an abundance of wooden structures and artefacts. This meant that the near-complete foundations of around 150 Viking-age houses could be identified. The foundations were accompanied by benches, workshops, fences and paths. Roughly 100 metres of the 12th century city wall were also preserved – a very significant discovery according to Ruth Johnson, City Archaeologist for Dublin City Council.

“By 1100, when the wall was built by Muirchertach O Brian, it would have been one of the wonders of Ireland”, Johnson says. “And, in fact, it was described as such in a 12th century text.”

The findings spanned several centuries, from the first Viking settlement to the Norman city of the 12th to 14th centuries, making it near impossible for archaeologists to decide whether to sacrifice certain structures in order to unearth older ones beneath.

But the most difficult challenge archaeologists faced, from the commencement of work in 1974 to the end in 1981, was their race against the bulldozers. The timetable of the excavations changed several times, with limited extensions being granted as the importance of the site became clear to Dublin Corporation. MacConville recalls that: “You’d be given an extension of six weeks, so you’re operating to a six-week deadline and obviously you have a plan for that. But then at the last minute you might be told, well, you have another three weeks – and that’s very frustrating.”

Such a limited duration of time for excavations was a far cry from the years that archaeologists felt they needed to properly investigate the site. In fact, the excavations had to be carried out in such a rush that many historically relevant artefacts and structures were destroyed or removed before they could be examined. It was even reported that people who searched through Dublin Corporation’s dumps managed to collect museum-quality collections of artefacts. In one case, a brilliantly preserved viking sword was found in a dump after debris belonging to the site was deposited there.

Underneath the ground, anaerobic conditions in the earth had preserved a site including Viking-age houses, benches, workshops, fences and paths, giving archaeologists a glimpse into Dublin hundreds of years ago.

Another issue which arose during the excavations was the relationship between archaeologists and workers for John Paul Construction, the developer charged with building the offices. On many occasions, areas of the site were dug up without archaeologists being present or even before archaeologists had a chance to excavate them. According to Nick Maxwell, an archaeologist working at Wood Quay in the 1970s, tension between the different parties meant that “there was no respect, absolutely none”.

“In fact, there was a great deal of hostility from the developers, from the actual people on the site, and it’s hard to blame them because it was their livelihood, too”, he says.

Maxwell recalls an incident in January, 1979, when he and his colleague decided to take a stance: “The bulldozers were going to come in behind the city wall and remove one of the most important parts of the site… and the now professor Gabriel Cooney and myself one Saturday morning climbed the fence because we were locked out on the weekend and stood in front of the bulldozers and were actually led away by the guards.”

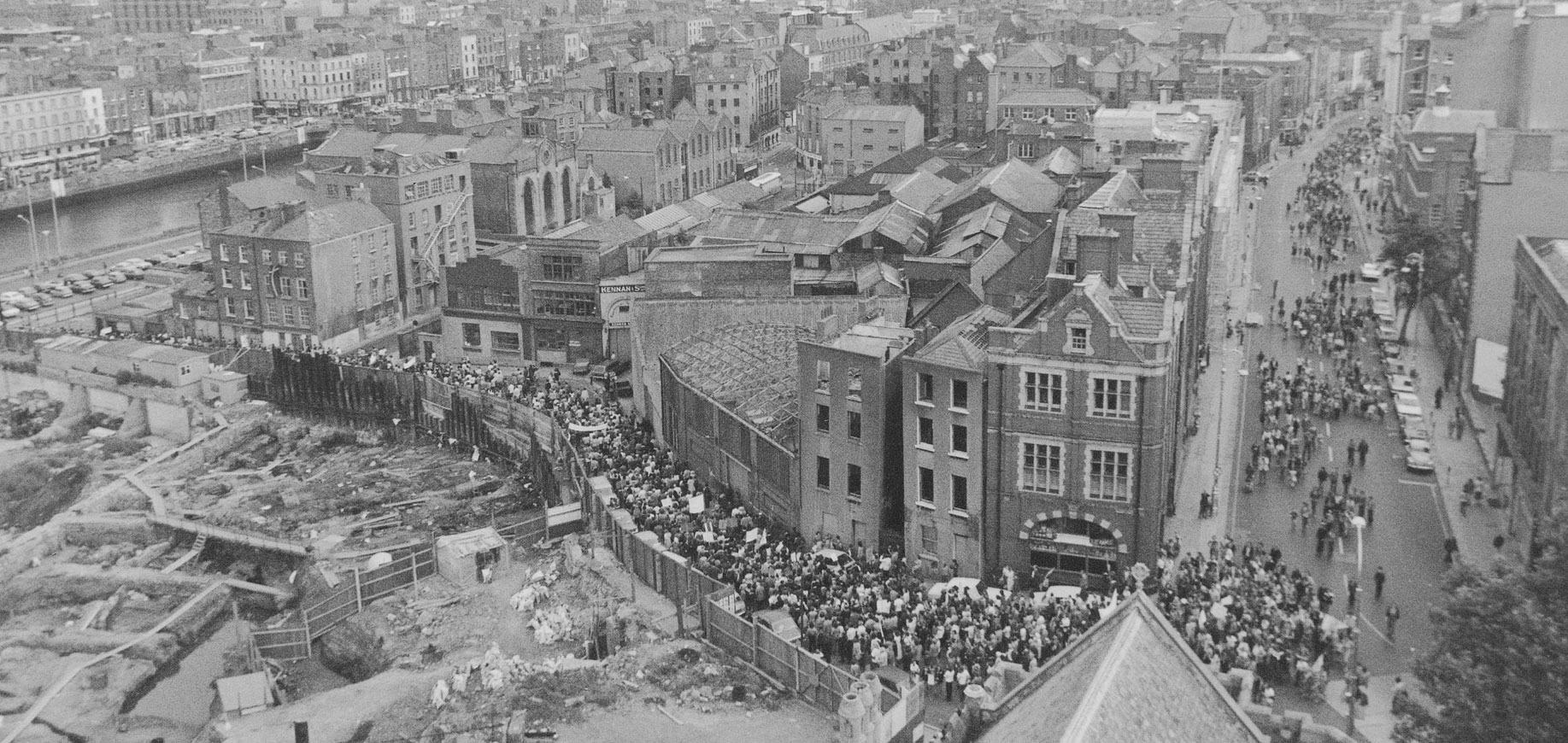

The blatant disregard for the archaeologists’ work and a growing will to preserve the site led to the creation of the “Save Wood Quay” campaign, which called for Dublin Corporation to find an alternative site for its offices. The campaign amassed around 200,000 handwritten signatures for its cause – which was no small feat in an age before social media. A march involving 20,000 participants, with representatives from many sectors of Irish society, filled the streets of Dublin on September 23rd, 1978, and helped the campaign gain momentum. The march was a colourful display of Viking costumes, wooden swords and even an improvised Viking boat on the Liffey.

Anngret Simms, a prominent historical geographer and Wood Quay campaigner in the 1970s, attended the marches. “I remember standing on a lorry next to Christchurch and looking down”, she says. “There were posters [from] people who had come up from Kerry, down from Donegal, people from all over Ireland. People just wanted their heritage. It was amazing.”

She says that Ireland’s joining the European Economic Community in 1973 was part of the reason that Irish people took Wood Quay to heart. During the period shortly after the country’s entry into the bloc, there was a will “to look beyond Ireland and think of people in Ireland as part of Europe” – and with this, the recognition of Wood Quay’s importance as a European site.

In fact, there was a great deal of hostility from the developers, from the actual people on the site, and it’s hard to blame them because it was their livelihood, too

In the same year, the voluntary group “Friends of Medieval Dublin”, led by its chairman Fr F.X. Martin, advocated for the designation of Wood Quay as a national monument. After considering expert archaeological evidence (in a court case led by the future president of Ireland, Mary Robinson), the High Court gave the area south of the old city wall such a classification in 1978. This ruling, according to Simms, caused considerable frustration for Dublin Corporation.

“They said to F.X. Martin and myself, ‘do you realise that if you go to court and you win, the John Paul construction people will then ask you to sell your private house and pay for the expenses that have occurred to their company?’. So they were threatening us all the time. I mean it was uncanny that they were prepared to do that”, Simms says.

In the meantime, letters highlighting Wood Quay’s European significance and a desire for its conservation arrived from archaeologists, professors, and directors of museums from at least seven European countries including – in a show of Viking solidarity – Norway, Denmark and Sweden. The Council of Europe, a human rights organisation representing over 20 European countries, added its voice to the mix in 1979.

The question of whether preserving the site was ever a truly viable option produces diverging answers to this day. Maxwell believes that preserving the entire site was never realistic.

“The whole site was completely waterlogged. In those kinds of anaerobic conditions things like wood and so on are preserved intact but once they are dried out they just go to dust”, he says.

The counterargument is that if Dublin Corporation had looked to Scandinavian countries, it would have seen new techniques of conservation that had been successfully applied. As Simms puts it: “Oh yes, the Danes have preserved whole boats – it wasn’t a question of technology or how to preserve, it was a question that they wanted space for the offices.”

The final blow to the site came in 1979 when John Paul Construction appealed the High Court’s National Monument decision. Simms tells me: “The Supreme Court got quite nasty and said F.X. Martin was misleading the youth of Ireland, and they dismissed the whole thing and they made F.X. Martin responsible for the expense of breaking the contract with John Paul.”

Dublin Corporation was desperate to find a headquarters, and felt Wood Quay was the perfect spot.

Shortly afterwards, Dublin Corporation struck a deal with the Department of Finance, using a loophole in the outdated 1930 national monument legislation, which allowed it to remove the historic artefacts from the site and give construction the go-ahead.

This move motivated the Friends of Medieval Dublin to launch Operation Sitric (named after the Norse King of Dublin, Sitric Silkenbeard) in order to halt the bulldozing in June, 1979. 52 people, including writers, politicians, trade unionists, sculptors, archaeologists and concerned citizens, participated in a three-week takeover of the site. During this time, the protesters had to put up with angry construction workers who, at one point, dropped gallons of water on them, ruining their sleeping bags.

But this impassioned display of affection towards the site did not sway Dublin Corporation. Simms recalls that on June 21st, “the message came from the courts that the people who were occupying the site would be arrested and put in jail.”

Furthermore, while Dublin Corporation had planned to retain the wall in its entirety, the developer John Paul actually dismantled most of it with a view to reconstructing it upon the completion of the building. But, Johnson tells me, this was not possible. “We’ve looked at the feasibility of reconstructing parts of that wall, but unfortunately it doesn’t seem to be in a system that was designed by conservation experts. It’s instead something that was ad-hoced on by the developer.”

The directors of the National Museum, the body responsible for “preserving and presenting the stories of Ireland”, also had a role to play in the destruction of the site. Instead of pushing for more time and resources to carry out efficient excavations, they were content with respecting the timeframes set out by Dublin Corporation. This was probably a consequence of the National Museum having to raise its own funds in the early years of the excavations, and MacConville concedes: “I do think that they have to be given some degree of credit for allocating members of their staff when they didn’t have a huge amount of staff.”

Even so, it is evident that successive directors lacked an appreciation of the site. Joseph Raftery, the director of the National Museum between 1976 and 1979, disagreed in 1979 with the High Court’s decision to declare Wood Quay a national monument.

Archaeologists were in a race against the bulldozers to unearth some of Dublin’s best-kept secrets.

Maxwell believes the museum may have been too clouded by nationalism at the time to properly appreciate the findings. “We were looking at the immediate post-Norman period, so why would we want to look at that, you know, we want to get rid of the English, we don’t want them here messing up our museums”, he explains.

Interestingly, Raftery’s statement came shortly after his mandate was extended not once, but twice. His own staff were perplexed by this decision and contacted the Minister of Education for an explanation. They were told that Raftery “was retained in the public interest, particularly in relation to the Wood Quay issue” – suggesting that he had been kept on because his opinion corresponded to that of Dublin Corporation.

Simms believes that the National Museum was indeed trying to please Dublin Corporation: “All those people at the top worked into each other’s hands, they did things secretly.”

Despite these setbacks, Simms believes that the campaign made an impact on Dublin Corporation. “The people of Ireland made their views known and they actually managed to get eight more years of excavation than Dublin Corporation had originally envisaged”, she says.

Indeed, one last extension to the excavations was secured, continuing until March, 1981. Five years later, after the archaeology on the site had either been removed or destroyed, the offices were built.

Frustratingly, within seven years, Dublin Corporation had changed its tune and was publicly embracing the site’s historical importance. In 1988, during Dublin’s millennium celebrations, the Lord Mayor awarded the first of the “Millennium Medals” to those who fought to save Wood Quay. One of those who received the medal was F.X. Martin. On that very same day, further highlighting its about-face, Dublin Corporation stopped seeking compensation from Fr Martin for the hold-up to work during his Supreme and High Court injunctions.

While Johnson concedes that “there was undoubtedly a lot of pressure on the archaeologists” during the excavations, she points out that we should not judge the excavations by the standards of our times.

“Everything was very new, urban archaeology was a new thing in the 60s and 70s. It was in its infancy, really. Rescue excavation as well was fairly new, these huge developments requiring archaeological excavation in advance”, she says.

Moreover, since the 1970s, Dublin City Council has made significant progress in its handling of Dublin’s heritage. Johnson points out that it “has two archaeologists working full time, which wasn’t the case up until even 3 years ago – I was on my own here or with temporary assistants.”

Everything was very new, urban archaeology was a new thing in the 60s and 70s. It was in its infancy, really. Rescue excavation as well was fairly new, these huge developments requiring archaeological excavation in advance

Dublin City Council has also hired a Heritage Officer and introduced planning requirements which allow archaeologists to investigate sites in the city before development. Today, it honours Wood Quay’s legacy through the Wood Quay Oral History Project, which aims to record the experiences of those involved in the Wood Quay saga.

Regretfully, it seems that the site’s full potential has yet to be explored. The excavation reports that outline the archaeological finds have only been partially published and have been inaccessible to academics for years – this means that the European research community is still waiting on a full report of the site. Simms says that one of the reasons for the delay involves another stand-off. “There’s a tension between the Royal Irish Academy and the National Museum. You see, it’s the same thing as before: the people at the top are just doing their best to play difficult and I just can’t understand it.”

The destruction of Wood Quay represents a national tragedy. Not only did it deprive Dublin of a national monument, but it also prevented subsequent generations of Irish people from gaining an understanding of their own medieval history that citizens of other countries possess. While countries such as France and Italy can turn to numerous surviving structures for inspiration, Irish people are limited largely to textbooks and re-creations.

But the fight to preserve Ireland’s heritage is by no means finished. Taking example from the public outcry over Wood Quay’s destruction, Irish people can fight to preserve the heritage that still stands today. As Whelan puts it: “We need to make sure that the next generation are aware of the value of protesting for heritage, it’s actually important to do that too. If people see Neolithic tombs being vandalised in Sligo, it’s important that they actually do or say something.”