The striking images of a beheaded Christopher Columbus statue in Boston and the dramatic toppling of 17th-century slave trader Edward Colston in Bristol are ones that we have, over this past year, become familiar with. In the wake of George Floyd’s death, a debate about the extent to which the names of our institutions and statutes can be regarded as symbols – of history, ideals, norms – is sensitive and enduring.

Public art is rarely considered educational. The function of memorials and statues is to select, affirm and potentially glorify individuals. But the presence – or replacement – of those statutes has symbolic potential.

The racial reckoning that colleges and universities across the globe are undertaking has not stopped in Ireland, nor at Trinity. In fact, the College Green entrance was built with money from tobacco duty, likely generated by slaves.

Ireland proclaims itself proudly as multicultural and inclusive, but exceptionalism and pervasive nationalist sentiment have deterred progress. The proposition that our institutions and revered historical figures benefited from British colonialism appears antithetical to our national identity. But in the process of examining the discrimination embedded in our society, we cannot overlook those aspects of our history that don’t affirm our sense of national identity – and especially those that threaten it.

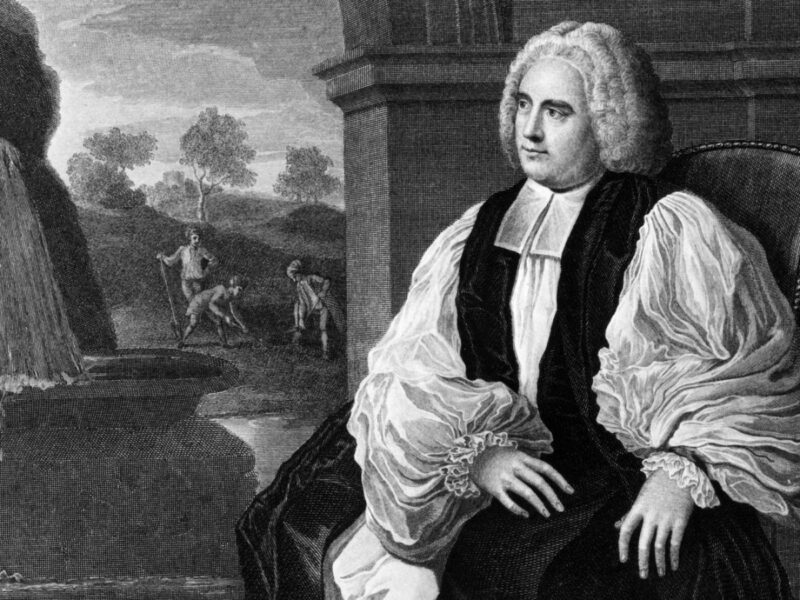

His views about slavery and his practice of slavery and his attitude towards class are relevant to understanding those works, but Berkeley is not famous for ethics or political philosophy. Those works are very obscure and very rarely studied

Dr Kenneth Pearce, Ussher Assistant Professor in Philosophy in Trinity, explains that Berkeley’s relative detachment from issues of race and ethics in his published work may have been a factor in the absence of live scrutiny about Berkeley’s past. “Berkeley wrote about ethics and political philosophy. His views about slavery and his practice of slavery and his attitude towards class are relevant to understanding those works, but Berkeley is not famous for ethics or political philosophy. Those works are very obscure and very rarely studied.”

What is understood, however, is Berkeley’s continued belief in the support of hierarchies. Pearce tells me that Berkeley “doesn’t have to say that Africans are inherently intellectually or morally inferior in order to justify slavery within his worldview… Berkeley can acknowledge that these people are spiritual, moral and intellectual equals without having to treat them any differently.”

Pearce explains that Berkeley could not contemplate “autonomy or the ability to make your own life decisions and control your own life as an inherently good thing that has to be a part of any good human life… that’s what he thinks is the role of these dominant groups with regard to subordinate groups: that they should be controlling always for their own good.”

What is striking about Berkeley, according to Pearce, is his ability to maintain his beliefs about the rigidity of class roles and even use them to justify further polarisation between the ascendant Anglican upper class, and the “other”.

Yale University named one of its residential colleges Berkeley College, in recognition of the philosopher’s contributions to the universities.

In his proposal to establish a college in Bermuda to educate Native Americans, Berkeley demonstrated this belief system. According to Pearce, however, “his project for benefiting those people cannot be separated from the project of keeping them in their subordinate positions, and this applies to African people, to Native Americans and also to the native Irish people”.

Although Berkeley believed Native Americans children were capable of learning subjects like history, medicine, maths and astronomy, in his published proposal Berkeley wrote of forcing, even kidnapping Native Americans, to live on the remote island: “[The students] could be procured either by peaceable methods from those savage nations, which border on our colonies, and are in friendship with us, or by taking captive the children of our enemies”.

Travis Glasson, an associate professor of History at Temple University, says that the Bermuda Project written by Berkeley astonishingly “validated slavery.” Glasson tells me that in the project Berkeley went so far as to “include the idea that enslaved children could become future missionaries. In the Bermuda project, slavery was envisioned as a possible tool for the promotion of Christianity.”

For Simon Kow, early modern studies director at the University of King’s College, attention should be drawn to the reasons particular historical figures are memorialised. In the case of Berkeley College, California, interest was focused on his views about America: “[I]s a philosopher who thinks that there is spiritual redemption to be found in America also going to be implicated in some way in the slave trade? That was clearly the case with Berkeley, at least with his ownership of slaves…[and] related to that, is the idea that his religiously motivated philosophy was meant to combat and refute aspects of modern philosophy which he thought were leading Europe into corruption.”

The process of untangling Berkeley’s philosophical and epistemological connections to slavery might pose a difficult problem. But what remains clear is that simplifying those connections or dismissing them as typical for an Enlightenment-era philosopher would be lacking nuanced. Glasson explains that in Berkeley’s writings “not just acceptance of but willingness to use slavery is integrated into the way that he thought about his society and more generally the human condition”.

In the Bermuda project, slavery was envisioned as a possible tool for the promotion of Christianity

Berkeley purchased four documented slaves to work on his plantation on Rhode Island, baptised Edward, Philip, Anthony and Agnes. A substantial part of the donation Berkeley endowed to Yale to fund the first scholarships there came from profits generated from his plantation. Pearce explains: “[W]e do not really have any evidence of how he treated his own slaves other than [that] they were baptised.” Notwithstanding his condemnation of the mistreatment of slaves and his advocacy for their education, there is no independent evidence about the lives led by the enslaved people Berkeley owned.

Berkeley’s role in the propagation of his views on the Christianisation of slaves emerged clearly during what is known as his Anniversary Sermon. Here he implicitly discussed the Yorke-Talbot Opinion, written by Attorney General Sir Philip Yorke and Solicitor General Charles Talbot, which stated that the baptism of slavery was not grounds for their emancipation. It was used to appease and give authority to slave owners and masters, and concurrently bolster the agenda of missionary Anglicanism.

Pearce explains: “[Berkeley] refers to the Yorke-Talbot Opinion, not by name but he alludes to it in that speech and he takes credit or partial credit for securing that opinion.”

The tangible impact of Berkeley’s soliciting of this opinion, Dr Peter West, Adjunct Assistant Lecturer in Philosophy at Trinity explains, is that “for decades afterwards pro-slavery thinkers had something to point to which said in law that they’re not free just because they’ve been baptised”. Although the Yorke-Talbot was merely an opinion and not a judicial statement, its legitimacy afforded the opinion a similar effect.

The question remains whether two conflicting perceptions of Berkeley can remain intact: can his contributions to philosophy and epistemology be celebrated, and his ownership of slaves be condemned simultaneously?

not just acceptance of but willingness to use slavery is integrated into the way that he thought about his society and more generally the human condition

Clare Moriarty, an Irish Research Council postdoctoral fellow in Trinity, says: “I think it’s important that the university as an institution take a look at what kind of people we want to lionize (or continue to lionize) by having our buildings and statues named after them. Because there is a big difference between statues and buildings (which are not educational devices, contrary to some views) and a place on the educational curriculum.”

We need more than alacrity in learning about Berkley’s ties to slavery, which are threefold: his ownership of slaves, the integration of slavery into his Bermuda project and his influence in the publishment of the Yorke-Talbot Opinion. Although Berkeley did not give racism and colonialism the intellectual authority that philosophers such as Hume or Kant did, his missionary transgressions and the intolerance of his worldview mean that not only did he uphold the systems of racial oppression, but that he also played an active role in ensuring their endurance.

The extent as to which Berkeley’s slave-owning can be considered marginal to his philosophical contributions remains an issue. Whether the movement of renaming institutions and toppling statutes is shortsighted is relevant too. Renaming the Berkeley library may not be a fixed solution but critical engagement with Enlightenment figures and our complicit institutions could be helpful first steps.