“We will never forgive until the end of the world,

All the records written with our blood,

Revolution,

Those who died in the fight for democracy,

Oh – dear heroes,

A nation of many heroes.”

This is a rough English translation of the song, “Until the End of the World”, by Daw Soe Moe Lwin. It is the anthem of revolution that commemorates the thousands of deaths, mostly students, in the 1988 pro-democracy uprisings against the military regime in Myanmar. This song is now hailed again as the song of the 2021 Myanmar Democracy Revolution.

Myanmar is a country gripped by decades of military rule, from the first military coup in 1962 and a history of brutal crackdowns, leading to an estimated 3,000 to 10,000 deaths in the 1988 uprisings and the deaths of hundreds of monks and nuns in the Saffron Revolution. It has only come onto the global scene in the last 10 years, when the country finally opened up after it transitioned to a semi-democracy from the first elections in 2010, where the military-backed party Union Solidarity and Development Party USDP won, and the second more democratic and free elections in 2015, where DawAung San Suu Kyi’s National League for Democracy won with Daw Aung San Suu Kyi taking her role in the country’s political scene as State Counsellor of Myanmar.

The country’s economy has been crippled by broad sanctions placed upon it during the years of military dictatorship, with rising poverty and lowered standards of living during the years of military rule. Access to the world through the Internet was only available in recent years, but in my generation specifically access was more available, allowing Gen Z to grow up being able to express themselves more freely. Even so, there was always the risk of detainment, an underlying fear of the military. When you speak up about politics in Myanmar, you feel the need to look over your shoulder, lest an intelligence agent listens in.

When the University Philosophical Society, a society I am part of, organized a debate on the motion, “This House Has No Confidence in the Government” and student speakers openly criticized the Irish government, I was struck by the sheer freedom of speech displayed in Ireland. I come from a country in which students run not the risk of expulsion, but repercussions in the form of detainment or being taken away in the silence of the night, should you speak anything remotely negative about the military government. Even writing this article is a privilege granted to me, studying abroad, that is not granted to my fellow Burmese citizens in Myanmar.

Access to the world through the Internet was only available in recent years, but in my generation specifically access was more available, allowing Gen Z to grow up being able to express themselves more freely

Ireland is a country whose youths have always been politically active, with droves of secondary school students and my fellow Trinity students leading the climate protests, college students raising petitions to repeal the eighth amendment and more. Similarly, Myanmar’s fight for democracy has always been led by youth movements, going so far as to pre-colonial days, when the founding father of modern Burma, Aung San, was politically active in his college days and head of All-Burma Students-Union. The 1988 revolution was headed by students of the Rangoon Institute of Technology, RIT. The main difference is that Myanmar’s students had been gunned down and silenced in the past revolutions, but this does not mean that we have stopped fighting. In fact, it has had quite the opposite effect.

The military staged a coup on February 1st, detaining the State Counsellor Daw Aung San Suu Kyi and the President U Win Myint as well as senior government officials, on the day the new government was supposed to convene in Parliament. This was the government that was democratically elected in the 2020 November elections. As a result, the resistance movement saw a surge of student activists taking charge, both online and in marches. The military employed internet shutdowns as a means to cut off Myanmar’s contact with the world. This effort went without success, however, for they forget the huge number of Burmese diaspora studying abroad, who have grown up under the legacy of student leaders in the past, and who started spreading awareness, as well as the tech-savvy youths on the ground, who found ways to work around the Internet restrictions.

The restriction of Facebook and Messenger, the two main widely used platforms in Myanmar, led to an upsurge in the usage of Twitter among Burmese citizens and when that was also restricted, the country saw a 4,300 per cent increase in the usage of Virtual Private Networks or VPNs. Even so, there is an internet shutdown from 1am to 9am every single night for the past two weeks but protesters and activists take to updating the world about what had transpired every night as soon as the Internet lockdown lifts. The more the Commander-in-Chief Min Aung Hlaing tried to shut Myanmar off from the world, the more determined Burmese people became in getting their message across, and their voices heard.

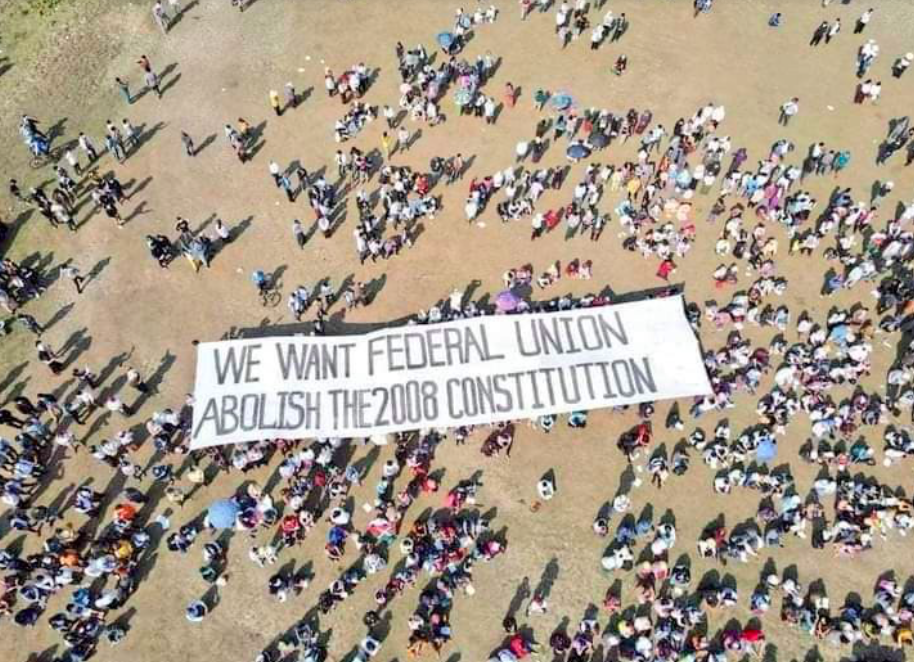

Scenes from protests in ethnic states in Myanmar.

The Civil Disobedience Movement was started by healthcare workers on the 3rd of February and has been one of the defining movements of the revolution. Civil workers refused to go to work under the military regime, including over 17,000 workers from over 1,200 government sectors across the country, composed of lawyers, teachers, electrical grid workers and more. Fundraisers have been set up by people around the world and in the country to support the civil workers and their families, led by Burmese college students studying abroad. This widespread movement has successfully paralyzed the government, for society is no longer able to function. In addition, private banks have shut down and the people of Myanmar are destabilizing financial institutions at the risk of a financial crisis, in what is already a flailing economy, to prove to the world they will not be ruled by the military again.

The youth movement in Myanmar is the latest to add to the youth movements in Asia fighting for democracy, effectively joining what is known as the Milk Tea Alliance – a movement started by the students in Thailand, Hong Kong and Taiwan in their battles against their respective dictatorial governments. The different ways in which milk tea is prepared give the Milk Tea Alliance its name. In Thailand, a food dye gives it its bright color. In Hong Kong, a tea dust and black tea combination gives it its extra potency. In Taiwan, tapioca pearls gave birth to the signature bubble tea. In Myanmar, the laphet yay in the different combinations of black tea, evaporated milk and condensed milk with its various names are ordered daily by the masses.

This pan-Asian solidarity is extremely important in proving to authoritarian regimes that democracy is not an exclusively Western concept that cannot be embraced in Asia (which they have been preaching in their decades of rigid control over countries to excuse their behavior) but that it is a universal concept, much like the freedom to vote, the freedom of speech and the freedom of expression.

In addition, Myanmar has taken note of the different ways in which Hong Kong protesters have adapted to the crackdowns and protected themselves. When the Myanmar armed forces brought out water cannons and tear gas in the first few crackdowns in the capital Naypyidaw and other major cities, protesters responded by wearing helmets and taking other protective measures demonstrated by Hong Kong youths.

Flowers in remembrance of Ma Mya Thwet Thwet Khine, a student who passed away in the fight for democracy.

General Ne Win, the first military dictator that staged a coup in 1962, said chillingly in 1988 that “when the army shoots, it shoots to kill. It does not shoot into the air”. This same sentiment has been shared by the military in 2021, with the rising death count due to headshots. Crackdowns in Myanmar have gotten more brutal as the weeks of peaceful protests go on with the increased use of live ammunition and the implementation of martial law, a curfew enforced from 8pm until morning. It was during this time that civil workers partaking in CDM and protesters were detained. Mya Thwet Thwet Khine, a 19-year old college student, was shot in the head in Naypyitaw the capital of Myanmar, and has since passed away. The military denied any responsibility, despite the circulation of footage of the shooting, perpetrated by a police officer, while the young student was hiding from the crackdown.

A crackdown in Mandalay, the second most populous city in Myanmar, on February 20th resulted in an estimated number of 50 people shot, 35 in critical condition and 7 dead. Footage of the shootings have surfaced online, one being pictures and videos of the shooting of a 16-year-old medical volunteer, Wai Yan Tun, who had rushed to help the protesters when the crackdown began. Western media has reported deaths to be “at least two”, and numbers circulating in Myanmar range from eight to 16. The reality is that we will never know the true death count as the military carts off hurt civilians, with the public not knowing what had become of them and the intent to make civilians disappear made clear. The accurate number of the people we have lost so far, we will never know, and that is the most devastating fact of the revolution.

On March 3rd alone, the number of reported deaths was 52, from Hpakant to Monywar to Mandalay to Yangon, the highest number of casualties in one day since February 1st, the youngest victim being 14 years of age. On March 1st, the number of deaths was close to 38 with 26 confirmed deaths on February 28th alone.

Even so, this has not deterred millions of people from going out into the streets in defiance against the military regime. The Burma Spring Revolution, taking place on February 22nd (known also as the 22222 Protests) saw an estimate of over 20 million people all across the nation, over 40 per cent of the population, in marches shouting for the release of Myanmar’s unlawfully detained political leaders, for a complete democratic federal union.

General Ne Win, the first military dictator that staged a coup in 1962, said chillingly in 1988 that ‘when the army shoots, it shoots to kill. It does not shoot into the air’

On the morning of the February 22nd, I anxiously messaged my 20-year-old friends, who would be marching that day, to write their blood types and emergency numbers on their arms in case of a crackdown. They knew the risk they were taking by participating in the nationwide protests and yet they went anyway, for they understood, in the words of Ko Min Ko Naing, a prominent pro-democracy activist, that there is nothing scarier than losing this fight (against the military regime), and therefore, there is nothing else to fear.

This is no longer a political crisis, but a humanitarian crisis in which we worry about the deaths and detainments of our loved ones and of our countrymen. As it stands, there are 748 people detained including activists, civilians, members of the National League for Democracy, members of the Union Electoral Committee – the same ones who did not find any evidence of electoral fraud, the reasoning behind the coup – outspoken actors and more, with active persecution of 686 individuals. This is not an internal affair, this is not a cabinet reshuffle, as some countries have labelled it as such. The crisis in Myanmar is a violation of human rights of the most acute kind, a threat to democracy and in addition, this crisis is happening on top of other crises in the country.

As it stands on the 3rd of March, the number of people arrested, charged or sentenced have climbed to 1498 since February 1st.

Myanmar is a country with over 130 ethnic groups and since the founding of independent Burma, oppression and exploitation of the ethnic people by the military has taken place, as well as the villainization of ethnic armed groups by the military labelling them as “rebellious insurgents” when in truth, they had taken arms to protect their land and their people. Religious and racial discrimination runs rampant in the country (as is seen in the Rohingya genocide of 2017 to which most of the country turned a blind eye to at the time). However, the entire country has come together and emerged united in this fight for freedom from the military, once and for all.

The majority Bamar Buddhists in the country now see what ethnic groups have had to endure under military rule (for the people of the ethnic states were always under threat of violence from the military even during the 10 years of semi-democracy before the coup), and we (for I am a Bamar Buddhist as well) have come to a reckoning. We will fight together, in unity. It is democratization we demand for now, no longer Burmanization, in which the country is ruled by the majority Bamars.

We see an emergence of youths expressing their sympathy and extending their apologies for not speaking up for the Rohingyas, for the Kachins, for the Karens, during the past month of the revolution and most prominently, we see ethnic groups banding together and peacefully protesting with us, despite us not having fought for them in the past.

Water cannons are being used against the peaceful protesters.

What Min Aung Hlaing did not anticipate was how his reign of terror would unite all of us, and how much strength there is within us to stand for and with each other. This is no longer a fight to return to the status quo, to the power-sharing before where the military still holds a veto power in parliament. This is a fight for a true federal democratic union, inclusive of all ethnic groups. We now call for an abolishment of the 2008 Constitution that was drafted by the military that has given it an automatic 25 per cent of parliament seats (only one of the many problematic clauses of the constitution). This is a revolution that has transcended all ethno-religious lines that the military has enforced on Myanmar for decades. United, we are standing, stronger than ever.

I was raised amongst extended family who had been active in their anti-military sentiments, from some of my family members participating in the 1988 marches, but my immediate family is of military background. Therefore, I grew up in a juxtaposition of military propaganda in a privileged military-provided household whilst also being told stories of student revolutionaries and the grievances the military has inflicted on the population of Myanmar when I went to my extended family’s home.

I grew up in an atmosphere where half of my environment was centered on visits to military generals’ households on the weekdays to try to curry favour and for young me to show off my literacy in English (which is a skill highly prided in Myanmar as it indicates that I could go abroad for tertiary education, and a Western education is highly coveted) and the other half was spent on weekends asking my uncles about how they escaped bullets while they were college students fighting in the failed revolution against the military regime in 1988.

This upbringing was unusual, for it instilled in me values that I would not have gotten if I had been in a purely military household. It instilled in me a sense of perspective of the affairs in my country that was not tainted by military propaganda, which was rampant at the time of my upbringing.

I may not have been able to see my privilege when I was younger, but I see it clearly now and the only way for me to move forward is by acknowledging my privilege and using it to empower those who did not, and still do not, have the luxury I had growing up, and to ensure that the circumstances surrounding the extreme inequality of life opportunities do not continue to exist. I cannot change the circumstances of my privileged upbringing but I choose where I stand now. When Myanmar is on the cusp of breaking free once and for all, from the grips of military rule, I choose to stand on the right side of history.

Being in Ireland, a democratic country in which freedom of speech and freedom of expression are not criminalized, but celebrated, has given me the hope that my country will also regain those basic human rights. This is a fight that Myanmar is fighting, with all the power its citizens can muster up. However, we need international solidarity. We need governments around the world to hear the voice of Myanmar, to not recognize the military government as legitimate, to enforce targeted sanctions on military-owned companies and for international companies not to do business with them for the economic gains fed into the military’s pockets allowing the military its financial autonomy to keep inflicting harm on the citizens of Myanmar. We need the world to work in coalition to enforce a global arms embargo on the military.

On the morning of the February 22nd, I anxiously messaged my 20-year-old friends, who would be marching that day, to write their blood types and emergency numbers on their arms in case of a crackdown

Most importantly, for anyone reading this who is not Burmese, we need you to keep caring about Myanmar. It is in no means a perfect country, but its people are kind, caring, loving and united, and they deserve the freedom and liberty that they have been deprived of for years. It is a country in which shopkeepers, whose businesses had taken hits since the pandemic, give away food freely to the protesters. It is a country in which people bang pots and pans (a Burmese tradition that is said to drive away evil) in unison at 8pm every single night, first as a sign of protest and then later as the military started arresting people during curfew, the same sound transformed into an alert for the whole neighbourhood to come to the house of the person the military is trying to detain, to protect them.

The people of Myanmar will prevail. Everything rests on this – our livelihoods, our futures and the generations that follow after us. We will be the last generation to witness a military coup. People of Ireland, people around the world, I urge you to extend your hand in solidarity with us, to stand with us. I urge you to hear the voices of 54 million Burmese citizens chanting, “Down with the military regime! The revolution must succeed!”

Editor’s Note (August 1st, 2021): This article was initially published anonymously as the author feared for the safety of her family if she spoke out against the military regime in Myanmar. However, she has since asked for her byline to be added.

Generally, the publication of articles written by anonymous authors is forbidden at The University Times. In certain cases, the Editor may make an exception if the publication of an anonymous article is of great public interest, and there is a significant risk that the writer may experience great harm as a result of their name being associated with the article, and where it is not possible for another person to write the piece.